Mineral evolution

It postulates that mineralogy on planets and moons becomes increasingly complex as a result of changes in the physical, chemical and biological environment.

In the Solar System, the number of mineral species has grown from about a dozen to over 5400 as a result of three processes: separation and concentration of elements; greater ranges of temperature and pressure coupled with the action of volatiles; and new chemical pathways provided by living organisms.

The remaining minerals, more than two-thirds of the total, were the result of chemical changes mediated by living organisms, with the largest increase occurring after the Great Oxygenation Event.

Some mineral-forming processes no longer occur, such as those that produced certain minerals in enstatite chondrites that are unstable on Earth in its oxidized state.

[4] Mineral formation became possible after heavier elements, including carbon, oxygen, silicon and nitrogen, were synthesized in stars.

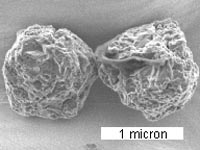

[1][5] Evidence of these minerals can be found in interstellar grains incorporated into primitive meteorites called chondrites, which are essentially cosmic sedimentary rocks.

[10] However, the defining elements for many mineral groups, such as boron in borates and phosphorus in phosphates, were at first only present in concentrations of parts per million or less.

In addition, some of the dates are uncertain; for example, estimates of the onset of modern plate tectonics range from 4.5 Ga to 1.0 Ga.[14] In the first era, the Sun ignited, heating the surrounding molecular cloud.

[8][12] Before 4.56 Ga, the presolar nebula was a dense molecular cloud consisting of hydrogen and helium gas with dispersed dust grains.

Heating from radionuclides melted the ice and the water reacted with olivine-rich rocks, forming phyllosilicates, oxides such as magnetite, sulfides such as pyrrhotite, the carbonates dolomite and calcite, and sulfates such as gypsum.

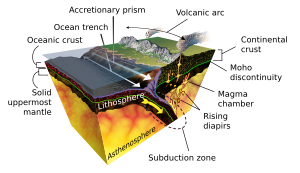

Shock and heat from bombardment and eventual melting produced minerals such as ringwoodite, a major component of Earth's mantle.

[1] Stage 3 began with a crust made of mafic (high in iron and magnesium) and ultramafic rocks such as basalt.

[1] One of the few sources of direct information on mineralogy in this stage is mineral inclusions in zircon crystals, which date as far back as 4.4 Ga.

For Earth, where this stage coincides with the Hadean Eon, the total number of widely occurring minerals is estimated to be 420, with over 100 more that were rare.

Cycles of melting concentrated rare elements such as lithium, beryllium, boron, niobium, tantalum and uranium to the point where they could form 500 new minerals.

Many of these are concentrated in exceptionally coarse-grained rocks called pegmatites that are typically found in dikes and veins near larger igneous masses.

[12] With the onset of plate tectonics, subduction carried crust and water down, leading to fluid-rock interactions and more concentration of rare elements.

[20] When the concentration of oxygen molecules in the atmosphere reached 1% of the present level, the chemical reactions during weathering were much like they are today.

The more oxidized layer of ocean water near the surface slowly deepened at the expense of the anoxic depths, but there did not seem to be any dramatic change in climate, biology or mineralogy.

Many of the world's most valuable reserves of lead, zinc and silver, are found in rocks from this time, as well as rich sources of beryllium, boron and uranium minerals.

In all, over 64 mineral phases have been identified in living organisms, including metal sulfides, oxides, hydroxides and silicates;[18] over two dozen have been found in the human body.

The mineralogical novelties included organic minerals that have been found in carbon-rich remnants of life such as coal and black shales.

[1] Strictly speaking, purely biogenic minerals are not recognized by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) unless geological processes are also involved.

[23] However, humans have had such an impact on the surface of the planet that geologists are considering the introduction of a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, to reflect these changes.

[17][26] Subsequently, Hazen and co-authors catalogued 208 minerals that are officially recognized by the IMA but are primarily or exclusively the result of human activities.

[30][31] Another theory argues that calcium-borate minerals such as colemanite and borate, and possibly also molybdate, may have been needed for the first ribonucleic acid (RNA) to form.

Before life developed pigments to protect it from damaging ultraviolet rays, a thin layer of quartz could shield it while allowing enough light through for photosynthesis.

This remarkably long hiatus is attributed to a sulfide-rich ocean, which led to rapid deposition of the mineral cinnabar.

They have highs and lows that are linked with the supercontinent cycle, although it is not clear whether this is due to changes in subduction activity or preservation.

[39] Charles Meyer, finding that the ores of some elements are distributed over a wider time span than others, attributed the difference to the effects of tectonics and biomass on the surface chemistry, particularly free oxygen and carbon.