Salt (chemistry)

Salts composed of small ions typically have high melting and boiling points, and are hard and brittle.

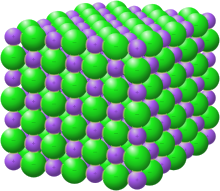

[2][3][4] This revealed that there were six equidistant nearest-neighbours for each atom, demonstrating that the constituents were not arranged in molecules or finite aggregates, but instead as a network with long-range crystalline order.

[4] These compounds were soon described as being constituted of ions rather than neutral atoms, but proof of this hypothesis was not found until the mid-1920s, when X-ray reflection experiments (which detect the density of electrons), were performed.

[4][5] Principal contributors to the development of a theoretical treatment of ionic crystal structures were Max Born, Fritz Haber, Alfred Landé, Erwin Madelung, Paul Peter Ewald, and Kazimierz Fajans.

[12] Alternately the counterions can be chosen to ensure that even when combined into a single solution they will remain soluble as spectator ions.

[8] Other synthetic routes use a solid precursor with the correct stoichiometric ratio of non-volatile ions, which is heated to drive off other species.

[23][24] Conversely, covalent bonds between unlike atoms often exhibit some charge separation and can be considered to have a partial ionic character.

[22] The circumstances under which a compound will have ionic or covalent character can typically be understood using Fajans' rules, which use only charges and the sizes of each ion.

[26][27] This difference in electronegativities means that the charge separation, and resulting dipole moment, is maintained even when the ions are in contact (the excess electrons on the anions are not transferred or polarized to neutralize the cations).

[34][35] Depending on the stoichiometry of the salt, and the coordination (principally determined by the radius ratio) of cations and anions, a variety of structures are commonly observed,[36] and theoretically rationalized by Pauling's rules.

[55] Schottky defects consist of one vacancy of each type, and are generated at the surfaces of a crystal,[54] occurring most commonly in compounds with a high coordination number and when the anions and cations are of similar size.

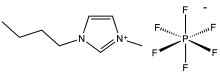

Some substances with larger ions, however, have a melting point below or near room temperature (often defined as up to 100 °C), and are termed ionic liquids.

[64] Ions in ionic liquids often have uneven charge distributions, or bulky substituents like hydrocarbon chains, which also play a role in determining the strength of the interactions and propensity to melt.

[65] Even when the local structure and bonding of an ionic solid is disrupted sufficiently to melt it, there are still strong long-range electrostatic forces of attraction holding the liquid together and preventing ions boiling to form a gas phase.

[68] As the temperature is elevated (usually close to the melting point) a ductile–brittle transition occurs, and plastic flow becomes possible by the motion of dislocations.

[73] There are some unusual salts such as cerium(III) sulfate, where this entropy change is negative, due to extra order induced in the water upon solution, and the solubility decreases with temperature.

Although they contain charged atoms or clusters, these materials do not typically conduct electricity to any significant extent when the substance is solid.

[13] The anions in compounds with bonds with the most ionic character tend to be colorless (with an absorption band in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum).

[81] In compounds with less ionic character, their color deepens through yellow, orange, red, and black (as the absorption band shifts to longer wavelengths into the visible spectrum).

[81] This occurs during hydration of metal ions, so colorless anhydrous salts with an anion absorbing in the infrared can become colorful in solution.

[dubious – discuss][clarification needed] Similarly, inorganic pigments tend not to be salts, because insolubility is required for fastness.

That slow, partial decomposition is usually accelerated by the presence of water, since hydrolysis is the other half of the reversible reaction equation of formation of weak salts.

[82] Humans have processed common salt (sodium chloride) for over 8000 years, using it first as a food seasoning and preservative, and now also in manufacturing, agriculture, water conditioning, for de-icing roads, and many other uses.

Examples of this include borax, calomel, milk of magnesia, muriatic acid, oil of vitriol, saltpeter, and slaked lime.

The concentration of solutes affects many colligative properties, including increasing the osmotic pressure, and causing freezing-point depression and boiling-point elevation.

[86] The increased ionic strength reduces the thickness of the electrical double layer around colloidal particles, and therefore the stability of emulsions and suspensions.

[91] These electrons later return to lower energy states, and release light with a colour spectrum characteristic of the species present.

[95] To obtain the elemental materials, these ores are processed by smelting or electrolysis, in which redox reactions occur (often with a reducing agent such as carbon) such that the metal ions gain electrons to become neutral atoms.

[98] In the most simple case of a binary salt with no possible ambiguity about the charges and thus the stoichiometry, the common name is written using two words.

[108] Because of the risk of ambiguity in allocating oxidation states, IUPAC prefers direct indication of the ionic charge numbers.