Phagocyte

[9] Phagocytes are crucial in fighting infections, as well as in maintaining healthy tissues by removing dead and dying cells that have reached the end of their lifespan.

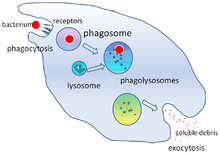

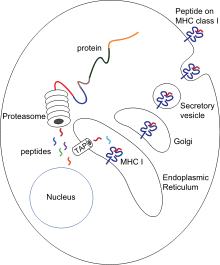

[12] After phagocytosis, macrophages and dendritic cells can also participate in antigen presentation, a process in which a phagocyte moves parts of the ingested material back to its surface.

[17] A year later, Mechnikov studied a fresh water crustacean called Daphnia, a tiny transparent animal that can be examined directly under a microscope.

He went on to extend his observations to the white blood cells of mammals and discovered that the bacterium Bacillus anthracis could be engulfed and killed by phagocytes, a process that he called phagocytosis.

[15] In 1903, Almroth Wright discovered that phagocytosis was reinforced by specific antibodies that he called opsonins, from the Greek opson, "a dressing or relish".

[5] Although the importance of these discoveries slowly gained acceptance during the early twentieth century, the intricate relationships between phagocytes and all the other components of the immune system were not known until the 1980s.

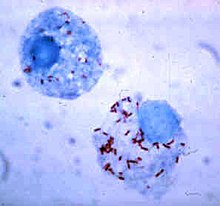

[23][24] Phagocytosis occurs after the foreign body, a bacterial cell, for example, has bound to molecules called "receptors" that are on the surface of the phagocyte.

Macrophages are slow and untidy eaters; they engulf huge quantities of material and frequently release some undigested back into the tissues.

[34] When granules fuse with a phagosome, myeloperoxidase is released into the phagolysosome, and this enzyme uses hydrogen peroxide and chlorine to create hypochlorite, a substance used in domestic bleach.

[14] Myeloperoxidase contains a heme pigment, which accounts for the green color of secretions rich in neutrophils, such as pus and infected sputum.

They can communicate with other cells by producing chemicals called cytokines, which recruit other phagocytes to the site of infections or stimulate dormant lymphocytes.

[54] The adaptive immune system is not dependent on phagocytes but lymphocytes, which produce protective proteins called antibodies, which tag invaders for destruction and prevent viruses from infecting cells.

[55] Phagocytes, in particular dendritic cells and macrophages, stimulate lymphocytes to produce antibodies by an important process called antigen presentation.

[13] Mature macrophages do not travel far from the site of infection, but dendritic cells can reach the body's lymph nodes, where there are millions of lymphocytes.

In this semi-resting state, they clear away dead host cells and other non-infectious debris and rarely take part in antigen presentation.

[67] These chemical signals may include proteins from invading bacteria, clotting system peptides, complement products, and cytokines that have been given off by macrophages located in the tissue near the infection site.

Signals from the infection cause the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels to make a protein called selectin, which neutrophils stick to on passing by.

Most monocytes leave the blood stream after 20–40 hours to travel to tissues and organs and in doing so transform into macrophages[70] or dendritic cells depending on the signals they receive.

[75] Activated macrophages play a potent role in tumor destruction by producing TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen compounds, cationic proteins, and hydrolytic enzymes.

[75] Neutrophils are normally found in the bloodstream and are the most abundant type of phagocyte, constituting 50% to 60% of the total circulating white blood cells.

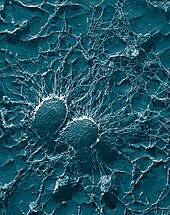

[88][89] Dendritic cells are present in the tissues that are in contact with the external environment, mainly the skin, the inner lining of the nose, the lungs, the stomach, and the intestines.

Treponema pallidum—the bacterium that causes syphilis—hides from phagocytes by coating its surface with fibronectin,[109] which is produced naturally by the body and plays a crucial role in wound healing.

[114] Enteropathogenic species of the genus Yersinia bind with the use of the virulence factor YopH to receptors of phagocytes from which they influence the cells capability to exert phagocytosis.

Staphylococcus aureus, for example, produces the enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase, which break down chemicals—such as hydrogen peroxide—produced by phagocytes to kill bacteria.

After a bacterium is ingested, it may kill the phagocyte by releasing toxins that travel through the phagosome or phagolysosome membrane to target other parts of the cell.

[124] Some species of Leishmania alter the infected macrophage's signalling, repress the production of cytokines and microbicidal molecules—nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species—and compromise antigen presentation.

[129] In the liver, damage by neutrophils can contribute to dysfunction and injury in response to the release of endotoxins produced by bacteria, sepsis, trauma, alcoholic hepatitis, ischemia, and hypovolemic shock resulting from acute hemorrhage.

TNF-α is an important chemical that is released by macrophages that causes the blood in small vessels to clot to prevent an infection from spreading.

[132] If a bacterial infection spreads to the blood, TNF-α is released into vital organs, which can cause vasodilation and a decrease in plasma volume; these in turn can be followed by septic shock.

[134] Amoebae are unicellular protists that separated from the tree leading to metazoa shortly after the divergence of plants, and they share many specific functions with mammalian phagocytic cells.

![A cartoon: 1. The particle is depicted by an oval and the surface of the phagocyte by a straight line. Different smaller shapes are on the line and the oval. 2. The smaller particles on each surface join. 3. The line is now concave and partially wraps around the oval.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Phagocytosis_in_three_steps.png/220px-Phagocytosis_in_three_steps.png)