Interest rate

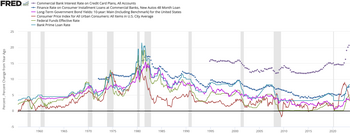

Interest rate targets are a vital tool of monetary policy and are taken into account when dealing with variables like investment, inflation, and unemployment.

[3][4][5][6][7] In the past two centuries, interest rates have been variously set either by national governments or central banks.

[10][11] During an attempt to tackle spiraling hyperinflation in 2007, the Central Bank of Zimbabwe increased interest rates for borrowing to 800%.

[13] Before modern capital markets, there have been accounts that savings deposits could achieve an annual return of at least 25% and up to as high as 50%.

The repayment of principal plus interest is measured in real terms compared against the buying power of the amount at the time it was borrowed, lent, deposited or invested.

Agents may exhibit myopia (limited attention) to certain economic variables, form expectations based on simplified heuristics, or update their beliefs more gradually than under full rationality.

The additional return above the risk-free nominal interest rate which is expected from a risky investment is the risk premium.

This preference creates a term structure of required returns, exemplified by the higher yields typically demanded for longer-duration assets.

However, the existence of deep secondary markets can partially mitigate illiquidity costs, as evidenced by US Treasury bonds, which maintain significant liquidity despite longer maturities due to their unique status as a safe asset and the associated financial sector stability benefits.

[21] Interest rates affect economic activity broadly, which is the reason why they are normally the main instrument of the monetary policies conducted by central banks.

Consequently, by influencing the general interest rate level, monetary policy can affect overall demand for goods and services in the economy and hence output and employment.

[25] However, since 2008 the actual conduct of monetary policy implementation has changed considerably, the Fed using instead various administered interest rates (i.e., interest rates that are set directly by the Fed rather than being determined by the market forces of supply and demand) as the primary tools to steer short-term market interest rates towards the Fed's policy target.

[28] From 1982 until 2012, most Western economies experienced a period of low inflation combined with relatively high returns on investments across all asset classes including government bonds.

In reality, the relationship is so The two approximations, eliminating higher order terms, are: The formulae in this article are exact if logarithmic units are used for relative changes, or equivalently if logarithms of indices are used in place of rates, and hold even for large relative changes.

At this zero lower bound the central bank faces difficulties with conventional monetary policy, because it is generally believed that market interest rates cannot realistically be pushed down into negative territory.

When this is done via government policy (for example, via reserve requirements), this is deemed financial repression, and was practiced by countries such as the United States and United Kingdom following World War II (from 1945) until the late 1970s or early 1980s (during and following the Post–World War II economic expansion).

[30][31] In the late 1970s, United States Treasury securities with negative real interest rates were deemed certificates of confiscation.

[33] Negative interest rates have been proposed in the past, notably in the late 19th century by Silvio Gesell.

[42][43] The Riksbank studied the impact of these changes and stated in a commentary report[44] that they led to no disruptions in Swedish financial markets.

During the European debt crisis, government bonds of some countries (Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and Austria) have been sold at negative yields.

[46] For practical purposes, investors and academics typically view the yields on government or quasi-government bonds guaranteed by a small number of the most creditworthy governments (United Kingdom, United States, Switzerland, EU, Japan) to effectively have negligible default risk.

As financial theory would predict, investors and academics typically do not view non-government guaranteed corporate bonds in the same way.

The most notable example of this was Nestle, some of whose AAA-rated bonds traded at negative nominal interest rate in 2015.