Gospel of Mark

[9] The hypothesis of Marcan priority (that Mark was written first) continues to be held by the majority of scholars today, and there is a new recognition of the author as an artist and theologian using a range of literary devices to convey his conception of Jesus as the authoritative yet suffering Son of God.

[19] Whether the Gospels were composed before or after 70 AD, according to Bas van Os, the lifetime of various eyewitnesses that includes Jesus's own family through the end of the First Century is very likely statistically.

[26][27] Theologian and former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams proposed that Libya was a possible setting, as it was the location of Cyrene and there is a long-held Arabic tradition of Mark's residence there.

[29] Ancient biographies were concerned with providing examples for readers to emulate while preserving and promoting the subject's reputation and memory, and also included morals and rhetoric in their works.

[31] Christian churches were small communities of believers, often based on households (an autocratic patriarch plus extended family, slaves, freedmen, and other clients), and the evangelists often wrote on two levels: one the "historical" presentation of the story of Jesus, the other dealing with the concerns of the author's own day.

Uniting these ideas was the common thread of apocalyptic expectation: Both Jews and Christians believed that the end of history was at hand, that God would very soon come to punish their enemies and establish his own rule, and that they were at the centre of his plans.

[35] The new movement spread around the eastern Mediterranean and to Rome and further west, and assumed a distinct identity, although the groups within it remained extremely diverse.

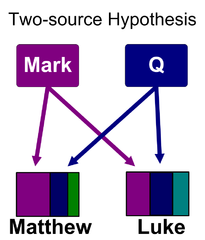

The fact that they share so much material verbatim and yet also exhibit important differences has led to several hypotheses explaining their interdependence, a phenomenon termed the synoptic problem.

[36] The hypothesis of Marcan priority is held by the majority of scholars today, and there is a new recognition of the author as an artist and theologian using a range of literary devices to convey his conception of Jesus as the authoritative yet suffering Son of God.

Firstly, in 1901 William Wrede put forward an argument that the "Messianic Secret" motif within Mark had actually been a creation of the early church instead of a reflection of the historical Jesus.

In 1919, Karl Ludwig Schmidt argued that the links between episodes in Mark were a literary invention of the author, meaning that the text could not be used as evidence in attempts to reconstruct the chronology of Jesus' mission.

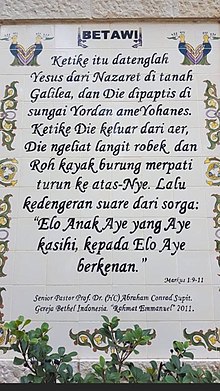

Galilean ministry John the Baptist (1:1–8) Baptism of Jesus (1:9–11) Temptation of Jesus (1:12–13) Return to Galilee (1:14) Good News (1:15) First disciples (1:16–20) Capernaum's synagogue (1:21–28) Peter's mother-in-law (1:29–31) Exorcising at sunset (1:32–34) A leper (1:35–45) A paralytic (2:1–2:12) Calling of Matthew (2:13–17) Fasting and wineskins (2:18–22) Lord of the Sabbath (2:23–28) Man with withered hand (3:1–6) Withdrawing to the sea (3:7–3:12) Commissioning the Twelve (3:13–19) Blind mute (3:20–26) Strong man (3:27) Eternal sin (3:28–30) Jesus' true relatives (3:31–35) Parable of the Sower (4:1–9,13-20) Purpose of parables (4:10–12,33-34) Lamp under a bushel (4:21–23) Mote and Beam (4:24–25) Growing seed and Mustard seed (4:26–32) Calming the storm (4:35–41) Demon named Legion (5:1–20) Daughter of Jairus (5:21–43) Hometown rejection (6:1–6) Instructions for the Twelve (6:7–13) Beheading of John (6:14–29) Feeding the 5000 (6:30–44) Walking on water (6:45–52) Fringe of his cloak heals (6:53–56) Discourse on Defilement (7:1–23) Canaanite woman's daughter (7:24–30) Deaf mute (7:31–37) Feeding the 4000 (8:1–9) No sign will be given (8:10–21) Healing with spit (8:22–26) Peter's confession (8:27–30) Jesus predicts his death (8:31–33, 9:30–32, 10:32–34) Instructions for followers (8:34–9:1) Transfiguration (9:2–13) Possessed boy (9:14–29) Teaching in Capernaum (9:33–50) 2.

(12:35–40) Widow's mite (12:41–44) Olivet Discourse (13) Plot to kill Jesus (14:1–2) Anointing (14:3–9) Bargain of Judas (14:10–11) Last Supper (14:12–26) Denial of Peter (14:27–31,66-72) Agony in the Garden (14:32–42) Kiss of Judas (14:43–45) Arrest (14:46–52) Before the High Priest (14:53–65) Pilate's court (15:1–15) Soldiers mock Jesus (15:16–20) Simon of Cyrene (15:21) Crucifixion (15:22–41) Entombment (15:42–47) Empty tomb (16:1–8) The Longer Ending (16:9–20) Post-resurrection appearances (16:9–13) Great Commission (16:14–18) Ascension (16:19) Dispersion of the Apostles (16:20) There is no agreement on the structure of Mark.

[44] A further generally recognised turning point comes at the end of chapter 10, when Jesus and his followers arrive in Jerusalem and the foreseen confrontation with the Temple authorities begins, leading R.T. France to characterise Mark as a three-act drama.

[45] James Edwards in his 2002 commentary points out that the gospel can be seen as a series of questions asking first who Jesus is (the answer being that he is the messiah), then what form his mission takes (a mission of suffering culminating in the crucifixion and resurrection, events only to be understood when the questions are answered), while another scholar, C. Myers, has made what Edwards calls a "compelling case" for recognising the incidents of Jesus' baptism, transfiguration and crucifixion, at the beginning, middle and end of the gospel, as three key moments, each with common elements, and each portrayed in an apocalyptic light.

[51] The author introduces his work as "gospel", meaning "good news", a literal translation of the Greek "evangelion"[52] – he uses the word more often than any other writer in the New Testament except Paul.

[52] Like the other gospels, Mark was written to confirm the identity of Jesus as eschatological deliverer – the purpose of terms such as "messiah" and "son of God".

[54] In Mark, the disciples, especially the Twelve, move from lack of perception of Jesus to rejection of the "way of suffering" to flight and denial – even the women who received the first proclamation of his resurrection can be seen as failures for not reporting the good news.

[62][59] "There was [...] no period in the history of the [Roman] empire in which the magician was not considered an enemy of society," subject to penalties ranging from exile to death, says Classical scholar Ramsay MacMullen.

[69] Where it appears in the Hebrew scriptures it meant Israel as God's people, or the king at his coronation, or angels, as well as the suffering righteous man.

[85][86] One of the most significant Jewish meanings of this epithet is a reference to an earthly king adopted by God as his son at his enthronement, legitimizing his rule over Israel.

[87] In Hellenistic culture, in contrast, the phrase meant a "divine man", covering legendary heroes like Hercules, god-kings like the Egyptian pharaohs, or famous philosophers like Plato.

[87] Mark's "Son of David" is Hellenistic, his Jesus predicting that his mission involves suffering, death and resurrection, and, by implication, not military glory and conquest.

"; Matthew, the next gospel to be written, repeats this word for word but manages to make clear that Jesus's death is the beginning of the resurrection of Israel; Luke has a still more positive picture, replacing Mark's (and Matthew's) cry of despair with one of submission to God's will ("Father, into your hands I commend my spirit"); while John, the last gospel, has Jesus dying without apparent suffering in fulfillment of the divine plan.