DNA nanotechnology

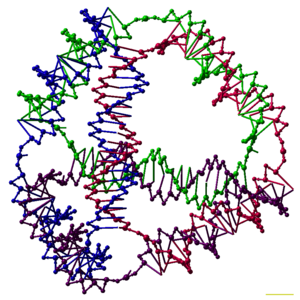

Researchers in the field have created static structures such as two- and three-dimensional crystal lattices, nanotubes, polyhedra, and arbitrary shapes, and functional devices such as molecular machines and DNA computers.

This allows for the rational design of base sequences that will selectively assemble to form complex target structures with precisely controlled nanoscale features.

[2] Seeman's original motivation was to create a three-dimensional DNA lattice for orienting other large molecules, which would simplify their crystallographic study by eliminating the difficult process of obtaining pure crystals.

[5][6] In 1991, Seeman's laboratory published a report on the synthesis of a cube made of DNA, the first synthetic three-dimensional nucleic acid nanostructure, for which he received the 1995 Feynman Prize in Nanotechnology.

[9] The next advance was to translate this into mechanical motion, and in 2004 and 2005, several DNA walker systems were demonstrated by the groups of Seeman, Niles Pierce, Andrew Turberfield, and Chengde Mao.

[8] DNA nanotechnology was initially met with some skepticism due to the unusual non-biological use of nucleic acids as materials for building structures and doing computation, and the preponderance of proof of principle experiments that extended the abilities of the field but were far from actual applications.

Seeman's 1991 paper on the synthesis of the DNA cube was rejected by the journal Science after one reviewer praised its originality while another criticized it for its lack of biological relevance.

Structural DNA nanotechnology, sometimes abbreviated as SDN, focuses on synthesizing and characterizing nucleic acid complexes and materials that assemble into a static, equilibrium end state.

On the other hand, dynamic DNA nanotechnology focuses on complexes with useful non-equilibrium behavior such as the ability to reconfigure based on a chemical or physical stimulus.

[23] In addition, reconfigurable structures and devices can be made using functional nucleic acids such as deoxyribozymes and ribozymes, which can perform chemical reactions, and aptamers, which can bind to specific proteins or small molecules.

[25] Structural DNA nanotechnology, sometimes abbreviated as SDN, focuses on synthesizing and characterizing nucleic acid complexes and materials where the assembly has a static, equilibrium endpoint.

Small nucleic acid complexes can be equipped with sticky ends and combined into larger two-dimensional periodic lattices containing a specific tessellated pattern of the individual molecular tiles.

DNA origami was first demonstrated for two-dimensional shapes, such as a smiley face, a coarse map of the Western Hemisphere, and the Mona Lisa painting.

The goal is to use the self-assembly of the nucleic acid structures to template the assembly of the nanoparticles hosted on them, controlling their position and in some cases orientation.

[23][10] The earliest such device made use of the transition between the B-DNA and Z-DNA forms to respond to a change in buffer conditions by undergoing a twisting motion.

Subsequent systems could change states based upon the presence of control strands, allowing multiple devices to be independently operated in solution.

[62] Another approach is to make use of restriction enzymes or deoxyribozymes to cleave the strands and cause the walker to move forward, which has the advantage of running autonomously.

[69] DNA nanotechnology provides one of the few ways to form designed, complex structures with precise control over nanoscale features.

The earliest such application envisaged for the field, and one still in development, is in crystallography, where molecules that are difficult to crystallize in isolation could be arranged within a three-dimensional nucleic acid lattice, allowing determination of their structure.

[73] In a study conducted by a group of scientists from iNANO and CDNA centers in Aarhus University, researchers were able to construct a small multi-switchable 3D DNA Box Origami.

[6] Scientists at Oxford University reported the self-assembly of four short strands of synthetic DNA into a cage which can enter cells and survive for at least 48 hours.

The fluorescently labeled DNA tetrahedra were found to remain intact in the laboratory cultured human kidney cells despite the attack by cellular enzymes after two days.

Delivery of the interfering RNA for treatment has showed some success using polymer or lipid, but there are limits of safety and imprecise targeting, in addition to short shelf life in the blood stream.

[89] Similar to naturally occurring protein ion channels, this ensemble of synthetic DNA-made counterparts thereby spans multiple orders of magnitude in conductance.

The study of the membrane-inserting single DNA duplex showed that current must also flow on the DNA-lipid interface as no central channel lumen is present in the design that lets ions pass across the lipid bilayer.

Utilizing this effect, they designed a synthetic DNA-built enzyme that flips lipids in biological membranes orders of magnitudes faster than naturally occurring proteins called scramblases.

This design step determines the secondary structure, or the positions of the base pairs that hold the individual strands together in the desired shape.

This is done either through simple, faster heuristic methods such as sequence symmetry minimization, or by using a full nearest-neighbor thermodynamic model, which is more accurate but slower and more computationally intensive.

[94] Strands can be purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis if needed,[95] and precise concentrations determined via any of several nucleic acid quantitation methods using ultraviolet absorbance spectroscopy.

[96] The fully formed target structures can be verified using native gel electrophoresis, which gives size and shape information for the nucleic acid complexes.