Science in classical antiquity

Science in classical antiquity encompasses inquiries into the workings of the world or universe aimed at both practical goals (e.g., establishing a reliable calendar or determining how to cure a variety of illnesses) as well as more abstract investigations belonging to natural philosophy.

[3] Around 450 BC we begin to see compilations of the seasonal appearances and disappearances of the stars in texts known as parapegmata, which were used to regulate the civil calendars of the Greek city-states on the basis of astronomical observations.

[5] This rivalry among these competing traditions contributed to an active public debate about the causes and proper treatment of disease, and about the general methodological approaches of their rivals.

[6] Nonetheless, observations of natural phenomena continued to be compiled in an effort to determine their causes, as for instance in the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus, who wrote extensively on animals and plants.

The legacy of Greek science in this era included substantial advances in factual knowledge due to empirical research (e.g., in zoology, botany, mineralogy, and astronomy), an awareness of the importance of certain scientific problems (e.g., the problem of change and its causes), and a recognition of the methodological significance of establishing criteria for truth (e.g., applying mathematics to natural phenomena), despite the lack of universal consensus in any of these areas.

[7] The earliest Greek philosophers, known as the pre-Socratics, were materialists who provided alternative answers to the same question found in the myths of their neighbors: "How did the ordered cosmos in which we live come to be?

Exactly what he meant is uncertain but it has been suggested that it was boundless in its quantity, so that creation would not fail; in its qualities, so that it would not be overpowered by its contrary; in time, as it has no beginning or end; and in space, as it encompasses all things.

He adduced common observations (the wine stealer) to demonstrate that air was a substance and a simple experiment (breathing on one's hand) to show that it could be altered by rarefaction and condensation.

[11] Finally, Empedocles of Acragas (490–430 BC), seems to have combined the views of his predecessors, asserting that there are four elements (Earth, Water, Air and Fire) which produce change by mixing and separating under the influence of two opposing "forces" that he called Love and Strife.

Although it is difficult to separate fact from legend, it appears that some Pythagoreans believed matter to be made up of ordered arrangements of points according to geometrical principles: triangles, squares, rectangles, or other figures.

[15] According to tradition, the physician Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 BC) is considered the "father of medicine" because he was the first to make use of prognosis and clinical observation, to categorize diseases, and to formulate the ideas behind humoral theory.

[17] Despite their wide variability in terms of style and method, the writings of the Hippocratic Corpus had a significant influence on the medical practice of Islamic and Western medicine for more than a thousand years.

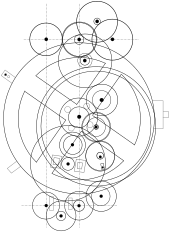

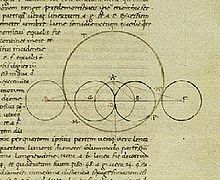

[18] The first institution of higher learning in Ancient Greece was founded by Plato (c. 427 – c. 347 BC), an Athenian who—perhaps under Pythagorean influence—appears to have identified the ordering principle of the universe as one based on number and geometry.

[21] For instance, Plato recommended that astronomy be studied in terms of abstract geometrical models rather than empirical observations,[22] and proposed that leaders be trained in mathematics in preparation for philosophy.

As one of the most prolific natural philosophers of Antiquity, Aristotle wrote and lecture on many topics of scientific interest, including biology, meteorology, psychology, logic, and physics.

The resulting migration of many Greek speaking populations across these territories provided the impetus for the foundation of several seats of learning, such as those in Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamum.

Unlike Plato's Academy and Aristotle's Lyceum, these institutions were officially supported by the Ptolemies, although the extent of patronage could be precarious depending on the policies of the current ruler.

[29] Hellenistic scholars often employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought in their scientific investigations, such as the application of mathematics to phenomena or the deliberate collection of empirical data.

[31] At the other end is the view of Italian physicist and mathematician Lucio Russo, who claims that the scientific method was actually born in the 3rd century BC, only to be largely forgotten during the Roman period and not revived again until the Renaissance.

[36] Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter, medical officials were allowed to cut open and examine cadavers for the purposes of learning how human bodies operated.

[44] Among the most recognizable is the work of Euclid (325–265 BC), who presumably authored a series of books known as the Elements, a canon of geometry and elementary number theory for many centuries.

Archimedes (287–212 BC), a Sicilian Greek, wrote about a dozen treatises where he communicated many remarkable results, such as the sum of an infinite geometric series in Quadrature of the Parabola, an approximation to the value π in Measurement of the Circle, and a nomenclature to express very large numbers in the Sand Reckoner.

[49][50] It has recently been claimed that a celestial globe based on Hipparchus's star catalog sits atop the broad shoulders of a large 2nd-century Roman statue known as the Farnese Atlas.

[citation needed] Even though science continued under Roman rule, Latin texts were mainly compilations drawing on earlier Greek work.

[53] Among his most famous inventions was a windwheel, constituting the earliest instance of wind harnessing on land, and a well-recognized description of a steam-powered device called an aeolipile, which was the first-recorded steam engine.

Galen was instructed in all major philosophical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism and Epicureanism) until his father, moved by a dream of Asclepius, decided he should study medicine.

[55] Galen compiled much of the knowledge obtained by his predecessors, and furthered the inquiry into the function of organs by performing dissections and vivisections on Barbary apes, oxen, pigs, and other animals.

[56] In 158 AD, Galen served as chief physician to the gladiators in his native Pergamon, and was able to study all kinds of wounds without performing any actual human dissection.

[59][60] Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD), living in or around Alexandria, carried out a scientific program centered on the writing of about a dozen books on astronomy, astrology, cartography, harmonics, and optics.

[64] Apart from astronomy, both the Harmonics and the Optics contain (in addition to mathematical analyses of sound and sight, respectively) instructions on how to construct and use experimental instruments to corroborate theory.