Ionization

Ionization or ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes.

Ionization can occur through radioactive decay by the internal conversion process, in which an excited nucleus transfers its energy to one of the inner-shell electrons causing it to be ejected.

The ionization process is widely used in a variety of equipment in fundamental science (e.g., mass spectrometry) and in medical treatment (e.g., radiation therapy).

[12][13] Negatively charged ions[14] are produced when a free electron collides with an atom and is subsequently trapped inside the electric potential barrier, releasing any excess energy.

Kinematically complete experiments,[15] i.e. experiments in which the complete momentum vector of all collision fragments (the scattered projectile, the recoiling target-ion, and the ejected electron) are determined, have contributed to major advances in the theoretical understanding of the few-body problem in recent years.

It is a cascade reaction involving electrons in a region with a sufficiently high electric field in a gaseous medium that can be ionized, such as air.

The two free electrons then travel towards the anode and gain sufficient energy from the electric field to cause impact ionization when the next collisions occur; and so on.

This is a valuable tool for establishing and understanding the ordering of electrons in atomic orbitals without going into the details of wave functions or the ionization process.

The periodic abrupt decrease in ionization potential after rare gas atoms, for instance, indicates the emergence of a new shell in alkali metals.

In addition, the local maximums in the ionization energy plot, moving from left to right in a row, are indicative of s, p, d, and f sub-shells.

Classical physics and the Bohr model of the atom can qualitatively explain photoionization and collision-mediated ionization.

[27] In general, the analytic solutions are not available, and the approximations required for manageable numerical calculations do not provide accurate enough results.

However, when the laser intensity is sufficiently high, the detailed structure of the atom or molecule can be ignored and analytic solution for the ionization rate is possible.

In practice, tunnel ionization is observable when the atom or molecule is interacting with near-infrared strong laser pulses.

[29] In this model the perturbation of the ground state by the laser field is neglected and the details of atomic structure in determining the ionization probability are not taken into account.

The major difficulty with Keldysh's model was its neglect of the effects of Coulomb interaction on the final state of the electron.

As it is observed from figure, the Coulomb field is not very small in magnitude compared to the potential of the laser at larger distances from the nucleus.

Larochelle et al.[32] have compared the theoretically predicted ion versus intensity curves of rare gas atoms interacting with a Ti:Sapphire laser with experimental measurement.

They have shown that the total ionization rate predicted by the PPT model fit very well the experimental ion yields for all rare gases in the intermediate regime of the Keldysh parameter.

In 1992, de Boer and Muller [39] showed that Xe atoms subjected to short laser pulses could survive in the highly excited states 4f, 5f, and 6f.

These states were believed to have been excited by the dynamic Stark shift of the levels into multiphoton resonance with the field during the rising part of the laser pulse.

Subsequent evolution of the laser pulse did not completely ionize these states, leaving behind some highly excited atoms.

In 1996, using a very stable laser and by minimizing the masking effects of the focal region expansion with increasing intensity, Talebpour et al.[41] observed structures on the curves of singly charged ions of Xe, Kr and Ar.

[42] The phenomenon of non-sequential ionization (NSI) of atoms exposed to intense laser fields has been a subject of many theoretical and experimental studies since 1983.

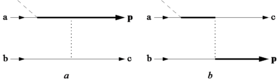

The propagation of the ionized electron in the laser field, during which it absorbs other photons (ATI), is shown by the full thick line.

The ionization of inner valence electrons are responsible for the fragmentation of polyatomic molecules in strong laser fields.

According to a qualitative model[54][55] the dissociation of the molecules occurs through a three-step mechanism: The short pulse induced molecular fragmentation may be used as an ion source for high performance mass spectroscopy.

The KH frame is thus employed in theoretical studies of strong-field ionization and atomic stabilization (a predicted phenomenon in which the ionization probability of an atom in a high-intensity, high-frequency field actually decreases for intensities above a certain threshold) in conjunction with high-frequency Floquet theory.

[61] The KF frame was successfully applied for different problems as well e.g. for higher-hamonic generation from a metal surface in a powerful laser field[62] A substance may dissociate without necessarily producing ions.

When salt is dissociated, its constituent ions are simply surrounded by water molecules and their effects are visible (e.g. the solution becomes electrolytic).