Pauson–Khand reaction

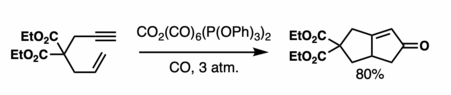

In it, an alkyne, an alkene, and carbon monoxide combine into a α,β-cyclopentenone in the presence of a metal-carbonyl catalyst[1] [2] Ihsan Ullah Khand (1935–1980) discovered the reaction around 1970, while working as a postdoctoral associate with Peter Ludwig Pauson (1925–2013) at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.

[6] The traditional reaction requires a stoichiometric amounts of dicobalt octacarbonyl, stabilized by a carbon monoxide atmosphere.

[8][9][10][11] While the mechanism has not yet been fully elucidated, Magnus' 1985 explanation[12] is widely accepted for both mono- and dinuclear catalysts, and was corroborated by computational studies published by Nakamura and Yamanaka in 2001.

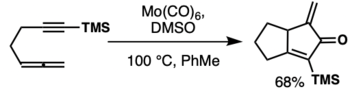

Typical Pauson-Khand conditions are elevated temperatures and pressures in aromatic hydrocarbon (benzene, toluene) or ethereal (tetrahydrofuran, 1,2-dichloroethane) solvents.

Adsorbing the metallic complex onto silica or alumina can enhance the rate of decarbonylative ligand exchange as exhibited in the image below.

[clarification needed] Additionally using a solid support restricts conformational movement (rotamer effect).

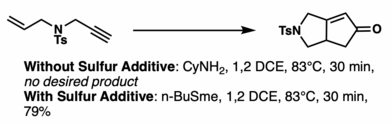

[20] Sulfur compounds are typically hard to handle and smelly, but n-dodecyl methyl sulfide[21] and tetramethylthiourea[22] do not suffer from those problems and can improve reaction performance.

It is believed that these additives remove carbon monoxide ligands via nucleophilic attack of the N-oxide onto the CO carbonyl, oxidizing the CO into CO2, and generating an unsaturated organometallic complex.

Density functional investigations show the variation arises from different transition state metal geometries.

[41] Heteroatoms are also acceptable: Mukai et al's total synthesis of physostigmine applied the Pauson–Khand reaction to a carbodiimide.

In addition to using a rhodium catalyst, this synthesis features an intramolecular cyclization that results in the normal 5-membered α,β-cyclopentenone as well as 7-membered ring.

- 1:

- Alkyne coordination , insertion and ligand dissociation to form an 18-electron complex ;

- 2:

- Ligand dissociation to form a 16-electron complex;

- 3:

- Alkene coordination to form an 18-electron complex;

- 4:

- Alkene insertion and ligand association ( synperiplanar , still 18 electrons);

- 5:

- CO migratory insertion;

- 6, 7:

- Reductive elimination of metal (loss of [Co 2 (CO) 6 ]);

- 8:

- CO association, to regenerate the active organometallic complex. [ 14 ]