Ming–Tibet relations

The Wanli Emperor made attempts to re-establish Ming–Tibetan relations after the Mongol–Tibetan alliance initiated in 1578, which affected the foreign policy of the subsequent Qing dynasty in its support for the Dalai Lama of the Gelug school.

[21][24] Instead of recognizing the Phagmodru ruler, the Hongwu Emperor sided with the Karmapa of the nearer Kham region and southeastern Tibet, sending envoys out in the winter of 1372–1373 to ask the Yuan officeholders to renew their titles for the new Ming court.

[36] The late Turrell V. Wylie, a former professor of the University of Washington, and Li Tieh-tseng argue that the reliability of the heavily censored History of Ming as a credible source on Sino-Tibetan relations is questionable, in the light of modern scholarship.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art also noted that in spite of the gradual assimilation of Yuan monarchs, the Mongol rulers largely ignored the literati and imposed harsh policies discriminating against southern Chinese.

[15] David M. Robinson contends that various edicts and laws issued by the Hongwu Emperor, founder of the Ming dynasty, seem to reject the Mongol influence in China with the banning of Mongolian marriage and burial practices, clothing, speech and even music.

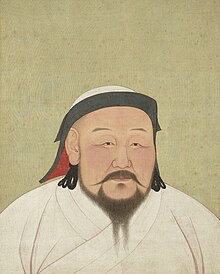

[58] The Yongle Emperor was far more explicit in invoking a comparison between his rule and that of Kublai Khan, as reflected in his very active foreign policy, projection of Ming Chinese power abroad and expansionist military campaigns.

[59] Following the 1449 Tumu Crisis, the Ming government actively discouraged further immigration of Mongol peoples (favoring occasional relocation policies for those who already lived in China).

[69] Van Praag asserts that Changchub Gyaltsen's ambitions were to "restore to Tibet the glories of its Imperial Age" by reinstating secular administration, promoting "national culture and traditions," and installing a law code that survived into the 20th century.

Had the fact been made known to the public that Ch'eng-tsu's repeated invitations extended to Tsong-ka-pa were declined, the Emperor's prestige and dignity would have been considered as lowered to a contemptible degree, especially at a time when his policy to show high favours toward lamas was by no means popular and had already caused resentment among the people.

"[98] Patricia Ann Berger writes that the Yongle Emperor's courting and granting of titles to lamas was his attempt to "resurrect the relationship between China and Tibet established earlier by the Yuan dynastic founder Khubilai Khan and his guru Phagpa.

"[49] The Information Office of the State Council of the PRC preserves an edict of the Zhengtong Emperor (r. 1435–1449) addressed to the Karmapa in 1445, written after the latter's agent had brought holy relics to the Ming court.

[99] Zhengtong had the following message delivered to the Great Treasure Prince of Dharma, the Karmapa: Out of compassion, Buddha taught people to be good and persuaded them to embrace his doctrines.

[28] The Ming government imposed a monopoly on tea production and attempted to regulate this trade with state-supervised markets, but these collapsed in 1449 due to military failures and internal ecological and commercial pressures on the tea-producing regions.

[100] While the Ming dynasty traded horses with Tibet, it upheld a policy of outlawing border markets in the north, which Laird sees as an effort to punish the Mongols for their raids and to "drive them from the frontiers of China.

John D. Langlois writes that there was unrest in Tibet and western Sichuan, which the Marquis Mu Ying (沐英) was commissioned to quell in November 1378 after he established a Taozhou garrison in Gansu.

After his death in 1395 from either a drug overdose or toxins mixed with his medicine, Zhu Shuang was posthumously reprimanded by his father for various actions, including those against Tibetan prisoners of war (involving the slaughter of nearly two-thousand captives).

[119] Norbu states that the Ming dynasty, preoccupied with the Mongol threat to the north, could not spare additional armed forces to enforce or back up their claim of sovereignty over Tibet; instead, they relied on "Confucian instruments of tribute relations" of heaping unlimited number of titles and gifts on Tibetan lamas through acts of diplomacy.

"[121] P. Christiaan Klieger argues that the Ming court's patronage of high Tibetan lamas "was designed to help stabilize border regions and protect trade routes.

"[122] Historians Luciano Petech and Sato Hisashi argue that the Ming upheld a "divide-and-rule" policy towards a weak and politically fragmented Tibet after the Sakya regime had fallen.

[27] Despite protests by the Grand Secretary Liang Chu, in 1515 the Zhengde Emperor sent his eunuch official Liu Yun of the Palace Chancellery on a mission to invite this Karmapa to Beijing.

[131] Josef Kolmaš, a sinologist, Tibetologist, and Professor of Oriental Studies at the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, writes that it was during the Qing dynasty "that developments took place on the basis of which Tibet came to be considered an organic part of China, both practically and theoretically subject to the Chinese central government.

[122] He adds that "Although agreements were made between Tibetan leaders and Mongol khans, Ming and Qing emperors, it was the Republic of China and its Communist successors that assumed the former imperial tributaries and subject states as integral parts of the Chinese nation-state.

"[122] Marina Illich, a scholar of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, while discussing the life of the Gelug lama Chankya Rolpe Dorje (1717–1786), mentions the limitations of both Western and Chinese modern scholarship in their interpretation of Tibetan sources.

[136] With the death of Zhengde and ascension of Jiajing, the politics at court shifted in favor of the Neo-Confucian establishment which not only rejected the Portuguese embassy of Fernão Pires de Andrade (d. 1523),[136] but had a predisposed animosity towards Tibetan Buddhism and lamas.

[140] After Altan Khan made peace with the Ming dynasty in 1571, he invited the third hierarch of the Gelug—Sönam Gyatso (1543–1588)—to meet him in Amdo (modern Qinghai) in 1578, where he accidentally bestowed him and his two predecessors with the title of Dalai Lama—"Ocean Teacher".

[155] In 1621, the Ü-Tsang king died and was succeeded by his young son Karma Tenkyong, an event which stymied the war effort as the latter accepted the six-year-old Lozang Gyatso as the new Dalai Lama.

[157][158] Soon after the victory in Ü-Tsang, Güshi Khan organized a welcoming ceremony for Lozang Gyatso once he arrived a day's ride from Shigatse, presenting his conquest of Tibet as a gift to the Dalai Lama.

[159] In a second ceremony held within the main hall of the Shigatse fortress, Güshi Khan enthroned the Dalai Lama as the ruler of Tibet, but conferred the actual governing authority to the regent Sonam Chöpel.

[161] However, Rawski states that he eventually "expanded his own authority by presenting himself as Avalokiteśvara through the performance of rituals," by building the Potala Palace and other structures on traditional religious sites, and by emphasizing lineage reincarnation through written biographies.

[166] Van Praag states that Tibet and the Dalai Lama's power was recognized by the "Manchu Emperor, the Mongolian Khans and Princes, and the rulers of Ladakh, Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Sikkim.