Nonlinear optics

[1][2][3] The first nonlinear optical effect to be predicted was two-photon absorption, by Maria Goeppert Mayer for her PhD in 1931, but it remained an unexplored theoretical curiosity until 1961 and the almost simultaneous observation of two-photon absorption at Bell Labs[4] and the discovery of second-harmonic generation by Peter Franken et al. at University of Michigan, both shortly after the construction of the first laser by Theodore Maiman.

[5] These nonlinear interactions give rise to a host of optical phenomena: In these processes, the medium has a linear response to the light, but the properties of the medium are affected by other causes: Nonlinear effects fall into two qualitatively different categories, parametric and non-parametric effects.

Energy and momentum are conserved in the optical field, making phase matching important and polarization-dependent.

[15] [16] Parametric and "instantaneous" (i.e. material must be lossless and dispersionless through the Kramers–Kronig relations) nonlinear optical phenomena, in which the optical fields are not too large, can be described by a Taylor series expansion of the dielectric polarization density (electric dipole moment per unit volume) P(t) at time t in terms of the electric field E(t): where the coefficients χ(n) are the n-th-order susceptibilities of the medium, and the presence of such a term is generally referred to as an n-th-order nonlinearity.

In general, χ(n) is an (n + 1)-th-rank tensor representing both the polarization-dependent nature of the parametric interaction and the symmetries (or lack) of the nonlinear material.

Starting with Maxwell's equations in an isotropic space, containing no free charge, it can be shown that where PNL is the nonlinear part of the polarization density, and n is the refractive index, which comes from the linear term in P. Note that one can normally use the vector identity and Gauss's law (assuming no free charges,

As an example, if we consider only a second-order nonlinearity (three-wave mixing), then the polarization P takes the form If we assume that E(t) is made up of two components at frequencies ω1 and ω2, we can write E(t) as and using Euler's formula to convert to exponentials, where "c.c."

Typically, three-wave mixing is done in a birefringent crystalline material, where the refractive index depends on the polarization and direction of the light that passes through.

Most common nonlinear crystals are negative uniaxial, which means that the e axis has a smaller refractive index than the o axes.

Two other methods of phase matching avoid beam walk-off by forcing all frequencies to propagate at a 90° with respect to the optical axis of the crystal.

In this method the frequencies involved are not constantly locked in phase with each other, instead the crystal axis is flipped at a regular interval Λ, typically 15 micrometres in length.

This results in the polarization response of the crystal to be shifted back in phase with the pump beam by reversing the nonlinear susceptibility.

SHG of a pump and self-phase modulation (emulated by second-order processes) of the signal and an optical parametric amplifier can be integrated monolithically.

is nonzero, something that is generally true in any medium without any symmetry restrictions; in particular resonantly enhanced sum or difference frequency mixing in gasses is frequently used for extreme or "vacuum" ultra-violet light generation.

[19] In common scenarios, such as mixing in dilute gases, the non-linearity is weak and so the light beams are focused which, unlike the plane wave approximation used above, introduces a pi phase shift on each light beam, complicating the phase-matching requirements.

cancels this focal phase shift and often has a nearly self-canceling overall phase-matching condition, which relatively simplifies broad wavelength tuning compared to sum frequency generation.

[20] At even high intensities the Taylor series, which led the domination of the lower orders, does not converge anymore and instead a time based model is used.

High-order harmonic generation has been observed in noble gas jets, cells, and gas-filled capillary waveguides.

These crystals have the necessary properties of being strongly birefringent (necessary to obtain phase matching, see below), having a specific crystal symmetry, being transparent for both the impinging laser light and the frequency-doubled wavelength, and having high damage thresholds, which makes them resistant against the high-intensity laser light.

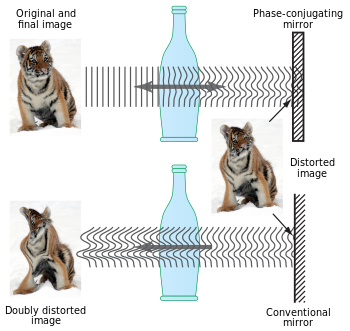

It is possible, using nonlinear optical processes, to exactly reverse the propagation direction and phase variation of a beam of light.

[25] Reversal of orbital angular momentum of optical vortex is due to the perfect match of helical phase profiles of the incident and reflected beams.

The most common way of producing optical phase conjugation is to use a four-wave mixing technique, though it is also possible to use processes such as stimulated Brillouin scattering.

The photon reflected from phase conjugating-mirror (out) has opposite directions of linear and angular momenta with respect to incident photon (in): Optical fields transmitted through nonlinear Kerr media can also display pattern formation owing to the nonlinear medium amplifying spatial and temporal noise.

[34] Examples of pattern formation are spatial solitons and vortex lattices in framework of nonlinear Schrödinger equation.

Due to the distinguished advantages, molecular nonlinear optics have been widely used in the biophotonics field, including bioimaging,[38][39] phototherapy,[40] biosensing,[41] etc.

Just as the polarizability can be described as a Taylor series expansion, one can expand the induced dipole moment in powers of the electric field:

These nonlinear materials, like multi-photon chromophores, are used as biomarkers for two-photon spectroscopy, in which the attenuation of incident light intensity as it passes through the sample is written as

[42] where N is the number of particles per unit volume, I is intensity of light, and δ is the two photon absorption cross section.

The resulting signal adopts a Lorentzian lineshape with a cross-section proportional to the difference in dipole moments of ground and final states.

Similar highly conjugated chromophores with strong donor-acceptor characteristics are used due to their large difference in the dipole moments, and current efforts in extending their pi-conjugated systems to enhance their nonlinear optical properties are being made.