RNA-Seq

[7] Other examples of emerging RNA-Seq applications due to the advancement of bioinformatics algorithms are copy number alteration, microbial contamination, transposable elements, cell type (deconvolution) and the presence of neoantigens.

Issues with microarrays include cross-hybridization artifacts, poor quantification of lowly and highly expressed genes, and needing to know the sequence a priori.

[18] For Illumina short-read sequencing, a common technology for cDNA sequencing, adapters are ligated to the cDNA, DNA is attached to a flow cell, clusters are generated through cycles of bridge amplification and denaturing, and sequence-by-synthesis is performed in cycles of complementary strand synthesis and laser excitation of bases with reversible terminators.

[21] Another benefit of single-molecule RNA-Seq is that transcripts can be covered in full length, allowing for higher confidence isoform detection and quantification compared to short-read sequencing.

Recent uses of ONT direct RNA-Seq for differential expression in human cell populations have demonstrated that this technology can overcome many limitations of short and long cDNA sequencing.

[26][27] Current scRNA-Seq protocols involve the following steps: isolation of single cell and RNA, reverse transcription (RT), amplification, library generation and sequencing.

Single cells are either mechanically separated into microwells (e.g., BD Rhapsody, Takara ICELL8, Vycap Puncher Platform, or CellMicrosystems CellRaft) or encapsulated in droplets (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium, Illumina Bio-Rad ddSEQ, 1CellBio InDrop, Dolomite Bio Nadia).

[31] Challenges for scRNA-Seq include preserving the initial relative abundance of mRNA in a cell and identifying rare transcripts.

[32] The reverse transcription step is critical as the efficiency of the RT reaction determines how much of the cell's RNA population will be eventually analyzed by the sequencer.

The processivity of reverse transcriptases and the priming strategies used may affect full-length cDNA production and the generation of libraries biased toward the 3’ or 5' end of genes.

However, different PCR efficiency on particular sequences (for instance, GC content and snapback structure) may also be exponentially amplified, producing libraries with uneven coverage.

[40] These protocols differ in terms of strategies for reverse transcription, cDNA synthesis and amplification, and the possibility to accommodate sequence-specific barcodes (i.e. UMIs) or the ability to process pooled samples.

[41] In 2017, two approaches were introduced to simultaneously measure single-cell mRNA and protein expression through oligonucleotide-labeled antibodies known as REAP-seq,[42] and CITE-seq.

[49] scRNA-Seq has provided considerable insight into the development of embryos and organisms, including the worm Caenorhabditis elegans,[50] and the regenerative planarian Schmidtea mediterranea.

[77][78][79] Expression is quantified to study cellular changes in response to external stimuli, differences between healthy and diseased states, and other research questions.

Owing to the pitfalls of differential expression and RNA-Seq, important observations are replicated with (1) an orthogonal method in the same samples (like real-time PCR) or (2) another, sometimes pre-registered, experiment in a new cohort.

Common tools for gene set enrichment include web interfaces (e.g., ENRICHR, g:profiler, WEBGESTALT)[117] and software packages.

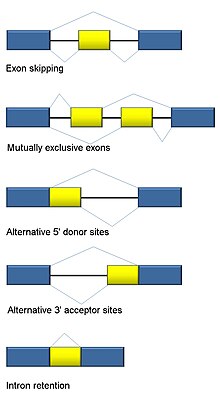

RNA splicing is integral to eukaryotes and contributes significantly to protein regulation and diversity, occurring in >90% of human genes.

Long-read sequencing captures the full transcript and thus minimizes many of issues in estimating isoform abundance, like ambiguous read mapping.

[130] The main advantage of RNA-Seq data in this kind of analysis over the microarray platforms is the capability to cover the entire transcriptome, therefore allowing the possibility to unravel more complete representations of the gene regulatory networks.

[136][137] Limitations of RNA variant identification include that it only reflects expressed regions (in humans, <5% of the genome), could be subject to biases introduced by data processing (e.g., de novo transcriptome assemblies underestimate heterozygosity[138]), and has lower quality when compared to direct DNA sequencing.

[139] The ability of RNA-Seq to analyze a sample's whole transcriptome in an unbiased fashion makes it an attractive tool to find these kinds of common events in cancer.

Nonetheless, the end result consists of multiple and potentially novel combinations of genes providing an ideal starting point for further validation.

[150] RNA-Seq has the potential to identify new disease biology, profile biomarkers for clinical indications, infer druggable pathways, and make genetic diagnoses.

The feasibility of this approach is in part dictated by costs in money and time; a related limitation is the required team of specialists (bioinformaticians, physicians/clinicians, basic researchers, technicians) to fully interpret the huge amount of data generated by this analysis.

[153] A lot of emphasis has been given to RNA-Seq data after the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) projects have used this approach to characterize dozens of cell lines[154] and thousands of primary tumor samples,[155] respectively.

TCGA, instead, aimed to collect and analyze thousands of patient's samples from 30 different tumor types to understand the underlying mechanisms of malignant transformation and progression.