Pan-Germanism

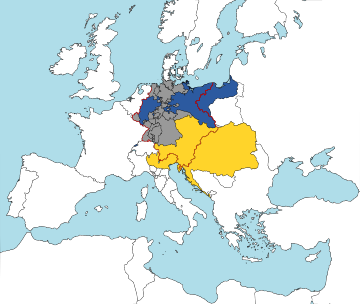

From the late 19th century, many Pan-Germanist thinkers, since 1891 organized in the Pan-German League, had adopted openly ethnocentric and racist ideologies, and ultimately gave rise to the foreign policy Heim ins Reich pursued by Nazi Germany under Austrian-born Adolf Hitler from 1938, one of the primary factors leading to the outbreak of World War II.

For example adjectives such as "alldeutsch" or "gesamtdeutsch", which can be translated as "pan-german", typically refer to the Alldeutsche Bewegung, a political movement which sought to unite all German speaking people in one country,[5] whereas "Pangermanismus" can refer to both the pursuit of uniting all the German-speaking people and movements which sought to unify all speakers of Germanic languages.

[6] The origins of Pan-Germanism began with the birth of Romantic nationalism during the Napoleonic Wars, with Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Ernst Moritz Arndt being early proponents.

Germans, for the most part, had been a loose and disunited people since the Reformation, when the Holy Roman Empire was shattered into a patchwork of states following the end of the Thirty Years' War with the Peace of Westphalia.

The Austrian Empire—like the Holy Roman Empire—was a multi-ethnic state, but the German-speaking people there did not have an absolute numerical majority; its re-shaping into the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one result of the growing nationalism of other ethnicities—especially the Hungarians.

Under Prussian leadership, Otto von Bismarck would ride on the coat-tails of nationalism to unite all of the northern German lands.

[10] The most radical Austrian pan-German Georg Schönerer (1842–1921) and Karl Hermann Wolf (1862–1941) articulated Pan-Germanist sentiments in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Munich professor Karl Haushofer, Ewald Banse, and Hans Grimm (author of the novel Volk ohne Raum) preached similar expansionist policies.

[18] After the end of Nazi Germany and the events of World War II in 1945, the ideas of pan-Germanism and an Anschluss fell out of favour due to their association with Nazism and allowed Austrians to develop their own national identity.

Nevertheless, such notions were revived with the German national camp in the Federation of Independents and the early Freedom Party of Austria.

[21] Jacob Grimm adopted Munch's anti-Danish Pan-Germanism and argued that the entire peninsula of Jutland had been populated by Germans before the arrival of the Danes and that thus it could justifiably be reclaimed by Germany, whereas the rest of Denmark should be incorporated into Sweden.

This line of thinking was countered by Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, an archaeologist who had excavated parts of Danevirke, who argued that there was no way of knowing the language of the earliest inhabitants of Danish territory.

Prominent supporters included Peter Andreas Munch, Christopher Bruun, Knut Hamsun, Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.

[28] Following the defeat in World War I, the influence of German-speaking elites over Central and Eastern Europe was greatly limited.

[30] Different aspects of the legacy of this medieval empire in German history were both celebrated and derided by the Nazi government.

Hitler admired the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne for his "cultural creativity", his powers of organization, and his renunciation of the rights of the individual.

[30] He criticized the Holy Roman Emperors however for not pursuing an Ostpolitik (Eastern Policy) resembling his own, while being politically focused exclusively on the south.

[35] Final solution Pre-Machtergreifung Post-Machtergreifung Parties The Heim ins Reich ("Back Home to the Reich") initiative was a policy pursued by the Nazis which attempted to convince the ethnic Germans living outside of Nazi Germany (such as in Austria and Sudetenland) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a Greater Germany.

They were deemed of vital interest for the survival of the German nation, as it was a core tenet of Nazi ideology that it needed "living space" (Lebensraum), creating a "pull towards the East" (Drang nach Osten) where that could be found and colonized, in a model that the Nazis explicitly derived from the American Manifest Destiny in the Far West and its clearing of native inhabitants.

[citation needed] The Waffen-SS was to be the eventual nucleus of a common European army where each state would be represented by a national contingent.

The scale of the Germans' defeat was unprecedented; Pan-Germanism became taboo because it had been tied to racist concepts of the "master race" and Nordicism by the Nazi party.