Polish language

[24][25][26] Extensive usage of nonstandard dialects has also shaped the standard language; considerable colloquialisms and expressions were directly borrowed from German or Yiddish and subsequently adopted into the vernacular of Polish which is in everyday use.

The Book of Henryków (Polish: Księga henrykowska, Latin: Liber fundationis claustri Sanctae Mariae Virginis in Heinrichau), contains the earliest known sentence written in the Polish language: Day, ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai (in modern orthography: Daj, uć ja pobrusza, a ti pocziwaj; the corresponding sentence in modern Polish: Daj, niech ja pomielę, a ty odpoczywaj or Pozwól, że ja będę mełł, a ty odpocznij; and in English: Come, let me grind, and you take a rest), written around 1280.

[33] Tomasz Kamusella notes that "Polish is the oldest, non-ecclesiastical, written Slavic language with a continuous tradition of literacy and official use, which has lasted unbroken from the 16th century to this day.

Elsewhere, Poles constitute large minorities in areas which were once administered or occupied by Poland, notably in neighboring Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine.

In Ukraine, it is most common in the western parts of Lviv and Volyn Oblasts, while in West Belarus it is used by the significant Polish minority, especially in the Brest and Grodno regions and in areas along the Lithuanian border.

Most of the middle aged and young speak vernaculars close to standard Polish, while the traditional dialects are preserved among older people in rural areas.

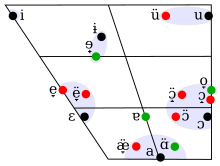

Unlike Czech or Slovak, Polish does not retain phonemic vowel length — the letter ó, which formerly represented lengthened /ɔː/ in older forms of the language, is now vestigial and instead corresponds to /u/.

A popular Polish tongue-twister (from a verse by Jan Brzechwa) is W Szczebrzeszynie chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinieⓘ [fʂt͡ʂɛbʐɛˈʂɨɲɛ ˈxʂɔw̃ʂt͡ʂ ˈbʐmi fˈtʂt͡ɕiɲɛ] ('In Szczebrzeszyn a beetle buzzes in the reed').

[73] These irregular stress patterns are explained by the fact that these endings are detachable clitics rather than true verbal inflections: for example, instead of kogo zobaczyliście?

The following digraphs and trigraphs are used: Voiced consonant letters frequently come to represent voiceless sounds (as shown in the tables); this occurs at the end of words and in certain clusters, due to the neutralization mentioned in the Phonology section above.

The exceptions to the above rule are certain loanwords from Latin, Italian, French, Russian or English—where s before i is pronounced as s, e.g. sinus, sinologia, do re mi fa sol la si do, Saint-Simon i saint-simoniści, Sierioża, Siergiej, Singapur, singiel.

Except in the cases mentioned above, the letter i if followed by another vowel in the same word usually represents /j/, yet a palatalization of the previous consonant is always assumed.

Latin was known to a larger or smaller degree by most of the numerous szlachta in the 16th to 18th centuries (and it continued to be extensively taught at secondary schools until World War II).

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Mongolian words were brought to the Polish language during wars with the armies of Genghis Khan and his descendants, e.g. dzida (spear) and szereg (a line or row).

[78] In 1518, the Polish king Sigismund I the Old married Bona Sforza, the niece of the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian, who introduced Italian cuisine to Poland, especially vegetables.

Examples include ekran (from French "écran", screen), abażur ("abat-jour", lamp shade), biuro ("bureau", office), biżuteria ("bijou", jewelry), rekin ("requin", shark), meble ("meuble", furniture), bagaż ("bagage", luggage), walizka ("valise", suitcase), fotel ("fauteuil", armchair), plaża ("plage", beach) and koszmar ("cauchemar", nightmare).

The regional dialects of Upper Silesia and Masuria (Modern Polish East Prussia) have noticeably more German loanwords than other varieties.

The contacts with Ottoman Turkey in the 17th century brought many new words, some of them still in use, such as: jar ("yar" deep valley), szaszłyk ("şişlik" shish kebab), filiżanka ("fincan" cup), arbuz ("karpuz" watermelon), dywan ("divan" carpet),[82] etc.

[85] The mountain dialects of the Górale in southern Poland, have quite a number of words borrowed from Hungarian (e.g. baca, gazda, juhas, hejnał) and Romanian as a result of historical contacts with Hungarian-dominated Slovakia and Wallachian herders who travelled north along the Carpathians.

[86] Thieves' slang includes such words as kimać (to sleep) or majcher (knife) of Greek origin, considered then unknown to the outside world.

[77] Recent loanwords come primarily from the English language, mainly those that have Latin or Greek roots, for example komputer (computer), korupcja (from 'corruption', but sense restricted to 'bribery') etc.

These include basic items, objects or terms such as a bread bun (Polish bułka, Yiddish בולקע bulke), a fishing rod (wędka, ווענטקע ventke), an oak (dąb, דעמב demb), a meadow (łąka, לאָנקע lonke), a moustache (wąsy, וואָנצעס vontses) and a bladder (pęcherz, פּענכער penkher).

During the Age of Enlightenment in Poland, Ignacy Krasicki, known as "the Prince of Poets", wrote the first Polish novel called The Adventures of Mr. Nicholas Wisdom as well as Fables and Parables.

Another significant work form this period is The Manuscript Found in Saragossa written by Jan Potocki, a Polish nobleman, Egyptologist, linguist, and adventurer.

In the Romantic Era, the most celebrated national poets, referred to as the Three Bards, were Adam Mickiewicz (Pan Tadeusz and Dziady), Juliusz Słowacki (Balladyna) and Zygmunt Krasiński (The Undivine Comedy).

Important positivist writers include Bolesław Prus (The Doll, Pharaoh), Henryk Sienkiewicz (author of numerous historical novels the most internationally acclaimed of which is Quo Vadis), Maria Konopnicka (Rota), Eliza Orzeszkowa (Nad Niemnem), Adam Asnyk and Gabriela Zapolska (The Morality of Mrs. Dulska).

The period known as Young Poland produced such renowned literary figures as Stanisław Wyspiański (The Wedding), Stefan Żeromski (Homeless People, The Spring to Come), Władysław Reymont (The Peasants) and Leopold Staff.

The prominent interbellum period authors include Maria Dąbrowska (Nights and Days), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Insatiability), Julian Tuwim, Bruno Schulz, Bolesław Leśmian, Witold Gombrowicz and Zuzanna Ginczanka.

Other notable writers and poets from Poland active during World War II and after are Aleksander Kamiński, Zbigniew Herbert, Stanisław Lem, Zofia Nałkowska, Tadeusz Borowski, Sławomir Mrożek, Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński, Julia Hartwig, Marek Krajewski, Joanna Bator, Andrzej Sapkowski, Adam Zagajewski, Dorota Masłowska, Jerzy Pilch, Ryszard Kapuściński and Andrzej Stasiuk.

Five people writing in the Polish language have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature: Henryk Sienkiewicz (1905), Władysław Reymont (1924), Czesław Miłosz (1980), Wisława Szymborska (1996) and Olga Tokarczuk (2018).