Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

[1] The Brotherhood was only ever a loose association and their principles were shared by other artists of the time, including Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes and Marie Spartali Stillman.

The Brotherhood believed the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art, hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite".

To the Pre-Raphaelites, according to William Michael Rossetti, "sloshy" meant "anything lax or scamped in the process of painting ... and hence ... any thing or person of a commonplace or conventional kind".

The Pre-Raphaelites defined themselves as a reform movement, created a distinct name for their form of art, and published a periodical, The Germ, to promote their ideas.

Hunt and Millais were students at the Royal Academy of Arts and had met in another loose association, the Cyclographic Club, a sketching society.

[7] Ford Madox Brown was invited to join, but the more senior artist remained independent but supported the group throughout the PRB period of Pre-Raphaelitism and contributed to The Germ.

The split was never absolute, since both factions believed that art was essentially spiritual in character, opposing their idealism to the materialist realism associated with Courbet and Impressionism.

Their emphasis on brilliance of colour was a reaction to the excessive use of bitumen by earlier British artists, such as Reynolds, David Wilkie and Benjamin Robert Haydon.

In 1848, Rossetti and Hunt made a list of "Immortals", artistic heroes whom they admired, especially from literature, some of whose work would form subjects for PRB paintings, notably including Keats and Tennyson.

(Daly 1989) In 1850, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood became the subject of controversy after the exhibition of Millais' painting Christ in the House of His Parents was considered to be blasphemous by many reviewers, notably Charles Dickens.

[12] According to Dickens, Millais made the Holy Family look like alcoholics and slum-dwellers, adopting contorted and absurd "medieval" poses.

The remaining members met to discuss whether he should be replaced by Charles Allston Collins or Walter Howell Deverell, but were unable to make a decision.

[14] The brotherhood found support from the critic John Ruskin, who praised its devotion to nature and rejection of conventional methods of composition.

They stressed the realist and scientific aspects of the movement, though Hunt continued to emphasise the spiritual significance of art, seeking to reconcile religion and science by making accurate observations and studies of locations in Egypt and Palestine for his paintings on biblical subjects.

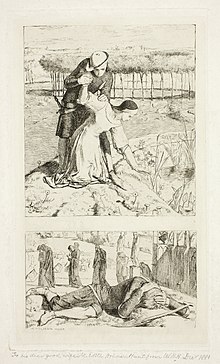

[23] Joseph Noel Paton (1821–1901) studied at the Royal Academy schools in London, where he became a friend of Millais and he subsequently followed him into Pre-Raphaelitism, producing pictures that stressed detail and melodrama such as The Bludie Tryst (1855).

After the First World War, Pre-Raphaelite art was devalued for its literary qualities[29] and was scorned by critics as sentimental and concocted "artistic bric-a-brac".

[32] In the late 20th century the Brotherhood of Ruralists based its aims on Pre-Raphaelitism, while the Stuckists and the Birmingham Group have also derived inspiration from it.

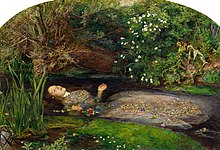

Many members of the 'inner' Pre-Raphaelite circle (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones) and 'outer' circle (Frederick Sandys, Arthur Hughes, Simeon Solomon, Henry Hugh Armstead, Joseph Noel Paton, Frederic Shields, Matthew James Lawless) were working concurrently in painting, illustration, and sometimes poetry.

"[34] Robert Buchanan (a writer and opponent of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) felt so strongly about this artistic hierarchy that he wrote: "The truth is that literature, and more particularly poetry, is in a very bad way when one art gets hold of another, and imposes upon it its conditions and limitations.

Their belief that each picture should tell a story was an important step for the unification of painting and literature (eventually deemed the Sister Arts[36]), or at least a break in the rigid hierarchy promoted by writers like Robert Buchanan.

"[37] This passage makes apparent Rossetti's desire to not just support the poet's narrative, but to create an allegorical illustration that functions separately from the text as well.

The Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico also has a notable collection of Pre-Raphaelite works, including Sir Edward Burne-Jones' The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon, Frederic Lord Leighton's Flaming June, and works by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Frederic Sandys.

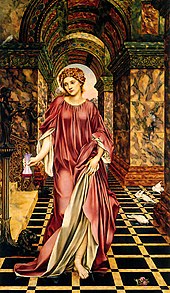

The Ger Eenens Collection The Netherlands includes a work by John Collier, Circe (signed and dated 1885), that was exhibited at the Chicago World Fair 1893.

There is a set of Pre-Raphaelite murals in the Old Library at the Oxford Union, depicting scenes from the Arthurian legends, painted between 1857 and 1859 by a team of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris, and Edward Burne-Jones.

Andrew Lloyd Webber is an avid collector of Pre-Raphaelite works, and a selection of 300 items from his collection were shown at an exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in 2003.

Kelmscott Manor, the country home of William Morris from 1871 until his death in 1896, is owned by the Society of Antiquaries of London and is open to the public.

"[39] Ken Russell's television film Dante's Inferno (1967) contains brief scenes on some of the leading Pre-Raphaelites but mainly concentrates on the life of Rossetti, played by Oliver Reed.