Vladimir Lenin

He was expelled from Kazan Imperial University for participating in protests against the Tsarist government, and devoted the following years to a law degree before relocating to Saint Petersburg in 1893 and becoming a leading Marxist activist.

Lenin's government abolished private ownership of land, nationalised major industry and banks, withdrew from the war by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and promoted world revolution through the Communist International.

[11] Both of Lenin's parents were monarchists and liberal conservatives, being committed to the emancipation reform of 1861 introduced by the reformist Tsar Alexander II; they avoided political radicals and there is no evidence that the police ever put them under surveillance for subversive thought.

[31] In May 1890, Maria, who retained societal influence as the widow of a nobleman, persuaded the authorities to allow Lenin to take his exams externally at the University of St Petersburg, where he obtained the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours.

Deemed only a minor threat to the government, he was exiled to Shushenskoye, Minusinsky District, where he was kept under police surveillance; he was nevertheless able to correspond with other revolutionaries, many of whom visited him, and permitted to go on trips to swim in the Yenisei River and to hunt duck and snipe.

[63] They continued their political agitation, as Lenin wrote for Iskra and drafted the RSDLP programme, attacking ideological dissenters and external critics, particularly the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR),[64] a Narodnik agrarian-socialist group founded in 1901.

[86] Recognising that membership fees and donations from a few wealthy sympathisers were insufficient to finance the Bolsheviks' activities, Lenin endorsed the idea of robbing post offices, railway stations, trains, and banks.

[90] As the Tsarist government cracked down on opposition, both by disbanding Russia's legislative assembly, the Second Duma, and by ordering its secret police, the Okhrana, to arrest revolutionaries, Lenin fled Finland for Switzerland.

[103] Meanwhile, at a Paris meeting in June 1911, the RSDLP Central Committee decided to move their focus of operations back to Russia, ordering the closure of the Bolshevik Centre and its newspaper, Proletari.

[129] Arriving at Petrograd's Finland Station in April, Lenin gave a speech to Bolshevik supporters condemning the Provisional Government and again calling for a continent-wide European proletarian revolution.

Premier Alexander Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet, including its Bolshevik members, for help, allowing the revolutionaries to organise workers as Red Guards to defend the city.

[149] Critics of the plan, Zinoviev and Kamenev, argued that Russian workers would not support a violent coup against the regime and that there was no clear evidence for Lenin's assertion that all of Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.

[168] Although ultimate power officially rested with Sovnarkom and the Executive Committee (VTSIK) elected by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets (ARCS), the Communist Party was de facto in control of Russia, as acknowledged by its members at the time.

[220] By contrast, other Bolsheviks, in particular Nikolai Bukharin and the Left Communists, believed that peace with the Central Powers would be a betrayal of international socialism and that Russia should instead wage "a war of revolutionary defence" that would provoke an uprising of the German proletariat against their own government.

[233] It resulted in massive territorial losses for Russia, with 26% of the former Empire's population, 37% of its agricultural harvest area, 28% of its industry, 26% of its railway tracks, and three-quarters of its coal and iron deposits being transferred to German control.

[236] After the Treaty, Sovnarkom focused on trying to foment proletarian revolution in Germany, issuing an array of anti-war and anti-government publications in the country; the German government retaliated by expelling Russia's diplomats.

Lenin expected Russia's aristocracy and bourgeoisie to oppose his government but believed that the numerical superiority of the lower classes, coupled with the Bolsheviks' organizational skills, would ensure a swift victory.

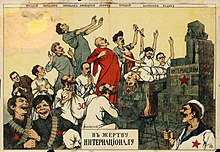

[326] During the first conference, Lenin spoke to the delegates, lambasting the parliamentary path to socialism espoused by revisionist Marxists like Kautsky and repeating his calls for a violent overthrow of Europe's bourgeoisie governments.

[330] For this conference, he authored "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder, a short book articulating his criticism of elements within the British and German communist parties who refused to enter their nations' parliamentary systems and trade unions; instead, he urged them to do so to advance the revolutionary cause.

[381] With Lenin's support, the government also succeeded in virtually eradicating Menshevism in Russia by expelling all Mensheviks from state institutions and enterprises in March 1923 and then imprisoning the party's membership in concentration camps.

Stalin had suggested that both the forcibly Sovietized Georgia and neighbouring countries like Azerbaijan and Armenia, which were all invaded and occupied by the Red Army, should be merged into the Russian state, despite the protestations of their local Soviet-installed governments.

[410] On 23 January, mourners from the Communist Party, trade unions, and Soviets visited his Gorki home to inspect the body, which was carried aloft in a red coffin by leading Bolsheviks.

[456] Prior to taking power in 1917, he was concerned that ethnic and national minorities would make the Soviet state ungovernable with their calls for independence; according to the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, Lenin thus encouraged Stalin to develop "a theory that offered the ideal of autonomy and the right of secession without necessarily having to grant either".

[457] On taking power, Lenin called for the dismantling of the bonds that had forced minority ethnic groups to remain in the Russian Empire and espoused their right to secede but also expected them to reunite immediately in the spirit of proletariat internationalism.

[526] Conversely, the majority of Western historians have perceived him as a person who manipulated events to attain and then retain political power, moreover, considering his ideas as attempts to ideologically justify his pragmatic policies.

[540] Ryan contends that the leftist historian Paul Le Blanc "makes a quite valid point that the personal qualities that led Lenin to brutal policies were not necessarily any stronger than in some of the major Western leaders of the twentieth century".

"[543] Some left-wing intellectuals, among them Slavoj Žižek, Alain Badiou, Lars T. Lih, and Fredric Jameson, advocate reviving Lenin's uncompromising revolutionary spirit to address contemporary global problems.

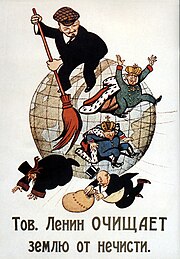

[545] According to historian Nina Tumarkin, it represented the world's "most elaborate cult of a revolutionary leader" since that of George Washington in the United States,[546] and has been repeatedly described as "quasi-religious" in nature.

President Boris Yeltsin, with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, intended to close the mausoleum and bury Lenin next to his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova, at the Volkov Cemetery in Saint Petersburg.

[520] Conversely, many later Western communists, such as Manuel Azcárate and Jean Ellenstein, who were involved in the Eurocommunist movement, expressed the view that Lenin and his ideas were irrelevant to their own objectives, thereby embracing a Marxist but not Marxist–Leninist perspective.