Nuclear force

This energy is stored when the protons and neutrons are bound together by the nuclear force to form a nucleus.

For identical nucleons (such as two neutrons or two protons) this repulsion arises from the Pauli exclusion force.

A Pauli repulsion also occurs between quarks of the same flavour from different nucleons (a proton and a neutron).

But if the particles' spins are anti-aligned, the nuclear force is too weak to bind them, even if they are of different types.

To disassemble a nucleus into unbound protons and neutrons requires work against the nuclear force.

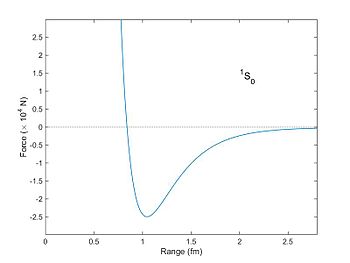

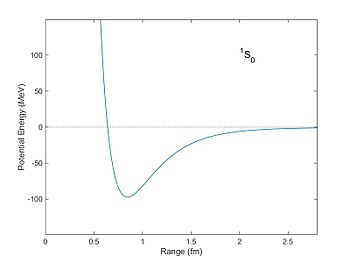

The force depends on whether the spins of the nucleons are parallel or antiparallel, as it has a non-central or tensor component.

The symmetry resulting in the strong force, proposed by Werner Heisenberg, is that protons and neutrons are identical in every respect, other than their charge.

In other words, both isospin and intrinsic spin transformations are isomorphic to the SU(2) symmetry group.

There are only strong attractions when the total isospin of the set of interacting particles is 0, which is confirmed by experiment.

[7] Our understanding of the nuclear force is obtained by scattering experiments and the binding energy of light nuclei.

The weak force plays no role in the interaction of nucleons, though it is responsible for the decay of neutrons to protons and vice versa.

Within months after the discovery of the neutron, Werner Heisenberg[8][9][10] and Dmitri Ivanenko[11] had proposed proton–neutron models for the nucleus.

The liquid-drop model treated the nucleus as a drop of incompressible nuclear fluid, with nucleons behaving like molecules in a liquid.

The model was first proposed by George Gamow and then developed by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker.

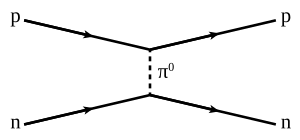

In 1934, Hideki Yukawa made the earliest attempt to explain the nature of the nuclear force.

In light of quantum chromodynamics (QCD)—and, by extension, the Standard Model—meson theory is no longer perceived as fundamental.

But the meson-exchange concept (where hadrons are treated as elementary particles) continues to represent the best working model for a quantitative NN potential.

Throughout the 1930s a group at Columbia University led by I. I. Rabi developed magnetic-resonance techniques to determine the magnetic moments of nuclei.

The discovery meant that the physical shape of the deuteron was not symmetric, which provided valuable insight into the nature of the nuclear force binding nucleons.

[1] Hans Bethe identified the discovery of the deuteron's quadrupole moment as one of the important events during the formative years of nuclear physics.

The strong interaction is the attractive force that binds the elementary particles called quarks together to form the nucleons (protons and neutrons) themselves.

Two-nucleon systems such as the deuteron, the nucleus of a deuterium atom, as well as proton–proton or neutron–proton scattering are ideal for studying the NN force.

The parameters of the potential are determined by fitting to experimental data such as the deuteron binding energy or NN elastic scattering cross sections (or, equivalently in this context, so-called NN phase shifts).

A more recent approach is to develop effective field theories for a consistent description of nucleon–nucleon and three-nucleon forces.

Additionally, chiral symmetry breaking can be analyzed in terms of an effective field theory (called chiral perturbation theory) which allows perturbative calculations of the interactions between nucleons with pions as exchange particles.

There are two major obstacles to overcome: This is an active area of research with ongoing advances in computational techniques leading to better first-principles calculations of the nuclear shell structure.

A successful way of describing nuclear interactions is to construct one potential for the whole nucleus instead of considering all its nucleon components.