Political views on the Macedonian language

[2] Although Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of the Republic of Macedonia in 1991, most of its academics, as well as the general public, continue to regard the language spoken there as a form of Bulgarian.

However, after years of diplomatic impasse caused by this academic dispute, in 1999 the Bulgarian government settled the language issue by signing a Joint Declaration which used the euphemistic formulation: in Macedonian, pursuant to Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia, and in Bulgarian, pursuant the Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria.

In the interwar period, Macedonian was treated as a South Serbian dialect in Yugoslavia, in accordance with claims made in the 19th century.

[10] The 1940s saw opposing views on Macedonian in Bulgaria; while its existence was recognized in 1946-47 and allowed as the language of instruction in schools in Pirin Macedonia, the period after 1948 saw its rejection and restricted domestic use.

[16] Although Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of the Republic of Macedonia, most of its academics, as well as the general public, regarded the language spoken there as a form of Bulgarian.

[17] During Communist era Macedonian was recognized as a minority language in Bulgaria from 1946 to 1948, though, it was subsequently described again as a dialect or regional norm of Bulgarian.

[19] Nevertheless in the same year Bulgaria revoked finally its recognition of Macedonian nationhood and language and resumed implicitly its prewar position.

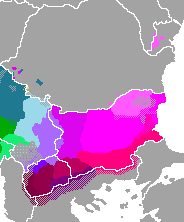

[23] The current international consensus outside of Bulgaria is that Macedonian is an autonomous language within the Eastern South Slavic dialect continuum.

[25] The Greek scientific and local community was opposed to using the denomination Macedonian to refer to the language in light of the Greek-Macedonian naming dispute.

Speakers themselves variously refer to their language as makedonski, makedoniski ("Macedonian"),[26] slaviká (Greek: σλαβικά, "Slavic"), dópia or entópia (Greek: εντόπια, "local/indigenous [language]"),[27] balgàrtzki (Bulgarian) or "Macedonian" in some parts of the region of Kastoria,[28] bògartski ("Bulgarian") in some parts of Dolna Prespa[16] along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old").

[31][32] For instance, the Croatian Bosnian researcher Stjepan Verković who was a long-term teacher in Macedonia sent by the Serbian government with a special assimilatory mission wrote in the preface of his collection of Bulgarian folk songs: "I named these songs Bulgarian, and not Slavic because today when you ask any Macedonian Slav: Who are you?

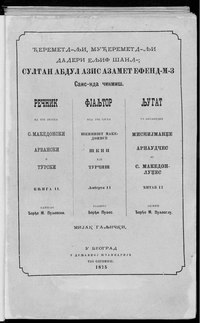

he immediately answers: I am Bulgarian and call my language Bulgarian…"[33] The name "Bulgarian" for various Macedonian dialects can be seen from early vernacular texts such as the four-language dictionary of Daniil of Moschopole, the early works of Kiril Pejchinovich and Ioakim Kurchovski and some vernacular gospels written in the Greek alphabet.

[35] In those early years the re-emerging Bulgarian written language was still heavily influenced by Church Slavonic forms so dialectical differences were not very prominent between the Eastern and Western regions.

This was to a large extent due to the fact that the wealthy towns on both sides of the Central Balkan range were able to produce more intellectuals educated in Europe than the relatively less developed other Bulgarian regions.

[37] In the article The Macedonian Question by Petko Rachev Slaveykov, published on 18 January 1871 in the Makedoniya newspaper in Constantinople, Macedonism was criticized, his adherents were named Macedonists, and this is the earliest surviving indirect reference to it, although Slaveykov never used the word Macedonism.The term's first recorded use is from 1887 by Stojan Novaković to describe Macedonism as a potential ally for the Serbian strategy to expand its territory toward Macedonia, whose population was regarded by almost all neutral sources as Bulgarian at the time.

All activists and leaders of the Macedonian movement, including those of the left, used standard Bulgarian in documents, press publications, correspondence and memoirs and nothing indicates they viewed it as a foreign language.

[39] From the 1930s onwards the Bulgarian Communist Party and the Comintern sought to foster a separate Macedonian nationality and language as a means of achieving autonomy for Macedonia within a Balkan federation.

[40][41] When Socialist Macedonia was formed as part of Federal Yugoslavia, these Bulgarian-trained cadres got into a conflict over the language with the more Serbian-leaning activists, who had been working within the Yugoslav Communist Party.

Since the latter held most of the political power, they managed to impose their views on the direction the new language was to follow, much to the dismay of the former group.

[43] After 1944 the communist-dominated government sought to create a Bulgarian-Yugoslav Balkan Communist Federation and part of this entailed giving "cultural autonomy" to the Pirin region.

[44] From January 1945 the regional newspaper Pirinsko Delo printed in Bulgaria started to publish a page in Macedonian.

Although Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of the Republic of Macedonia, most of its academics, as well as the general public, regard the language spoken there as a form of Bulgarian.

[57] They are also said to have resorted to falsifications and deliberate misinterpretations of history and documents in order to further the claim that there was a consciousness of a separate Macedonian ethnicity before 1944.

[66] Demetrius Andreas Floudas, Senior Associate of Hughes Hall, Cambridge, explains that it was only in 1944 that Josip Broz Tito, in order to increase his regional influence, gave to the southernmost province of Yugoslavia (officially known as Vardarska banovina under the banate regional nomenclature) the new name of People's Republic of Macedonia.

[71][72] New Democracy denied these claims, noting that the 1977 UN document states clearly that the terminology used thereof (i.e. the characterization of the languages) does not imply any opinion of the General Secretariat of the UN regarding the legal status of any country, territory, borders etc.

[73] On 12 June 2018, North Macedonia's Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, announced that the recognition of Macedonian by Greece is reaffirmed in the Prespa agreement.

[76] Horace Lunt wrote: "Bulgarian scholars, who argue that the concept of a Macedonian language was unknown before World War II, or who continue to claim that a Macedonian language does not exist look not only dishonest, but silly, while Greek scholars who make similar claims are displaying arrogant ignorance of their Slavic neighbours".

"The Greek Helsinki Monitor reports: "... the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness.

Standard Macedonian is based on the Western Macedonian dialects , consisting of the 'Western' and 'Central Macedonian' subgroups.