Reinforcement (speciation)

He envisioned a species separated allopatrically, where during secondary contact the two populations mate, producing hybrids with lower fitness.

This favors the evolution of greater prezygotic isolation (differences in behavior or biology that inhibit formation of hybrid zygotes).

Reinforcement is one of the few cases in which selection can favor an increase in prezygotic isolation, influencing the process of speciation directly.

[2] The support for reinforcement has fluctuated since its inception, and terminological confusion and differences in usage over history have led to multiple meanings and complications.

[4][5] Numerous models have been developed to understand its operation in nature, most relying on several facets: genetics, population structures, influences of selection, and mating behaviors.

[9]: 353 His hypothesis differed markedly from the modern conception in that it focused on post-zygotic isolation, strengthened by group selection.

[3]: 367 Dobzhansky's idea gained significant support; he suggested that it illustrated the final step in speciation, for example after an allopatric population comes into secondary contact.

[3]: 353 In the 1980s, many evolutionary biologists began to doubt the plausibility of the idea,[3]: 353 based not on empirical evidence, but largely on the growth of theory that deemed it an unlikely mechanism of reproductive isolation.

By the early 1990s, reinforcement saw a revival in popularity among evolutionary biologists; due primarily from a sudden increase in data—empirical evidence from studies in labs and largely by examples found in nature.

[3]: 372 The most recent theoretical work on speciation has come from several studies (notably from Liou and Price, Kelly and Noor, and Kirkpatrick and Servedio) using highly complex computer simulations; all of which came to similar conclusions: that reinforcement is plausible under several conditions, and in many cases, is easier than previously thought.

[18] Servedio and Noor include any detected increase in prezygotic isolation as reinforcement, as long as it is a response to selection against mating between two different species.

[4] Coyne and Orr contend that, "true reinforcement is restricted to cases in which isolation is enhanced between taxa that can still exchange genes".

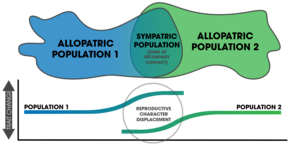

[23] A common signature of reinforcement's occurrence in nature is that of reproductive character displacement; characteristics of a population diverge in sympatry but not allopatry.

[24] Two important factors in the outcome of the process rely on: 1) the specific mechanisms that causes prezygotic isolation, and 2) the number of alleles altered by mutations affecting mate choice.

[26] In sympatric speciation, selection against hybrids is required; therefore reinforcement can play a role, given the evolution of some form of fitness trade-offs.

[27] The underlying genetics of reinforcement can be understood by an ideal model of two haploid populations experiencing an increase in linkage disequilibrium.

[28] A restriction of migration between populations can further increase the chance of reinforcement, as it decreases the probability of the differing genotypes to exchange.

[7] Selection against the hybrids can even be driven by any failure to obtain a mate, as it is effectively indistinguishable from sterility—each circumstance results in no offspring.

Reinforcement's ubiquity is unknown,[4] but the patterns of reproductive character displacement are found across numerous taxa and is considered to be a common occurrence in nature.

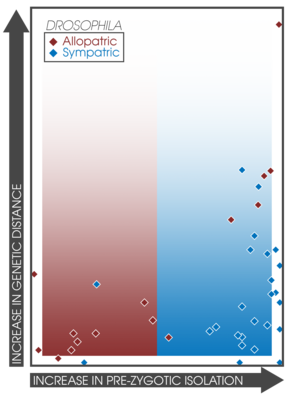

[15] This fact allows for the direct comparison of the strength of prezygotic isolation in sympatry and allopatry between different experiments and studies.

[3]: 363 A survey of the rates of speciation in fish and their associated hybrid zones found similar patterns in sympatry, supporting the occurrence of reinforcement.

[38] Laboratory studies that explicitly test for reinforcement are limited,[3]: 357 with many of the experiments having been conducted on Drosophila fruit flies.

Natural selection may drive the reduction of an overlap of niches between species instead of acting to reduce hybridization[3]: 377 Though one experiment in stickleback fish that explicitly tested this hypotheses found no evidence.

[7][44] Additionally, when there is a low cost to female mate preferences, changes in male phenotypes can result, expressing a pattern identical to that of reproductive character displacement.

[7][20][3]: 369 Most rely on theoretical work which suggested that the antagonism between the forces of natural selection and gene flow were the largest barriers to its feasibility.

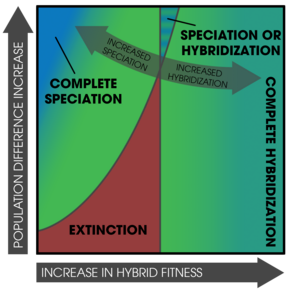

[18][3]: 372 Concerns about hybrid fitness playing a role in reinforcement has led to objections based on the relationship between selection and recombination.

[5][3]: 369 That is, if gene flow is not zero (if hybrids aren't completely unfit), selection cannot drive the fixation of alleles for prezygotic isolation.

[26][31] Recent studies suggest reinforcement can occur under a wider range of conditions than previously thought[29][46][3]: 372–373 and that the effect of gene flow can be overcome by selection.

[50] This natural setting was reproduced in the laboratory, directly modeling reinforcement: the removal of some hybrids and the allowance of varying levels of gene flow.

[51] The results of the experiment strongly suggested that reinforcement works under a variety of conditions, with the evolution of sexual isolation arising in 5–10 fruit fly generations.

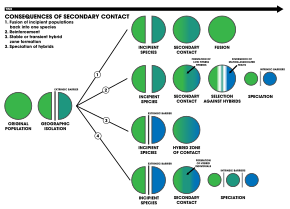

1. An extrinsic barrier separates a species population into two but they come into contact before reproductive isolation is sufficient to result in speciation. The two populations fuse back into one species

2. Speciation by reinforcement

3. Two separated populations stay genetically distinct while hybrid swarms form in the zone of contact

4. Genome recombination results in speciation of the two populations, with an additional hybrid species . All three species are separated by intrinsic reproductive barriers [ 19 ]