Neuroscience of free will

[citation needed] Other studies have attempted to predict the actions of participants before they happen,[6][7] explore how we know we are responsible for voluntary movements as opposed to being moved by an external force,[8] or how the role of consciousness in decision-making may differ depending on the type of decision being made.

[18] Particularly in earlier studies, research relied on self-reported measures of conscious awareness, but introspective estimates of event timing were found to be biased or inaccurate in some cases.

[19] Researcher Itzhak Fried says that available studies do at least suggest that consciousness comes in a later stage of decision-making than previously expected – challenging any versions of "free will" where intention occurs at the beginning of the human decision process.

[21] In contrast to this claim, neuroscientist Walter Jackson Freeman III, discusses the impact of unconscious systems and actions to change the world according to human intention.

Some thinkers like neuroscientist and philosopher Adina Roskies think that these studies can still only show, unsurprisingly, that physical factors in the brain are involved before decision-making.

This issue may be controversial for good reason: there is evidence to suggest that people normally associate a belief in free will with their ability to affect their lives.

[3][4] Philosopher Daniel Dennett, author of Elbow Room and a supporter of deterministic free will, believes that scientists risk making a serious mistake.

[24] The other studies described below have only just begun to shed light on the role that consciousness plays in actions, and it is too early to draw very strong conclusions about certain kinds of "free will".

[35][36][37] A pioneering experiment in this field was conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s, in which he asked each subject to choose a random moment to flick their wrist while he measured the associated activity in their brain (in particular, the build-up of electrical signal called the Bereitschaftspotential (BP), which was discovered by Kornhuber & Deecke in 1965[38]).

However, findings from this study show that W in fact shifts systematically with the time of the tone presentation, implicating that W is, at least in part, retrospectively reconstructed rather than pre-determined by the Bereitschaftspotential.

[49] A study conducted by Jeff Miller and Judy Trevena (2010) suggests that the Bereitschaftspotential (BP) signal in Libet's experiments doesn't represent a decision to move, but that it's merely a sign that the brain is paying attention.

[56] According to this model, unconscious impulses to perform a volitional act are open to suppression by the conscious efforts of the subject (sometimes referred to as "free won't").

[57] A 2011 study conducted by Itzhak Fried found with a greater than 80% accuracy that individual neurons fire 700 ms before a reported "will" to act (long before EEG activity predicted such a response).

[16] Similarly to these tests, Chun Siong Soon, Anna Hanxi He, Stefan Bode and John-Dylan Haynes have conducted a study in 2013 claiming to be able to predict by 4 s the choice to sum or subtract before the subject reports it.

[58] William R. Klemm pointed out the inconclusiveness of these tests due to design limitations and data interpretations and proposed less ambiguous experiments,[18] while affirming a stand on the existence of free will[59] like Roy F. Baumeister[60] or Catholic neuroscientists such as Tadeusz Pacholczyk.

[63] In a study published in 2012, Aaron Schurger, Jacobo D. Sitt, and Stanislas Dehaene published in PNAS proposed that the occurrence of the readiness potentials observed in Libet-type experiments is stochastically occasioned by ongoing spontaneous subthreshold fluctuations in neural activity, rather than an unconscious goal-directed operation,[64][65][66] and challenged assumptions about the causal nature of the Bereitschaftspotential itself (and the "pre-movement buildup" of neural activity in general when faced with a choice), thus denying the conclusions drawn from studies such as Libet's[39] and Fried's.

A study by Masao Matsuhashi and Mark Hallett, published in 2008, claims to have replicated Libet's findings without relying on subjective report or clock memorization on the part of participants.

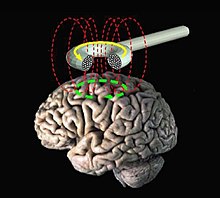

The last step of the experiment is to compare time T for each subject with their event-related potential (ERP) measures (e.g., seen in this page's lead image), which reveal when their finger movement genesis first begins.

Testing the hypothesis that "conscious intention occurs after movement genesis has already begun" required the researchers to analyse the distribution of responses to tones before actions.

Due to the varying delays, this was sometimes impossible (e.g., some decide signals simply appeared too late in the process of them both intending to and pressing the go button for them to be obeyed).

Libet tells when the readiness potential occurs objectively, using electrodes, but relies on the subject reporting the position of the hand of a clock to determine when the conscious decision was made.

fMRI machine learning of brain activity (multivariate pattern analysis) has been used to predict the user choice of a button (left/right) up to 7 seconds before their reported will of having done so.

[6] Another version of the fMRI multivariate pattern analysis experiment was conducted using an abstract decision problem, in an attempt to rule out the possibility of the prediction capabilities being product of capturing a built-up motor urge.

The participant first chose in their mind whether they wished to perform an addition or subtraction operation, and noted the central letter on the screen at the time of this decision.

The prediction capacities of the Chun Siong Soon et al. (2008) experiment were successfully replicated using a linear SVM model based on participant decision history alone (without any brain activity data).

In particular, the prediction of considered judgements from brain activity involving thought processes beginning minutes rather than seconds before a conscious will to act, including the rejection of a conflicting desire.

[91] In late 2015, following a previous 2010 study,[92] both based on earlier investigations on both monkeys and humans, a team of researchers from the UK and the US published an article demonstrating similar findings.

Studies have focused on the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA) of the brain, in which readiness potential indicating the beginning of a movement genesis has been recorded by EEG.

That ability would seem to be at odds with epiphenomenalism, which, according to Thomas Henry Huxley, is the broad claim that consciousness is "completely without any power… as the steam-whistle which accompanies the work of a locomotive engine is without influence upon its machinery".

[104][105] Seligman and others argue that free will and the role of subjectivity in consciousness can be better understood by taking such a "prospective" stance on cognition and that "accumulating evidence in a wide range of research suggests [this] shift in framework".