Laron syndrome

[4][5] The genetic origins of these individuals have been traced back to Mediterranean, South Asian, and Semitic ancestors, with the latter group comprising the majority of cases.

[11] LS is recognized as being part of a spectrum of conditions that affect the Hypothalamic–pituitary–somatotropic axis and cause significant derangements in human growth, development, and metabolism.

[1][12] In addition to short stature, other characteristic physical symptoms of LS include: prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge, underdevelopment of mandible, truncal obesity,[7] and micropenis in males.

[13] Additional physical features include delayed bone age, hypogonadism, blue sclera, high-pitched voice, acrohypoplasia, sparse hair growth, and crowded teeth.

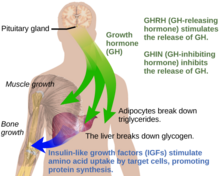

[9] Under normal circumstances in humans, growth hormone (GH) is released in a pulsatile fashion from cells known as somatotrophs in the anterior pituitary gland.

[16] Molecular genetic investigations have shown that LS is mainly associated with autosomal recessive mutations in the gene for the growth hormone receptor (GHR).

[14] The gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of LS is to perform a genetic analysis with PCR to identify the precise molecular defect in the GH receptor gene.

In 2010 and 2014, a group of parents, led by Santiago Vasco Morales, filed lawsuits requesting the Ecuadorian government to provide the necessary comprehensive treatment.

However, due to the lack of response and non-compliance with court rulings, the parents sought assistance from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

[32] A 2019 study of individuals with isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD type 1B) in Itabaianinha County, Brazil, demonstrated a phenotype consistent with Laron syndrome.

[33] Researchers found that these humans had similarly extended healthspan, with resistance to cancer and attenuated effects of aging, but neither patients with LS nor IGHD experienced an increase in their overall lifespan.

[1] The countries of origin of these patients include Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Iran, Malta, Italy, Argentina, Ecuador, and Peru.

[1] Recent publications have proposed that Homo floresiensis represented a population with widespread Laron syndrome, based upon the many similarities of skeletal remains found in Indonesia with LS.

[38] Israeli pediatric endocrinologist Zvi Laron, along with Athalia Pertzelan, Avinoam Galatzer, Liora Kornreich, Dalia Peled, Rivka Kauli, and Beatrice Klinger published the earliest clinical studies of individuals with LS beginning in 1966.

[39][40][1] Among their first 22 patients, Laron and colleagues noted consanguineous genealogy of Israeli and Palestinian ancestry with distinct physical characteristics resembling hypopituitarism.