Hybrid (biology)

In biology, a hybrid is the offspring resulting from combining the qualities of two organisms of different varieties, subspecies, species or genera through sexual reproduction.

This is common in both traditional horticulture and modern agriculture; many commercially useful fruits, flowers, garden herbs, and trees have been produced by hybridization.

Mythological hybrids appear in human culture in forms as diverse as the Minotaur, blends of animals, humans and mythical beasts such as centaurs and sphinxes, and the Nephilim of the Biblical apocrypha described as the wicked sons of fallen angels and attractive women.

Similarly, genetic erosion from monoculture in crop plants may be damaging the gene pools of many species for future breeding.

[5][6] It has been proposed that hybridization could be a useful tool to conserve biodiversity by allowing organisms to adapt, and that efforts to preserve the separateness of a "pure" lineage could harm conservation by lowering the organisms' genetic diversity and adaptive potential, particularly in species with low populations.

[11] From the point of view of animal and plant breeders, there are several kinds of hybrid formed from crosses within a species, such as between different breeds.

The cross between two different homozygous lines produces an F1 hybrid that is heterozygous; having two alleles, one contributed by each parent and typically one is dominant and the other recessive.

[18] In horticulture, the term stable hybrid is used to describe an annual plant that, if grown and bred in a small monoculture free of external pollen (e.g., an air-filtered greenhouse) produces offspring that are "true to type" with respect to phenotype; i.e., a true-breeding organism.

Hybridization occurs between a narrow area across New England, southern Ontario, and the Great Lakes, the "suture region".

[21][22] A permanent hybrid results when only the heterozygous genotype occurs, as in Oenothera lamarckiana,[23] because all homozygous combinations are lethal.

However, in some cases the hybrid organism may display a phenotype that is only weakly (or partially) wild-type, and this may reflect intragenic (interallelic) complementation.

[31] Interordinal hybrids (between different orders) are few, but have been engineered between the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (female) and the sand dollar Dendraster excentricus (male).

The offspring display traits and characteristics of both parents, but are often sterile, preventing gene flow between the species.

[35] A variety of mechanisms limit the success of hybridization, including the large genetic difference between most species.

However, homoploid hybrid speciation (not increasing the number of sets of chromosomes) may be rare: by 1997, only eight natural examples had been fully described.

An economically important example is hybrid maize (corn), which provides a considerable seed yield advantage over open pollinated varieties.

For example, hybrids between a lion and a tigress ("ligers") are much larger than either of the two progenitors, while "tigons" (lioness × tiger) are smaller.

[57] Hybridization is greatly influenced by human impact on the environment,[58] through effects such as habitat fragmentation and species introductions.

Humans have introduced species worldwide to environments for a long time, both intentionally for purposes such as biological control, and unintentionally, as with accidental escapes of individuals.

[58] Conservationists disagree on when is the proper time to give up on a population that is becoming a hybrid swarm, or to try and save the still existing pure individuals.

These hybridization events can result from the introduction of non-native genotypes by humans or through habitat modification, bringing previously isolated species into contact.

[62][63] In agriculture and animal husbandry, the Green Revolution's use of conventional hybridization increased yields by breeding high-yielding varieties.

[73] In 2019, scientists confirmed that a skull found 30 years earlier was a hybrid between the beluga whale and narwhal, dubbed the narluga.

[85] The Colias eurytheme and C. philodice butterflies have retained enough genetic compatibility to produce viable hybrid offspring.

[41] Several commercial fruits including loganberry (Rubus × loganobaccus)[96] and grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi)[97] are hybrids, as are garden herbs such as peppermint (Mentha × piperita),[98] and trees such as the London plane (Platanus × hispanica).

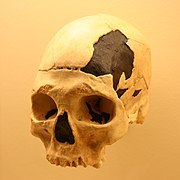

[112] In 1998, a complete prehistorical skeleton found in Portugal, the Lapedo child, had features of both anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals.

[113] Some ancient human skulls with especially large nasal cavities and unusually shaped braincases represent human-Neanderthal hybrids.

A 37,000- to 42,000-year-old human jawbone found in Romania's Oase cave contains traces of Neanderthal ancestry[a] from only four to six generations earlier.

[116] Folk tales and myths sometimes contain mythological hybrids; the Minotaur was the offspring of a human, Pasiphaë, and a white bull.

[117] More often, they are composites of the physical attributes of two or more kinds of animals, mythical beasts, and humans, with no suggestion that they are the result of interbreeding, as in the centaur (man/horse), chimera (goat/lion/snake), hippocamp (fish/horse), and sphinx (woman/lion).