Martensite

As a result of the quenching, the face-centered cubic austenite transforms to a highly strained body-centered tetragonal form called martensite that is supersaturated with carbon.

The shear deformations that result produce a large number of dislocations, which is a primary strengthening mechanism of steels.

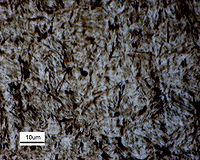

For steel with greater than 1% carbon, it will form a plate-like structure called plate martensite.

If the cooling rate is slower than the critical cooling rate, some amount of pearlite will form, starting at the grain boundaries where it will grow into the grains until the Ms temperature is reached, then the remaining austenite transforms into martensite at about half the speed of sound in steel.

[1][3] The growth of martensite phase requires very little thermal activation energy because the process is a diffusionless transformation, which results in the subtle but rapid rearrangement of atomic positions, and has been known to occur even at cryogenic temperatures.

[4] Of considerably greater importance than the volume change is the shear strain, which has a magnitude of about 0.26 and which determines the shape of the plates of martensite.

Since chemical processes (the attainment of equilibrium) accelerate at higher temperature, martensite is easily destroyed by the application of heat.