Metal

[6][7] The strength and resilience of some metals has led to their frequent use in, for example, high-rise building and bridge construction, as well as most vehicles, many home appliances, tools, pipes, and railroad tracks.

Consequently, semiconductors and nonmetals are poor conductors, although they can carry some current when doped with elements that introduce additional partially occupied energy states at higher temperatures.

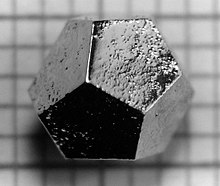

Plutonium increases its electrical conductivity when heated in the temperature range of around −175 to +125 °C, with anomalously large thermal expansion coefficient and a phase change from monoclinic to face-centered cubic near 100 °C.

Taking into account the positive potential caused by the arrangement of the ion cores enables consideration of the electronic band structure and binding energy of a metal.

Theoretical and experimental evidence suggests that these uninvestigated elements should be metals,[32] except for oganesson (Og) which DFT calculations indicate would be a semiconductor.

[9] They have partially filled states at the Fermi level[9] so are good thermal and electrical conductors, and there is often significant charge transfer from the transition metal atoms to the nitrogen.

Despite the overall scarcity of some heavier metals such as copper, they can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.

The magnetic field shields the Earth from the charged particles of the solar wind, and cosmic rays that would otherwise strip away the upper atmosphere (including the ozone layer that limits the transmission of ultraviolet radiation).

In 2010, the International Resource Panel, hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme published reports on metal stocks that exist within society[79] and their recycling rates.

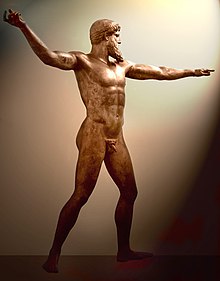

[80] The discovery of bronze (an alloy of copper with arsenic or tin) enabled people to create metal objects which were harder and more durable than previously possible.

Bronze tools, weapons, armor, and building materials such as decorative tiles were harder and more durable than their stone and copper ("Chalcolithic") predecessors.

The earliest known production of steel, an iron-carbon alloy, is seen in pieces of ironware excavated from an archaeological site in Anatolia (Kaman-Kalehöyük) which are nearly 4,000 years old, dating from 1800 BCE.

[84][85] From about 500 BCE sword-makers of Toledo, Spain, were making early forms of alloy steel by adding a mineral called wolframite, which contained tungsten and manganese, to iron ore (and carbon).

"[86] In pre-Columbian America, objects made of tumbaga, an alloy of copper and gold, started being produced in Panama and Costa Rica between 300 and 500 CE.

Small metal sculptures were common and an extensive range of tumbaga (and gold) ornaments comprised the usual regalia of persons of high status.

This theory reinforced the belief that all metals were destined to become gold in the bowels of the earth through the proper combinations of heat, digestion, time, and elimination of contaminants, all of which could be developed and hastened through the knowledge and methods of alchemy.

The first systematic text on the arts of mining and metallurgy was De la Pirotechnia (1540) by Vannoccio Biringuccio, which treats the examination, fusion, and working of metals.

Sixteen years later, Georgius Agricola published De Re Metallica in 1556, an account of the profession of mining, metallurgy, and the accessory arts and sciences, an extensive treatise on the chemical industry through the sixteenth century.

The ancient Greek writers seem to have been ignorant of bismuth, wherefore Ammonius rightly states that there are many species of metals, animals, and plants which are unknown to us.

[89] Platinum, the third precious metal after gold and silver, was discovered in Ecuador during the period 1736 to 1744 by the Spanish astronomer Antonio de Ulloa and his colleague the mathematician Jorge Juan y Santacilia.

In the 1790s, Joseph Priestley and the Dutch chemist Martinus van Marum observed the effect of metal surfaces on the dehydrogenation of alcohol, a development which subsequently led, in 1831, to the industrial scale synthesis of sulphuric acid using a platinum catalyst.

In 1803, cerium was the first of the lanthanide metals to be discovered, in Bastnäs, Sweden by Jöns Jakob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger, and independently by Martin Heinrich Klaproth in Germany.

They have subsequently found uses in cell phones, magnets, lasers, lighting, batteries, catalytic converters, and in other applications enabling modern technologies.

Due to its high tensile strength and low cost, steel came to be a major component used in buildings, infrastructure, tools, ships, automobiles, machines, appliances, and weapons.

Superalloys composed of combinations of Fe, Ni, Co, and Cr, and lesser amounts of W, Mo, Ta, Nb, Ti, and Al were developed shortly after World War II for use in high performance engines, operating at elevated temperatures (above 650 °C (1,200 °F)).

The successful development of the atomic bomb at the end of World War II sparked further efforts to synthesize new elements, nearly all of which are, or are expected to be, metals, and all of which are radioactive.

Amorphous metals are produced in several ways, including extremely rapid cooling, physical vapor deposition, solid-state reaction, ion irradiation, and mechanical alloying.

Compared to conventional alloys with only one or two base metals, HEAs have considerably better strength-to-weight ratios, higher tensile strength, and greater resistance to fracturing, corrosion, and oxidation.

Although HEAs were described as early as 1981, significant interest did not develop until the 2010s; they continue to be a focus of research in materials science and engineering because of their desirable properties.

During mechanical testing, it has been found that polycrystalline Ti3SiC2 cylinders can be repeatedly compressed at room temperature, up to stresses of 1 GPa, and fully recover upon the removal of the load.

(a) Brittle fracture

(b) Ductile fracture

(c) Completely ductile fracture