Phage display

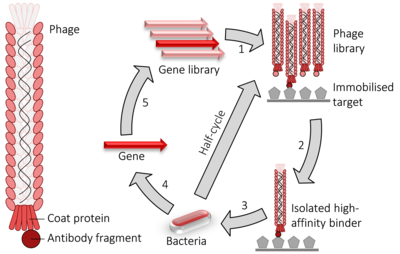

Phage display is a laboratory technique for the study of protein–protein, protein–peptide, and protein–DNA interactions that uses bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) to connect proteins with the genetic information that encodes them.

[5] In 1990, Jamie Scott and George Smith described creation of large random peptide libraries displayed on filamentous phage.

[6] Phage display technology was further developed and improved by groups at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology with Greg Winter and John McCafferty, The Scripps Research Institute with Richard Lerner and Carlos Barbas and the German Cancer Research Center with Frank Breitling and Stefan Dübel for display of proteins such as antibodies for therapeutic protein engineering.

Smith and Winter were awarded a half share of the 2018 Nobel Prize in chemistry for their contribution to developing phage display.

[10] Applications of phage display technology include determination of interaction partners of a protein (which would be used as the immobilised phage "bait" with a DNA library consisting of all coding sequences of a cell, tissue or organism) so that the function or the mechanism of the function of that protein may be determined.

[12][13][14] The technique is also used to determine tumour antigens (for use in diagnosis and therapeutic targeting)[15] and in searching for protein-DNA interactions[16] using specially-constructed DNA libraries with randomised segments.

Recently, phage display has also been used in the context of cancer treatments - such as the adoptive cell transfer approach.

[17] In these cases, phage display is used to create and select synthetic antibodies that target tumour surface proteins.

Initial work was done by laboratories at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (Greg Winter and John McCafferty), the Scripps Research Institute (Richard Lerner and Carlos F. Barbas) and the German Cancer Research Centre (Frank Breitling and Stefan Dübel).

One of the most successful was adalimumab, discovered by Cambridge Antibody Technology as D2E7 and developed and marketed by Abbott Laboratories.

[34] However, when using the BamHI site located at position 198 one must be careful of the unpaired Cysteine residue (C201) that could cause problems during phage display if one is using a non-truncated version of pIII.

Moreover, pIII allows for the insertion of larger protein sequences (>100 amino acids)[35] and is more tolerant to it than pVIII.

[42] However, phage display of cDNA is always limited by the inability of most prokaryotes in producing post-translational modifications present in eukaryotic cells or by the misfolding of multi-domain proteins.

While pVI has been useful for the analysis of cDNA libraries, pIII and pVIII remain the most utilized coat proteins for phage display.

[43] However, phage display of this protein was completed successfully after the addition of a periplasmic signal sequence (pelB or ompA) on the N-terminus.

[44] In a recent study, it has been shown that AviTag, FLAG and His could be displayed on pVII without the need of a signal sequence.

The paper even goes on to state that pVII and pIX display platforms may outperform pIII in the long run.

Users can use three dimensional structure of a protein and the peptides selected from phage display experiment to map conformational epitopes.