Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe

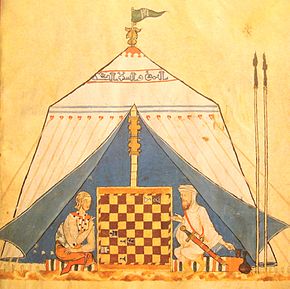

During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was an important contributor to the global cultural scene, innovating and supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant.

The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in Sicily and in Spain, particularly in Toledo (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114–1187, following the conquest of the city by Spanish Christians in 1085).

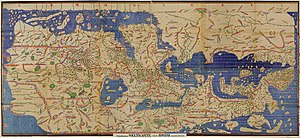

The Moroccan Muhammad al-Idrisi wrote The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands or Tabula Rogeriana, one of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages, for Roger.

From the 11th to the 14th centuries, numerous European students attended Muslim centers of higher learning (which the author calls "universities") to study medicine, philosophy, mathematics, cosmography and other subjects.

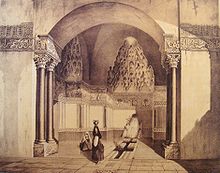

The Islamic world then kept, translated, and developed many of these texts, especially in centers of learning such as Baghdad, where a "House of Wisdom" with thousands of manuscripts existed as early as 832.

The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, Muslim sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun, Carthage citizen Constantine the African who translated Greek medical texts, and Al-Khwarizmi's collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age.

[12] The main significance of Latin Avicennism lies in the interpretation of Avicennian doctrines such as the nature of the soul and his existence-essence distinction, along with the debates and censure that they raised in scholastic Europe.

This was particularly the case in Paris, where so-called Arabic culture was proscribed in 1210, though the influence of his psychology and theory of knowledge upon William of Auvergne and Albertus Magnus have been noted.

[17] George Makdisi (1989) has suggested that two particular aspects of Renaissance humanism have their roots in the medieval Islamic world, the "art of dictation, called in Latin, ars dictaminis," and "the humanist attitude toward classical language".

He notes that dictation was a necessary part of Arabic scholarship (where the vowel sounds need to be added correctly based on the spoken word), and argues that the medieval Italian use of the term "ars dictaminis" makes best sense in this context.

[18] During the Islamic Golden Age, certain advances were made in scientific fields, notably in mathematics and astronomy (algebra, spherical trigonometry), and in chemistry, etc.

The method of algorism for performing arithmetic with the Hindu–Arabic numeral system was developed by the Persian al-Khwarizmi in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci (1170–1250).

These scholars were interested in ancient Greek philosophical and scientific texts (notably the Almagest) which were not obtainable in Latin in Western Europe, but which had survived and been translated into Arabic in the Muslim world.

Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī's Ta'rikh al-Hind and Kitab al-qanun al-Mas’udi were translated into Latin as Indica and Canon Mas’udicus respectively.

[38] A short verse used by Fulbert of Chartres (952-970 –1028) to help remember some of the brightest stars in the sky gives us the earliest known use of Arabic loanwords in a Latin text:[43] "Aldebaran stands out in Taurus, Menke and Rigel in Gemini, and Frons and bright Calbalazet in Leo.

In religion, for example, John Wycliffe, the intellectual progenitor of the Protestant Reformation, referred to Alhazen in discussing the seven deadly sins in terms of the distortions in the seven types of mirrors analyzed in De aspectibus.

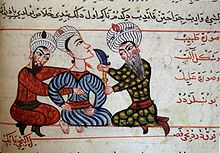

[55] Avicenna noted the contagious nature of some infectious diseases (which he attributed to "traces" left in the air by a sick person), and discussed how to effectively test new medicines.

Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi wrote the Comprehensive Book of Medicine, with its careful description of and distinction between measles and smallpox, which was also influential in Europe.

[60] Various fruits and vegetables were introduced to Europe in this period via the Middle East and North Africa, some from as far as China and India, including the artichoke, spinach, and aubergine.

[63] Medieval art in Sicily is interesting stylistically because of the mixture of Norman, Arab and Byzantine influences in areas such as mosaics and metal inlays, sculpture, and bronze-working.

[68] Another reason might be that artist wished to express a cultural universality for the Christian faith, by blending together various written languages, at a time when the church had strong international ambitions.

[69] Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, the Levant or the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were a significant sign of wealth and luxury in Europe, as demonstrated by their frequent occurrence as important decorative features in paintings from the 13th century and continuing into the Baroque period.

[72] Some scholars believe that the troubadors may have had Arabian origins, with Magda Bogin stating that the Arab poetic and musical tradition was one of several influences on European "courtly love poetry".

[73] Évariste Lévi-Provençal and other scholars stated that three lines of a poem by William IX of Aquitaine were in some form of Arabic, indicating a potential Andalusian origin for his works.

However, Beech adds that William and his father did have Spanish individuals within their extended family, and that while there is no evidence he himself knew Arabic, he may have been friendly with some European Christians who could speak the language.

Also transmitted via Muslim influence, a silk industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and esparto grass, which grew wild in the more arid parts, was collected and turned into various articles.

"[91] These innovations made it possible for some industrial operations that were previously served by manual labour or draught animals to be driven by machinery in medieval Europe.

In Sicily, Malta and Southern Italy from about 913 tarì gold coins of Islamic origin were minted in great number by the Normans, Hohenstaufens and the early Angevins rulers.

[99][100] According to Janet Abu-Lughod: The preferred specie for international transactions before the 13th century, in Europe as well as the Middle East and even India, were the gold coins struck by Byzantium and then Egypt.

[101]It was first suggested by Miguel Asín Palacios in 1919 that Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, considered the greatest epic of Italian literature, derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology, such as the Hadith and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi.