Maya civilization

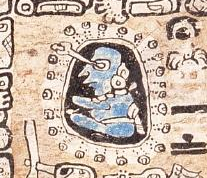

The Maya developed sophisticated art forms using both perishable and non-perishable materials, including wood, jade, obsidian, ceramics, sculpted stone monuments, stucco, and finely painted murals.

The Maya developed a highly complex series of interlocking ritual calendars, and employed mathematics that included one of the earliest known instances of the explicit zero in human history.

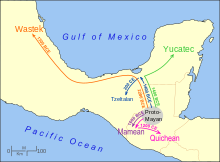

[28] Settlements were established around 1800 BC in the Soconusco region of the Pacific coast, and the Maya were already cultivating the staple crops of maize, beans, squash, and chili pepper.

[43] This period marked the peak of large-scale construction and urbanism, the recording of monumental inscriptions, and demonstrated significant intellectual and artistic development, particularly in the southern lowland regions.

[62] During the 9th century AD, the central Maya region suffered major political collapse, marked by the abandonment of cities, the ending of dynasties, and a northward shift in activity.

[46][63] No universally accepted theory explains this collapse, but it likely had a combination of causes, including endemic internecine warfare, overpopulation resulting in severe environmental degradation, and drought.

[81] After the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish in 1521, Hernán Cortés despatched Pedro de Alvarado to Guatemala with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, 4 cannons, and thousands of allied warriors from central Mexico;[82] they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.

[92] The 260-day tzolkʼin ritual calendar continues in use in modern Maya communities in the highlands of Guatemala and Chiapas,[93] and millions of Mayan-language speakers inhabit the territory in which their ancestors developed their civilization.

[96] In 1839, American traveller and writer John Lloyd Stephens set out to visit a number of Maya sites with English architect and draftsman Frederick Catherwood.

[106] During the Late Preclassic, the Maya political system coalesced into a theopolitical form, where elite ideology justified the ruler's authority, and was reinforced by public display, ritual, and religion.

The divine authority invested within the ruler was such that the king was able to mobilize both the aristocracy and commoners in executing huge infrastructure projects, apparently with no police force or standing army.

[116] By the Late Classic, when populations had grown enormously and hundreds of cities were connected in a complex web of political hierarchies, the wealthy segment of society multiplied.

Military campaigns were launched for a variety of reasons, including the control of trade routes and tribute, raids to take captives, scaling up to the complete destruction of an enemy state.

[141] Maya armies of the Contact period were highly disciplined, and warriors participated in regular training exercises and drills; every able-bodied adult male was available for military service.

Cities such as Kaminaljuyu and Qʼumarkaj in the Guatemalan Highlands, and Chalchuapa in El Salvador, variously controlled access to the sources of obsidian at different points in Maya history.

In the Early Classic, Chichen Itza was at the hub of an extensive trade network that imported gold discs from Colombia and Panama, and turquoise from Los Cerrillos, New Mexico.

[173] At some Classic period cities, archaeologists have tentatively identified formal arcade-style masonry architecture and parallel alignments of scattered stones as the permanent foundations of market stalls.

Such secondary representations show the elite of the Maya court adorned with sumptuous cloths, generally these would have been cotton, but jaguar pelts and deer hides are also shown.

[206] The Ik-style polychrome ceramic corpus, including finely painted plates and cylindrical vessels, originated in Late Classic Motul de San José.

The subject matter of the vessels includes courtly life from the Petén region in the 8th century AD, such as diplomatic meetings, feasting, bloodletting, scenes of warriors and the sacrifice of prisoners of war.

[210] Additional graffiti, not part of the planned decoration, was incised into the stucco of interior walls, floors, and benches, in a wide variety of buildings, including temples, residences, and storerooms.

[250] Throughout Maya history, ballcourts maintained a characteristic form consisting of an ɪ shape, with a central playing area terminating in two transverse end zones.

[257] Puuc sites replaced rubble cores with lime cement, resulting in stronger walls, and also strengthened their corbel arches;[260] this allowed Puuc-style cities to build freestanding entrance archways.

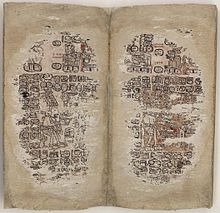

[281][282] Archaeology conducted at Maya sites often reveals other fragments, rectangular lumps of plaster and paint chips which were codices; these tantalizing remains are, however, too severely damaged for any inscriptions to have survived, most of the organic material having decayed.

[329] The Spinden Correlation would shift the Long Count dates back by 260 years; it also accords with the documentary evidence, and is better suited to the archaeology of the Yucatán Peninsula, but presents problems with the rest of the Maya region.

Although Maya astronomy was mainly used by the priesthood to comprehend past cycles of time, and project them into the future to produce prophecy, it also had some practical applications, such as providing aid in crop planting and harvesting.

[337] In common with the rest of Mesoamerica, the Maya believed in a supernatural realm inhabited by an array of powerful deities who needed to be placated with ceremonial offerings and ritual practices.

[345] The Maya priesthood was a closed group, drawing its members from the established elite; by the Early Classic they were recording increasingly complex ritual information in their hieroglyphic books, including astronomical observations, calendrical cycles, history and mythology.

[348] In AD 738, the vassal king Kʼakʼ Tiliw Chan Yopaat of Quiriguá captured his overlord, Uaxaclajuun Ubʼaah Kʼawiil of Copán and a few days later ritually decapitated him.

[350][348] During the Postclassic period, the most common form of human sacrifice was heart extraction, influenced by the rites of the Aztecs in the Valley of Mexico;[348] this usually took place in the courtyard of a temple, or upon the summit of the pyramid.