Nucleic acid double helix

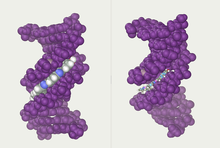

In molecular biology, the term double helix[1] refers to the structure formed by double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA.

The structure was discovered by Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, her student Raymond Gosling, James Watson, and Francis Crick,[2] while the term "double helix" entered popular culture with the 1968 publication of Watson's The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA.

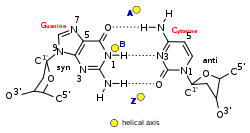

The DNA double helix biopolymer of nucleic acid is held together by nucleotides which base pair together.

[5] The double-helix model of DNA structure was first published in the journal Nature by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953,[6] (X,Y,Z coordinates in 1954[7]) based on the work of Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling, who took the crucial X-ray diffraction image of DNA labeled as "Photo 51",[8][9] and Maurice Wilkins, Alexander Stokes, and Herbert Wilson,[10] and base-pairing chemical and biochemical information by Erwin Chargaff.

[17] The realization that the structure of DNA is that of a double-helix elucidated the mechanism of base pairing by which genetic information is stored and copied in living organisms and is widely considered one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

Crick, Wilkins, and Watson each received one-third of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to the discovery.

[21] The cell avoids this problem by allowing its DNA-melting enzymes (helicases) to work concurrently with topoisomerases, which can chemically cleave the phosphate backbone of one of the strands so that it can swivel around the other.

The double helix has a right-hand twist that makes one complete turn about its axis every 10.4–10.5 base pairs in solution.

This frequency of twist (termed the helical pitch) depends largely on stacking forces that each base exerts on its neighbours in the chain.

Segments of DNA that cells have methylated for regulatory purposes may adopt the Z geometry, in which the strands turn about the helical axis the opposite way to A-DNA and B-DNA.

Other conformations are possible; A-DNA, B-DNA, C-DNA, E-DNA,[28] L-DNA (the enantiomeric form of D-DNA),[29] P-DNA,[30] S-DNA, Z-DNA, etc.

As a result, proteins like transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contacts to the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.

[39] Alternative non-helical models were briefly considered in the late 1970s as a potential solution to problems in DNA replication in plasmids and chromatin.

The variation is largely due to base stacking energies and the residues which extend into the minor and major grooves.

[47] Consistent with the worm-like chain model is the observation that bending DNA is also described by Hooke's law at very small (sub-piconewton) forces.

For DNA segments less than the persistence length, the bending force is approximately constant and behaviour deviates from the worm-like chain predictions.

As bend angle increases then steric hindrances and ability to roll the residues relative to each other also play a role, especially in the minor groove.

When DNA is in solution, it undergoes continuous structural variations due to the energy available in the thermal bath of the solvent.

Under sufficient tension and positive torque, DNA is thought to undergo a phase transition with the bases splaying outwards and the phosphates moving to the middle.

These structures have not yet been definitively characterised due to the difficulty of carrying out atomic-resolution imaging in solution while under applied force although many computer simulation studies have been made (for example,[50][51]).

Periodic fracture of the base-pair stack with a break occurring once per three bp (therefore one out of every three bp-bp steps) has been proposed as a regular structure which preserves planarity of the base-stacking and releases the appropriate amount of extension,[52] with the term "Σ-DNA" introduced as a mnemonic, with the three right-facing points of the Sigma character serving as a reminder of the three grouped base pairs.

A DNA segment with excess or insufficient helical twisting is referred to, respectively, as positively or negatively supercoiled.

DNA in vivo is typically negatively supercoiled, which facilitates the unwinding (melting) of the double-helix required for RNA transcription.

Linear sections of DNA are also commonly bound to proteins or physical structures (such as membranes) to form closed topological loops.

In a paper published in 1976, Crick outlined the problem as follows: In considering supercoils formed by closed double-stranded molecules of DNA certain mathematical concepts, such as the linking number and the twist, are needed.

[55] However, when experimentally determined structures of the nucleosome displayed an over-twisted left-handed wrap of DNA around the histone octamer,[56][57] this paradox was considered to be solved by the scientific community.