Nebuchadnezzar II

Through this conquest, the subsequent capture of the Phoenician city of Tyre, and other campaigns in the Levant, Nebuchadnezzar restored the Neo-Babylonian Empire's fortunes in the ancient Near East.

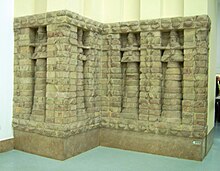

Beyond his military campaigns, Nebuchadnezzar is remembered as a great builder who erected many of Babylon's religious buildings, including the Esagila and Etemenanki, embellished its palaces and beautified its ceremonial centre through renovations to the city's processional street and the Ishtar Gate.

[15] As a result, historical reconstructions of this period generally follow secondary sources in Hebrew, Greek and Latin to determine what events transpired at the time, in addition to contract tablets from Babylonia.

The Assyriologist Adrianus van Selms suggested in 1974 that the variant with an "n" rather than an "r" was a rude nickname, deriving from an Akkadian rendition like Nabû-kūdanu-uṣur, which means 'Nabu, protect the mule', though there is no concrete evidence for this idea.

The war resulted in the complete destruction of Assyria,[23] and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which rose in its place, was powerful, but hastily built and politically unstable.

It is possible that he was a member of its ruling elite before becoming king[27] and there is a growing body of evidence that Nabopolassar's family originated in Uruk, for instance that Nebuchadnezzar's daughters lived in the city.

[2] In Assyrian tradition, the desecration of a dead body showed that the deceased individual and their surviving family were traitors and enemies of the state, and that they had to be completely eradicated, serving to punish them even after death.

[35] After the fall of Harran, Psamtik's successor, Pharaoh Necho II, personally led a large army into former Assyrian lands to turn the tide of the war and restore the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[36] even though it was more or less a lost cause as Assyria had already collapsed.

[38] Nebuchadnezzar's greatest victory from his time as crown prince came at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC,[32] which put an end to Necho's campaign in the Levant by inflicting a crushing defeat on the Egyptians.

It is possible to conclude, based on subsequent geopolitics, that the victory resulted in all of Syria and Israel coming under the control of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, a feat which the Assyrians under Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC) only accomplished after five years of protracted military campaigns.

Nabopolassar was laid in a huge coffin, adorned with ornamented gold plates and fine dresses with golden beads, which was then placed within a small palace he had constructed in Babylon.

Thus, a campaign against Egypt was logical in order to assert Babylonian dominance, and also carried enormous economic and propagandistic benefits, but it was also risky and ambitious.

[49]Jehoiakim had died during Nebuchadnezzar's siege and been replaced by his son, Jeconiah, who was captured and taken to Babylon, with his uncle Zedekiah installed in his place as king of Judah.

[49] In 597 BC, the Babylonian army departed for the Levant again, but appears to not have engaged in any military activities as they turned back immediately after reaching the Euphrates.

In 595 BC, Nebuchadnezzar stayed at home in Babylon but soon had to face a rebellion against his rule there, though he defeated the rebels, with the chronicle stating that the king "put his large army to the sword and conquered his foe."

According to the Assyriologist Israel Ephʿal, Babylon at this time was seen by its contemporaries more like a "paper tiger" (i. e. an ineffectual threat) than a great empire, like Assyria just a few decades prior.

It is possible that the intensity of the destruction carried out by Nebuchadnezzar at Jerusalem and elsewhere in the Levant was due to the implementation of something akin to a scorched earth-policy, aimed at stopping Egypt from gaining a foothold there.

[49] According to the Bible, and the 1st-century AD Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, Zedekiah attempted to flee after resisting the Babylonians, but was captured at Jericho and suffered a terrible fate.

[57] A stele from Tahpanhes uncovered in 2011 records that Nebuchadnezzar attempted to invade Egypt in 582 BC, although Apries' forces managed to repel the invasion.

[63] The supposed length of the siege can be ascribed to the difficulty in besieging the city: Tyre was located on an island 800 metres from the coast, and could not be taken without naval support.

[60] According to later Jewish tradition, it is possible that Ithobaal III was deposed and taken as a prisoner to Babylon, with another king, Baal II, proclaimed by Nebuchadnezzar in his place.

[74] Glazed bricks such as the ones used in the Procession Street were also used in the throne room of the South Palace, which was decorated with depictions of lions and tall, stylized palm trees.

[75] Other great building projects by Nebuchadnezzar include the Nar-Shamash, a canal to bring water from the Euphrates close to the city of Sippar, and the Median Wall, a large defensive structure built to defend Babylonia against incursions from the north.

[86] According to tradition, Nebuchadnezzar constructed the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, featuring exotic shrubs, vines and trees as well as artificial hills, watercourses and knolls, so that Amytis would feel less homesick for the mountains of Media.

Many Assyriologists, such as Wolfram von Soden in 1954, thus initially assumed that Nebuchadnezzar had mainly been a builder-king, devoting his energy and efforts to building and restoring his country.

From the publication of these tablets and onwards, historians have shifted to perceiving Nebuchadnezzar as a great warrior, devoting special attention to the military achievements of his reign.

[111] It is possible that the epithet is a later addition, as it is missing in the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, perhaps added after Nebuchadnezzar began to be seen in a slightly more favourable light than immediately after Jerusalem's destruction.

A second story again casts Nebuchadnezzar as a tyrannical and pagan king, who, after Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego refuse to worship a newly erected golden statue, sentences them to death through being thrown into a fiery furnace.

[124] Nebuchadnezzar is referred to as Buḫt Nuṣṣur (بخت نصر) in works of the mediaeval scholar al-Ṭabarī, where he is credited with conquering Egypt, Syria, Phoenicia and Arabia.

[125] In similar fashion Strabo, citing Megasthenes, mentioned in a list of mythical and semi-legendary conquerors, a Nabocodrosor as having led an army to the Pillars of Hercules and being revered by the Chaldaeans.