Early Christian art and architecture

[3][4][5] Early Christian art and architecture adapted Roman artistic motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols.

Early Christian art is generally divided into two periods by scholars: before and after either the Edict of Milan of 313, bringing the so-called Triumph of the Church under Constantine, or the First Council of Nicea in 325.

Initially Jesus was represented indirectly by pictogram symbols such as the Ichthys (fish), peacock, Lamb of God, or an anchor (the Labarum or Chi-Rho was a later development).

Later personified symbols were used, including Jonah, whose three days in the belly of the whale pre-figured the interval between the death and resurrection of Jesus, Daniel in the lion's den, or Orpheus' charming the animals.

The "almost total absence from Christian monuments of the period of persecutions of the plain, unadorned cross" except in the disguised form of the anchor,[8] is notable.

It may also have been the case that the painted chambers in the catacombs were decorated in similar style to the best rooms of the homes of the better-off families buried in them, with Christian scenes and symbols replacing those from mythology, literature, paganism and eroticism, although we lack the evidence to confirm this.

There was a preference for what are sometimes called "abbreviated" representations, small groups of say one to four figures forming a single motif which could be easily recognised as representing a particular incident.

These vignettes fitted the Roman style of room decoration, set in compartments in a scheme with a geometrical structure (see gallery below).

[21] Biblical scenes of figures rescued from mortal danger were very popular; these represented both the Resurrection of Jesus, through typology, and the salvation of the soul of the deceased.

Jonah and the whale,[22][23] the Sacrifice of Isaac, Noah praying in the Ark (represented as an orant in a large box, perhaps with a dove carrying a branch), Moses striking the rock, Daniel in the lion's den and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace ([24]) were all favourites, that could be easily depicted.

[25][26][21][27][28] Early Christian sarcophagi were a much more expensive option, made of marble and often heavily decorated with scenes in very high relief, worked with drills.

A variety of different types of appearance were used, including the thin long-faced figure with long centrally-parted hair that was later to become the norm.

But in the earliest images as many show a stocky and short-haired beardless figure in a short tunic, who can only be identified by his context.

Pagan temples remained in use for their original purposes for some time and, at least in Rome, even when deserted were shunned by Christians until the 6th or 7th centuries, when some were converted to churches.

The usable model at hand, when Emperor Constantine I wanted to memorialize his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilica.

There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a center nave with one aisle at each side, and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other.

All variations allowed natural light from windows high in the walls, a departure from the windowless sanctuaries of the temples of most previous religions, and this has remained a consistent feature of Christian church architecture.

Formulas giving churches with a large central area were to become preferred in Byzantine architecture, which developed styles of basilica with a dome early on.

[37] A particular and short-lived type of building, using the same basilican form, was the funerary hall, which was not a normal church, though the surviving examples long ago became regular churches, and they always offered funeral and memorial services, but a building erected in the Constantinian period as an indoor cemetery on a site connected with early Christian martyrs, such as a catacomb.

The six examples built by Constantine outside the walls of Rome are: Old Saint Peter's Basilica, the older basilica dedicated to Saint Agnes of which Santa Costanza is now the only remaining element, San Sebastiano fuori le mura, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano, and one in the modern park of Villa Gordiani.

By the end of the period the style of using a gold ground had developed that continued to characterize Byzantine images, and many medieval Western ones.

These can be compared to the paintings of Dura-Europos, and probably also derive from a lost tradition of both Jewish and Christian illustrated manuscripts, as well as more general Roman precedents.

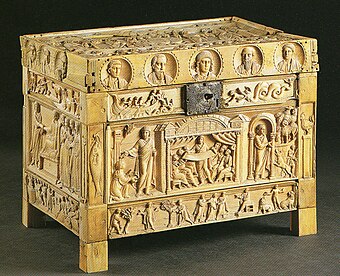

A number of ivory carvings have survived, including the complex late-5th-century Brescia Casket, probably a product of Saint Ambrose's episcopate in Milan, then the seat of the Imperial court, and the 6th-century Throne of Maximian from the Byzantine Italian capital of Ravenna.

There are a very fewer larger designs, but the great majority of the around 500 survivals are roundels that are the cut-off bottoms of wine cups or glasses used to mark and decorate graves in the Catacombs of Rome by pressing them into the mortar.