Innate immune system

The epithelial surfaces form a physical barrier that is impermeable to most infectious agents, acting as the first line of defense against invading organisms.

[3] Desquamation (shedding) of skin epithelium also helps remove bacteria and other infectious agents that have adhered to the epithelial surface.

Lack of blood vessels, the inability of the epidermis to retain moisture, and the presence of sebaceous glands in the dermis, produces an environment unsuitable for the survival of microbes.

At the onset of an infection, burn, or other injuries, these cells undergo activation (one of their PRRs recognizes a PAMP) and release inflammatory mediators, like cytokines and chemokines, which are responsible for the clinical signs of inflammation.

PRR activation and its cellular consequences have been well-characterized as methods of inflammatory cell death, which include pyroptosis, necroptosis, and PANoptosis.

Chemical factors produced during inflammation (histamine, bradykinin, serotonin, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins) sensitize pain receptors, cause local vasodilation of the blood vessels, and attract phagocytes, especially neutrophils.

[5] Neutrophils then trigger other parts of the immune system by releasing factors that summon additional leukocytes and lymphocytes.

[5] When activated, mast cells rapidly release characteristic granules, rich in histamine and heparin, along with various hormonal mediators and chemokines, or chemotactic cytokines into the environment.

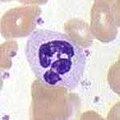

In general, phagocytes patrol the body searching for pathogens, but are also able to react to a group of highly specialized molecular signals produced by other cells, called cytokines.

[2] The binding of bacterial molecules to receptors on the surface of a macrophage triggers it to engulf and destroy the bacteria through the generation of a "respiratory burst", causing the release of reactive oxygen species.

The main products of the neutrophil respiratory burst are strong oxidizing agents including hydrogen peroxide, free oxygen radicals and hypochlorite.

Neutrophils are the most abundant type of phagocyte, normally representing 50–60% of the total circulating leukocytes, and are usually the first cells to arrive at the site of an infection.

Dendritic cells are very important in the process of antigen presentation, and serve as a link between the innate and adaptive immune systems.

When activated by a pathogen encounter, histamine-releasing basophils are important in the defense against parasites and play a role in allergic reactions, such as asthma.

γδ T cells may be considered a component of adaptive immunity in that they rearrange TCR genes to produce junctional diversity and develop a memory phenotype.

Some products of the coagulation system can contribute to non-specific defenses via their ability to increase vascular permeability and act as chemotactic agents for phagocytic cells.

For example, beta-lysine, a protein produced by platelets during coagulation, can cause lysis of many Gram-positive bacteria by acting as a cationic detergent.

[3] The innate immune response to infectious and sterile injury is modulated by neural circuits that control cytokine production period.

Innate immune system cells prevent free growth of microorganisms within the body, but many pathogens have evolved mechanisms to evade it.

[21][22] One strategy is intracellular replication, as practised by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or wearing a protective capsule, which prevents lysis by complement and by phagocytes, as in Salmonella.

[23] Bacteroides species are normally mutualistic bacteria, making up a substantial portion of the mammalian gastrointestinal flora.

[28] When the cytoplasmic receptors MDA5 and RIG-I recognize a virus the conformation between the caspase-recruitment domain (CARD) and the CARD-containing adaptor MAVS changes.

[31] Bacteria (and perhaps other prokaryotic organisms), utilize a unique defense mechanism, called the restriction modification system to protect themselves from pathogens, such as bacteriophages.

In this system, bacteria produce enzymes, called restriction endonucleases, that attack and destroy specific regions of the viral DNA of invading bacteriophages.

TLRs are a major class of pattern recognition receptor, that exists in all coelomates (animals with a body-cavity), including humans.

Some invertebrates, including various insects, crabs, and worms utilize a modified form of the complement response known as the prophenoloxidase (proPO) system.

In invertebrates, PRRs trigger proteolytic cascades that degrade proteins and control many of the mechanisms of the innate immune system of invertebrates—including hemolymph coagulation and melanization.

On the other hand, in the horseshoe crab clotting system, components of proteolytic cascades are stored as inactive forms in granules of hemocytes, which are released when foreign molecules, like lipopolysaccharides enter.

Like invertebrates, plants neither generate antibody or T-cell responses nor possess mobile cells that detect and attack pathogens.

Some of these travel through the plant and signal other cells to produce defensive compounds to protect uninfected parts, e.g., leaves.