Ionic bonding

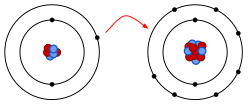

In simpler words, an ionic bond results from the transfer of electrons from a metal to a non-metal to obtain a full valence shell for both atoms.

Ionic compounds generally have a high melting point, depending on the charge of the ions they consist of.

As a result, weakly electronegative atoms tend to distort their electron cloud and form cations.

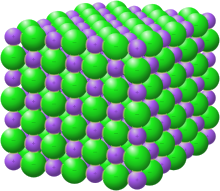

The electrostatic attraction between the anions and cations leads to the formation of a solid with a crystallographic lattice in which the ions are stacked in an alternating fashion.

For compounds that are transitional to the alloys and possess mixed ionic and metallic bonding, this may not be the case anymore.

The charge of the resulting ions is a major factor in the strength of ionic bonding, e.g. a salt C+A− is held together by electrostatic forces roughly four times weaker than C2+A2− according to Coulomb's law, where C and A represent a generic cation and anion respectively.

Pauling's rules provide guidelines for predicting and rationalizing the crystal structures of ionic crystals For a solid crystalline ionic compound the enthalpy change in forming the solid from gaseous ions is termed the lattice energy.

The Born–Landé equation gives a reasonable fit to the lattice energy of, e.g., sodium chloride, where the calculated (predicted) value is −756 kJ/mol, which compares to −787 kJ/mol using the Born–Haber cycle.

[6] The strength of salt bridges is most often evaluated by measurements of equilibria between molecules containing cationic and anionic sites, most often in solution.

This polarization of the negative ion leads to a build-up of extra charge density between the two nuclei, that is, to partial covalency.

However, 2+ ions (Be2+) or even 1+ (Li+) show some polarizing power because their sizes are so small (e.g., LiI is ionic but has some covalent bonding present).

Note that this is not the ionic polarization effect that refers to the displacement of ions in the lattice due to the application of an electric field.

The larger the difference in electronegativity between the two types of atoms involved in the bonding, the more ionic (polar) it is.

[10] Ionic character in covalent bonds can be directly measured for atoms having quadrupolar nuclei (2H, 14N, 81,79Br, 35,37Cl or 127I).

Interactions between the nuclear quadrupole moments Q and the electric field gradients (EFG) are characterized via the nuclear quadrupole coupling constants where the eqzz term corresponds to the principal component of the EFG tensor and e is the elementary charge.

In turn, the electric field gradient opens the way to description of bonding modes in molecules when the QCC values are accurately determined by NMR or NQR methods.

[2] In such cases, the resulting bonding often requires description in terms of a band structure consisting of gigantic molecular orbitals spanning the entire crystal.