Reliability engineering

[1] Reliability is closely related to availability, which is typically described as the ability of a component or system to function at a specified moment or interval of time.

[2][3] "Nearly all teaching and literature on the subject emphasize these aspects and ignore the reality that the ranges of uncertainty involved largely invalidate quantitative methods for prediction and measurement.

The nature of predictions evolved during the decade, and it became apparent that die complexity wasn't the only factor that determined failure rates for integrated circuits (ICs).

Wider use of stand-alone microcomputers was common, and the PC market helped keep IC densities following Moore's law and doubling about every 18 months.

New technologies such as micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), handheld GPS, and hand-held devices that combine cell phones and computers all represent challenges to maintaining reliability.

Reliability is the probability of a product performing its intended function under specified operating conditions in a manner that meets or exceeds customer expectations.

Consistent with the creation of safety cases, for example per ARP4761, the goal of reliability assessments is to provide a robust set of qualitative and quantitative evidence that the use of a component or system will not be associated with unacceptable risk.

A more complete definition of failure also can mean injury, dismemberment, and death of people within the system (witness mine accidents, industrial accidents, space shuttle failures) and the same to innocent bystanders (witness the citizenry of cities like Bhopal, Love Canal, Chernobyl, or Sendai, and other victims of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami)—in this case, reliability engineering becomes system safety.

It is supported by leadership, built on the skills that one develops within a team, integrated into business processes, and executed by following proven standard work practices.

When reliability is not under control, more complicated issues may arise, like manpower (maintainers/customer service capability) shortages, spare part availability, logistic delays, lack of repair facilities, extensive retrofit and complex configuration management costs, and others.

But, as GM and Toyota have belatedly discovered, TCO also includes the downstream liability costs when reliability calculations have not sufficiently or accurately addressed customers' bodily risks.

In the case of reliability, the levels of unreliability (failure rates) may change with factors of decades (multiples of 10) as a result of very minor deviations in design, process, or anything else.

Understanding of this difference compared to only purely quantitative (logistic) requirement specification (e.g., Failure Rate / MTBF target) is paramount in the development of successful (complex) systems.

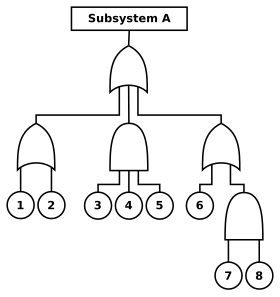

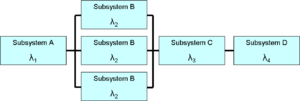

Reliability and availability models use block diagrams and Fault Tree Analysis to provide a graphical means of evaluating the relationships between different parts of the system.

The reason why this is the ultimate design choice is related to the fact that high-confidence reliability evidence for new parts or systems is often not available, or is extremely expensive to obtain.

In conjunction with redundancy, the use of dissimilar designs or manufacturing processes (e.g. via different suppliers of similar parts) for single independent channels, can provide less sensitivity to quality issues (e.g. early childhood failures at a single supplier), allowing very-high levels of reliability to be achieved at all moments of the development cycle (from early life to long-term).

Redundancy can also be applied in systems engineering by double checking requirements, data, designs, calculations, software, and tests to overcome systematic failures.

Another effective way to deal with reliability issues is to perform analysis that predicts degradation, enabling the prevention of unscheduled downtime events / failures.

Many of the tasks, techniques, and analyses used in Reliability Engineering are specific to particular industries and applications, but can commonly include: Results from these methods are presented during reviews of part or system design, and logistics.

Reliability engineers, whether using quantitative or qualitative methods to describe a failure or hazard, rely on language to pinpoint the risks and enable issues to be solved.

To do this, first the reliability hazards relating to the part/system need to be classified and ordered (based on some form of qualitative and quantitative logic if possible) to allow for more efficient assessment and eventual improvement.

For part level predictions, two separate fields of investigation are common: Reliability is defined as the probability that a device will perform its intended function during a specified period of time under stated conditions.

[26] Most product on the market requires reliability testing, such as automotive, integrated circuit, heavy machinery used to mine nature resources, Aircraft auto software.

It primarily focuses on system safety hazards that could lead to severe accidents including: loss of life; destruction of equipment; or environmental damage.

Another difference is the level of impact of failures on society, leading to a tendency for strict control by governments or regulatory bodies (e.g. nuclear, aerospace, defense, rail and oil industries).

In cases where manufacturing variances can be effectively reduced, six sigma tools have been shown to be useful to find optimal process solutions which can increase quality and reliability.

Solutions are found in different ways, such as by simplifying a system to allow more of the mechanisms of failure involved to be understood; performing detailed calculations of material stress levels allowing suitable safety factors to be determined; finding possible abnormal system load conditions and using this to increase robustness of a design to manufacturing variance related failure mechanisms.

The reliability program also includes a systematic root cause analysis that identifies the causal relationships involved in the failure such that effective corrective actions may be implemented.

Organizations today are adopting this method and utilizing commercial systems (such as Web-based FRACAS applications) that enable them to create a failure/incident data repository from which statistics can be derived to view accurate and genuine reliability, safety, and quality metrics.

Some of the common outputs from a FRACAS system include Field MTBF, MTTR, spares consumption, reliability growth, failure/incidents distribution by type, location, part no., serial no., and symptom.