Lunar resources

[1] Regolith (lunar soil) is the easiest product to obtain; it can provide radiation and micrometeoroid protection as well as construction and paving material by melting.

[11] For in situ resource utilization (ISRU) to be applied successfully on the Moon, landing site selection is imperative, as well as identifying suitable surface operations and technologies.

[13] Elements known to be present on the lunar surface include, among others, hydrogen (H),[1][14] oxygen (O), silicon (Si), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), aluminium (Al), manganese (Mn) and titanium (Ti).

[23] The Kilopower nuclear fission system is being developed for reliable electric power generation that could enable long-duration crewed bases on the Moon, Mars and destinations beyond.

Protests by the general public therefore often focus on the phaseout of RTGs (instead recommending alternative power sources), due to an overestimation of the dangers of radiation.

Furthermore, while helium-3 is required for one possible pathway of nuclear fusion, others instead rely on nuclides which are more easily obtained on Earth, such as tritium, lithium or deuterium.

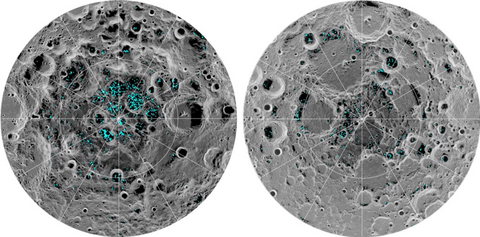

[36] Water may have been delivered to the Moon over geological timescales by the regular bombardment of water-bearing comets, asteroids and meteoroids[37] or continuously produced in situ by the hydrogen ions (protons) of the solar wind impacting oxygen-bearing minerals.

[1][45] Extraction would be quite energy-demanding, but some prominent lunar magnetic anomalies are suspected as being due to surviving Fe-rich meteoritic debris.

[46] Free iron also exists in the regolith (0.5% by weight) naturally alloyed with nickel and cobalt and it can easily be extracted by simple magnets after grinding.

On earth this is usually done via carbothermic reduction, a process that requires carbon, an element in comparatively short supply on the moon.

[53][54] Rare-earth elements are used to manufacture everything from electric or hybrid vehicles, wind turbines, electronic devices and clean energy technologies.

Potassium and phosphorus are two of the three essential plant nutrients, the third being fixed nitrogen (hence NPK fertilizer) any agricultural activity on the moon would need a supply of those elements — whether sourced in situ or brought from elsewhere e.g. earth.

[75] Due to extremely low temperatures, permanently shadowed regions of the Moon's poles have cold traps which possibly contain solid carbon dioxide.

One of the primary requirements will be to provide construction materials to build habitats, storage bins, landing pads, roads and other infrastructure.

[81][82] Unprocessed lunar soil, also called regolith, may be turned into usable structural components,[83][84] through techniques such as sintering, hot-pressing, liquification, the cast basalt method,[21][85] and 3D printing.

[87] The lunar soil, although it poses a problem for any mechanical moving parts, can be mixed with carbon nanotubes and epoxies in the construction of telescope mirrors up to 50 meters in diameter.

The lunar soil is composed of a blend of silica and iron-containing compounds that may be fused into a glass-like solid using microwave radiation.

[92][93] The European Space Agency working in 2013 with an independent architectural firm, tested a 3D-printed structure that could be constructed of lunar regolith for use as a Moon base.

"[96] In early 2014, NASA funded a small study at the University of Southern California to further develop the Contour Crafting 3D printing technique.

[99] Long-term planning is required to achieve sustainability and ensure that future generations are not faced with a barren lunar wasteland by wanton practices.

[104] India's Chandrayaan programme is focused in understanding the lunar water cycle first, and on mapping mineral location and concentrations from orbit and in situ.

Russia's Luna-Glob programme is planning and developing a series of landers, rovers and orbiters for prospecting and science exploration, and to eventually employ in situ resource utilization (ISRU) methods with the intent to construct and operate their own crewed lunar base in the 2030s.

[1][118] In 2024, an American startup called Interlune announced plans to mine Helium on the Moon for export back on Earth.

[120] It has been proposed that smelters could process the basaltic lava to break it down into pure calcium, aluminium, oxygen, iron, titanium, magnesium, and silica glass.

[121] The European Space Agency has awarded funding to Metalysis in 2020 to further develop the FFC Cambridge process to extract titanium from regolith while generating oxygen as a byproduct.

[121][45] Another proposal envisions the use of fluorine brought from Earth as potassium fluoride to separate the raw materials from the lunar rocks.

[123] Although Luna landers scattered pennants of the Soviet Union on the Moon, and United States flags were symbolically planted at their landing sites by the Apollo astronauts, no nation claims ownership of any part of the Moon's surface,[124] and the international legal status of mining space resources is unclear and controversial.

[130] The OST treaty offers imprecise guidelines to newer space activities such as lunar and asteroid mining,[131] and it therefore remains under contention whether the extraction of resources falls within the prohibitive language of appropriation or whether the use encompasses the commercial use and exploitation.

"[132] The 1979 Moon Treaty is a proposed framework of laws to develop a regime of detailed rules and procedures for orderly resource exploitation.

[137][138] The last attempt to define acceptable detailed rules for exploitation, ended in June 2018, after S. Neil Hosenball, who was the NASA General Counsel and chief US negotiator for the Moon Treaty, decided that negotiation of the mining rules in the Moon Treaty should be delayed until the feasibility of exploitation of lunar resources had been established.