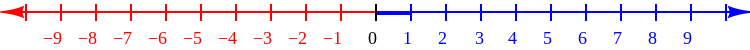

Negative number

If a quantity, such as the charge on an electron, may have either of two opposite senses, then one may choose to distinguish between those senses—perhaps arbitrarily—as positive and negative.

Negative numbers were used in the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, which in its present form dates from the period of the Chinese Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), but may well contain much older material.

[3] Liu Hui (c. 3rd century) established rules for adding and subtracting negative numbers.

[4] By the 7th century, Indian mathematicians such as Brahmagupta were describing the use of negative numbers.

[6] Western mathematicians like Leibniz held that negative numbers were invalid, but still used them in calculations.

However, it can lead to confusion and be difficult for a person to understand an expression when operator symbols appear adjacent to one another.

In this case, losing two debts of three each is the same as gaining a credit of six: The convention that a product of two negative numbers is positive is also necessary for multiplication to follow the distributive law.

We can extend addition and multiplication to these pairs with the following rules: We define an equivalence relation ~ upon these pairs with the following rule: This equivalence relation is compatible with the addition and multiplication defined above, and we may define Z to be the quotient set N²/~, i.e. we identify two pairs (a, b) and (c, d) if they are equivalent in the above sense.

The additive inverse of a number is unique, as is shown by the following proof.

For a long time, understanding of negative numbers was delayed by the impossibility of having a negative-number amount of a physical object, for example "minus-three apples", and negative solutions to problems were considered "false".

In Hellenistic Egypt, the Greek mathematician Diophantus in the 3rd century AD referred to an equation that was equivalent to

[24] For this reason Greek geometers were able to solve geometrically all forms of the quadratic equation which give positive roots, while they could take no account of others.

[25] Negative numbers appear for the first time in history in the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (九章算術, Jiǔ zhāng suàn-shù), which in its present form dates from the Han period, but may well contain much older material.

[3] The mathematician Liu Hui (c. 3rd century) established rules for the addition and subtraction of negative numbers.

[4] The Chinese were able to solve simultaneous equations involving negative numbers.

Liu Hui writes: Now there are two opposite kinds of counting rods for gains and losses, let them be called positive and negative.

The Indian mathematician Brahmagupta, in Brahma-Sphuta-Siddhanta (written c. AD 630), discussed the use of negative numbers to produce a general form quadratic formula similar to the one in use today.

[24] In the 9th century, Islamic mathematicians were familiar with negative numbers from the works of Indian mathematicians, but the recognition and use of negative numbers during this period remained timid.

[5] But within fifty years, Abu Kamil illustrated the rules of signs for expanding the multiplication

,[31] and al-Karaji wrote in his al-Fakhrī that "negative quantities must be counted as terms".

[5] In the 10th century, Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī considered debts as negative numbers in A Book on What Is Necessary from the Science of Arithmetic for Scribes and Businessmen.

[31] By the 12th century, al-Karaji's successors were to state the general rules of signs and use them to solve polynomial divisions.

[5]In the 12th century in India, Bhāskara II gave negative roots for quadratic equations but rejected them because they were inappropriate in the context of the problem.

Fibonacci allowed negative solutions in financial problems where they could be interpreted as debits (chapter 13 of Liber Abaci, 1202) and later as losses (in Flos, 1225).

In 1545, Gerolamo Cardano, in his Ars Magna, provided the first satisfactory treatment of negative numbers in Europe.

[24] He did not allow negative numbers in his consideration of cubic equations, so he had to treat, for example,

In all, Cardano was driven to the study of thirteen types of cubic equations, each with all negative terms moved to the other side of the = sign to make them positive.