Parthian art

They depict men and women in robes, richly decorated with numerous jewels, and often represent the ruins of a city often associated with romantic literary sources in conjunction with Queen Zenobia.

The classical archaeologist and director of the excavations, Michael Rostovtzeff, realized that the art of the first centuries AD in Palmyra, Dura Europos, and also in Iran and its other territories followed the same principles.

The Parthian empire stretched over a vast area that was congruent mainly with the territory of present-day Iran and Iraq, and many different tribes.

An example are the coins of Vonones I (6-12 AD), the specimens that were minted in Seleucia show a purely Greek style.

There were purely Greek marble sculptures and a series of ivory rhytons in Hellenistic style with figuratively decorated designs.

The style of the figures is purely Hellenistic, even if the characters are a bit rough and some topics from the Greek stories shown were apparently not always understood.

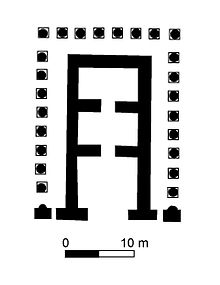

The square house in Nisa is 38×38 meters in size and consists of a large courtyard which is decorated on all four sides by columns.

The proportions of individual components (pillars seem to be long and thin) suggest that this house had no purely Greek architect.

The earliest specimens are difficult to determine, but are certainly in the Greek style, even if the Parthian rulers carry attributes, which gives the coin an amalgamated appearance.

[17] In the year 31 AD, a stele dating from Dura-Europos, which shows the god Zeus Kyrios consecrating Seleucus I Nicator was erected.

[19] The reliefs probably show myths, but their content is unknown from written sources, so that the representations can only be interpreted visually and thus remain incomprehensible.

[21] Therefore, it can be determined from around the 1st century in the Parthian Empire a new style, which is characterized mainly by severe frontal views of the figures, by a linearism and a hieratic representation, is observed.

Angular shapes replaced the round, flowing forms of the Greek style, at least more prevalently, on the profile on the coins.

However, there are virtually no examples of figurative wall paintings from the early stages of Parthian art, as it was still under Greek influence.

Many examples of Parthian period sculpture found in Palmyra, where the tombs of the local upper class were richly decorated, depict the lives of the deceased.

Sarcophagi decorated on the actual coffin box and lying on the lid of the deceased, usually on the side shown at a banquet.

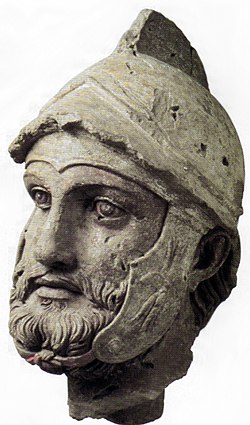

: Hatra in contrast, had numerous stone statues representing deities or local rulers and their family members.

[37] The most famous Parthian art work is the bronze statue of a local prince found in the Iranian province of Bachtiyārī at Shami.

According to the inscription it comes from the Charakene (a part of the Parthian Empire) around 150 AD as booty in the city and there adorned the Temple of Apollo.

Especially in southwest present-day Iran, in ancient Elymais, many rock reliefs were carved in open air sites in this style.

The rider probably represents a king, and has been identified as Mithridates I, who conquered Elymais in 140/139 BC when Parthian art was still largely Hellenistic.

[49] In architecture, there is a mixture of Greek and Oriental elements with new forms, especially as a remarkable new design with a large, open hall to a courtyard.

There are architecturally complex grave towers, which are also present at Dura Europos on the Euphrates, as well as at other places, but not in other parts of Syria.

[61][62] One of the most major finds for Parthian terracotta was at Seleucia on the Tigris where multiple, extremely detailed figures were found.

Astonishingly, there are both Greek and Oriental types present at the site, juxtaposing Parthian history in almost all eras in one spot.

The figures, gods and heroes, depicted frontally were not simple copies of life in a different material, they were instead meant to be viewed by the observer as alive.

While much of the better known Parthian art remained the same, because of its natural grandeur and transcendence, some are obvious symptoms of decline in the late 2nd century AD.

In large parts of Mesopotamia and Persia Parthian art simply disappeared, although certain artistic traditions, such as stucco reliefs and riding scenes, continued under the Sassanids.

Only with the fall of these cities (Hatra shortly after 240, Dura Europos at 256, Palmyra at 272) did Parthian art disappear from view.

In the Syrian and Armenian illuminations of the 6th to 10th centuries, however, many Parthian elements resurged that attest to a continued life of this style.