March of Intellect

[2] 1814 saw the first use of the term the 'march of Mind' as a poem written by Mary Russell Mitford for the Lancastrian Society,[3] and the latter's work in bringing education to children was soon rivalled by the efforts of the Established Church.

[6] At the same time, the spread of print culture, artisan coffee houses, and, from 1823 onwards, Mechanics' Institutes,[7] as well as the growth of Literary and Philosophical Societies,[8] meant something of a revolution in adult reading habits.

On the one hand, the Philosophic Whigs, spearheaded by Brougham, offered a new vision of a society progressing into the future: Thackeray would write of "the three cant terms of the Radical spouters...'the March of Intellect', 'the intelligence of the working classes', and 'the schoolmaster abroad'".

But the same phenomenon of the March of Intellect was equally hailed by conservatives as epitomising everything they rejected about the new age:[14] liberalism, machinery, education, social unrest – all became the focus of a critique under the guise of the 'March'.

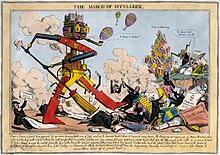

[16] Heath used machines, steam-powered vehicles and other forms of technology in his work to mock liberal Whiggish ambitions that problems in society could be solved through widespread education.

For example, Robert Seymour's cartoon entitled 'The March of Intellect' (c.1828) in which a giant automaton sweeps away quacks, delayed parliamentary bills and court cases, can be seen as apocalyptic in its attempt to improve society.

[22] Continuing concerns related more to ameliorating its effects than turning back the clock – philosophers fearing over-education would reduce moral and physical fibre,[23] poets seeking to preserve individuality in the face of the utilitarian march.