Protein structure prediction

Protein structure prediction is one of the most important goals pursued by computational biology and addresses Levinthal's paradox.

Glycine takes on a special position, as it has the smallest side chain, only one hydrogen atom, and therefore can increase the local flexibility in the protein structure.

The most common location of α-helices is at the surface of protein cores, where they provide an interface with the aqueous environment.

Other α-helices buried in the protein core or in cellular membranes have a higher and more regular distribution of hydrophobic amino acids, and are highly predictive of such structures.

Regions richer in alanine (A), glutamic acid (E), leucine (L), and methionine (M) and poorer in proline (P), glycine (G), tyrosine (Y), and serine (S) tend to form an α-helix.

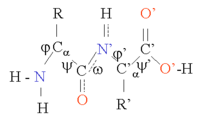

The Φ and Ψ angles of the amino acids in sheets vary considerably in one region of the Ramachandran plot.

The positions of introns in genomic DNA may correlate with the locations of loops in the encoded protein [citation needed].

Deltas also tend to have charged and polar amino acids and are frequently a component of active sites.

For proteins, a prediction consists of assigning regions of the amino acid sequence as likely alpha helices, beta strands (often termed extended conformations), or turns.

The accuracy of current protein secondary structure prediction methods is assessed in weekly benchmarks such as LiveBench and EVA.

[11] Significantly more accurate predictions that included beta sheets were introduced in the 1970s and relied on statistical assessments based on probability parameters derived from known solved structures.

[14] The theoretical upper limit of accuracy is around 90%,[14] partly due to idiosyncrasies in DSSP assignment near the ends of secondary structures, where local conformations vary under native conditions but may be forced to assume a single conformation in crystals due to packing constraints.

Dramatic conformational changes related to the protein's function or environment can also alter local secondary structure.

One of the first algorithms was Chou–Fasman method, which relies predominantly on probability parameters determined from relative frequencies of each amino acid's appearance in each type of secondary structure.

[15] The original Chou-Fasman parameters, determined from the small sample of structures solved in the mid-1970s, produce poor results compared to modern methods, though the parameterization has been updated since it was first published.

The original GOR method was roughly 65% accurate and is dramatically more successful in predicting alpha helices than beta sheets, which it frequently mispredicted as loops or disorganized regions.

[2] PSIPRED and JPRED are some of the most known programs based on neural networks for protein secondary structure prediction.

Next, support vector machines have proven particularly useful for predicting the locations of turns, which are difficult to identify with statistical methods.

[17][18] Extensions of machine learning techniques attempt to predict more fine-grained local properties of proteins, such as backbone dihedral angles in unassigned regions.

In contrast, the de novo protein structure prediction methods must explicitly resolve these problems.

There are many possible procedures that either attempt to mimic protein folding or apply some stochastic method to search possible solutions (i.e., global optimization of a suitable energy function).

To predict protein structure de novo for larger proteins will require better algorithms and larger computational resources like those afforded by either powerful supercomputers (such as Blue Gene or MDGRAPE-3) or distributed computing (such as Folding@home, the Human Proteome Folding Project and Rosetta@Home).

[43] The method, EVfold, uses no homology modeling, threading or 3D structure fragments and can be run on a standard personal computer even for proteins with hundreds of residues.

[48] These methods may also be split into two groups:[31] Accurate packing of the amino acid side chains represents a separate problem in protein structure prediction.

Rotamer libraries may contain information about the conformation, its frequency, and the standard deviations about mean dihedral angles, which can be used in sampling.

[54] The modern versions of these libraries as used in most software are presented as multidimensional distributions of probability or frequency, where the peaks correspond to the dihedral-angle conformations considered as individual rotamers in the lists.

[60] Some recent successful methods based on the CASP experiments include I-TASSER, HHpred and AlphaFold.

[61] The European Bioinformatics Institute together with DeepMind have constructed the AlphaFold – EBI database[62] for predicted protein structures.

AlphaFold2's accuracy has been evaluated against experimentally determined protein structures using metrics such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD).

For regions where AlphaFold2 assigns high confidence, the median RMSD is about 0.6 Å, comparable to the variability observed between different experimental structures.