Medieval cuisine

As each level of society attempted to imitate the one above it, innovations from international trade and foreign wars from the 12th century onward gradually disseminated through the upper middle class of medieval cities.

Even if most people respected these restrictions and usually made penance when they violated them, there were also numerous ways of circumventing them, a conflict of ideals and practice summarized by writer Bridget Ann Henisch: It is the nature of man to build the most complicated cage of rules and regulations in which to trap himself, and then, with equal ingenuity and zest, to bend his brain to the problem of wriggling triumphantly out again.

All foodstuffs were also classified on scales ranging from hot to cold and moist to dry, according to the four bodily humours theory proposed by Galen that dominated Western medical science from late Antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages.

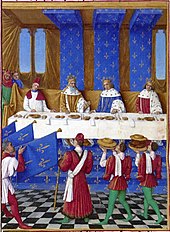

In the 13th century, English bishop Robert Grosseteste advised the Countess of Lincoln: "forbid dinners and suppers out of hall, in secret and in private rooms, for from this arises waste and no honor to the lord and lady."

Social codes made it difficult for women to uphold the ideal of immaculate neatness and delicacy while enjoying a meal, so the wife of the host often dined in private with her entourage or ate very little at such feasts.

The hierarchical nature of society was reinforced by etiquette where the lower ranked were expected to help the higher, the younger to assist the elder, and men to spare women the risk of sullying dress and reputation by having to handle food in an unwomanly fashion.

Shared drinking cups were common even at lavish banquets for all but those who sat at the high table, as was the standard etiquette of breaking bread and carving meat for one's fellow diners.

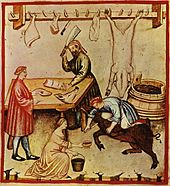

[34] Food was mostly served on plates or in stew pots, and diners would take their share from the dishes and place it on trenchers of stale bread, wood or pewter with the help of spoons or bare hands.

The princess' insistence on having her food cut up by her eunuch servants and then eating the pieces with a golden fork shocked and upset the diners so much that there was a claim that Peter Damian, Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, later interpreted her refined foreign manners as pride and referred to her as "... the Venetian Doge's wife, whose body, after her excessive delicacy, entirely rotted away.

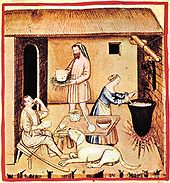

There were also portable ovens designed to be filled with food and then buried in hot coals, and even larger ones on wheels that were used to sell pies in the streets of medieval towns.

In wealthy households one of the most common tools was the mortar and sieve cloth, since many medieval recipes called for food to be finely chopped, mashed, strained and seasoned either before or after cooking.

[45] The kitchen staff of huge noble or royal courts occasionally numbered in the hundreds: pantlers, bakers, waferers, sauciers, larderers, butchers, carvers, page boys, milkmaids, butlers, and numerous scullions.

Guidelines on how to prepare for a two-day banquet can be found in the cookbook Du fait de cuisine ('On cookery') written in 1420 in part to compete with the court of Burgundy[46] by Maistre Chiquart, master chef of Duke Amadeus VIII of Savoy.

Microbial modification was also encouraged, however, by a number of methods; grains and fruits were turned into alcoholic drinks thus killing any pathogens, and milk was fermented and curdled into a multitude of cheeses or buttermilk.

In the early 15th century, the English monk John Lydgate articulated the beliefs of many of his contemporaries by proclaiming that "Hoot ffir [fire] and smoke makith many an angry cook.

[54] One of the common constituents of a medieval meal, either as part of a banquet or as a small snack, were sops, pieces of bread with which a liquid like wine, soup, broth, or sauce could be soaked up and eaten.

But at the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215), Pope Innocent III explicitly prohibited the eating of barnacle geese during Lent, arguing that they lived and fed like ducks and so were of the same nature as other birds.

A wide range of mollusks including oysters, mussels, and scallops were eaten by coastal and river-dwelling populations, and freshwater crayfish were seen as a desirable alternative to meat during fish days.

Perhaps as a consequence of the Norman Conquest and the travelling of nobles between France and England, one French variant described in the 14th century cookbook Le Menagier de Paris was called godale (most likely a direct borrowing from the English 'good ale') and was made from barley and spelt, but without hops.

Though most of the breweries were small family businesses that employed at most eight to ten people, regular production allowed for investment in better equipment and increased experimentation with new recipes and brewing techniques.

[99] The early use of various distillates, alcoholic or not, was varied, but it was primarily culinary or medicinal; grape syrup mixed with sugar and spices was prescribed for a variety of ailments, and rosewater was used as a perfume and cooking ingredient and for hand washing.

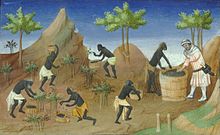

[102] Spices were among the most luxurious products available in the Middle Ages, the most common being black pepper, cinnamon (and the cheaper alternative cassia), cumin, nutmeg, ginger, and cloves.

They all had to be imported from plantations in Asia and Africa, which made them extremely expensive, and gave them social cachet such that pepper, for example, was hoarded, traded and conspicuously donated in the manner of gold bullion.

[103] While pepper was the most common spice, the most exclusive (though not the most obscure in its origin) was saffron, used as much for its vivid yellow-red color as for its flavor, for according to the humours, yellow signified hot and dry, valued qualities;[104] turmeric provided a yellow substitute, and touches of gilding at banquets supplied both the medieval love of ostentatious show and Galenic dietary lore: at the sumptuous banquet that Cardinal Riario offered to Eleanor of Naples in June 1473, the bread was gilded.

This last type of non-dairy milk product is probably the single most common ingredient in late medieval cooking and blended the aroma of spices and sour liquids with a mild taste and creamy texture.

There were a wide variety of fritters, crêpes with sugar, sweet custards and darioles, almond milk and eggs in a pastry shell that could also include fruit and sometimes even bone marrow or fish.

[113] Le Ménagier de Paris ("Parisian Household Book"), written in 1393, includes a quiche recipe made with three kinds of cheese, eggs, beet greens, spinach, fennel fronds, and parsley.

From the south, the Arabs also brought the art of ice cream-making that produced sorbet and several examples of sweet cakes and pastries; cassata alla Siciliana (from Arabic qas'ah, the term for the terracotta bowl with which it was shaped), made from marzipan, sponge cake with sweetened ricotta, and cannoli alla Siciliana, originally cappelli di turchi ('Turkish hats'), fried, chilled pastry tubes with a sweet cheese filling.

[119] The common method of grinding and mashing ingredients into pastes and the many potages and sauces has been used as an argument that most adults within the medieval nobility lost their teeth at an early age, and hence were forced to eat nothing but porridge, soup and ground-up meat.

Towards the onset of the early modern period, in 1474, the Vatican librarian Bartolomeo Platina wrote De honesta voluptate et valetudine ("On honorable pleasure and health") and the physician Iodocus Willich edited Apicius in Zürich in 1563.