Hoodoo (spirituality)

"[37] The Code Noir and other slave laws resulted in enslaved and free African Americans conducting their spiritual practices in secluded areas such as woods (hush harbors), churches, and other places.

The leader of the revolt was a free African conjurer named Peter the Doctor, who made a magical powder for the enslaved people to be rubbed on the body and clothes for their protection and empowerment.

Historians suggest the powder made by Peter the Doctor probably included some cemetery dirt to conjure the ancestors to provide spiritual militaristic support from ancestral spirits as help during the slave revolt.

In addition, altars with white candles and offerings are placed in areas where police murdered an African American, and libation ceremonies and other spiritual practices are performed to heal the soul that died from racial violence.

"In their physical manifestations, minkisi (nkisi) are sacred objects that embody spiritual beings and generally take the form of a container such as a gourd, pot, bag, or snail shell.

Archeologists found objects believed by the enslaved African American population in Virginia and Maryland to have spiritual power, such as coins, crystals, roots, fingernail clippings, crab claws, beads, iron, bones, and other items assembled inside a bundle to conjure a specific result for either protection or healing.

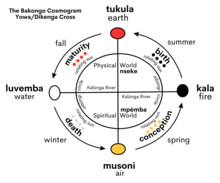

[135] At Locust Grove plantation in Jefferson County, Kentucky, archeologists and historians found amulets made by enslaved African Americans that had the Kongo cosmogram engraved onto coins and beads.

[140] Former academic historian Albert J. Raboteau in his book, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South, traced the origins of Hoodoo (conjure, rootwork) practices in the United States to West and Central Africa.

[159][160] In addition, at the Kingsmill Plantation in Williamsburg, Virginia, enslaved blacksmiths created spoons that historians suggest have West African symbols carved onto them that have a spiritual cosmological meaning.

[165][166] The practice of carving snakes onto "conjure sticks" to remove curses and evil spirits and bring healing was found in African American communities in the Sea Islands among the Gullah Geechee people.

These areas in Africa were suitable for rice cultivation because of their moist semitropical climate; the European slave traders selected people belonging to ethnic groups from these regions to be enslaved and transported to the Sea Islands.

[177] During the transatlantic slave trade a variety of African plants were brought from Africa to the United States for cultivation, including okra, sorghum, yam, benneseed (sesame), watermelon, black-eyed peas, and kola nuts.

The remedy most commonly used in Black communities in northeast Missouri to ward off a cold was carrying a small bag of Ferula assafoetida; the folk word is asfidity, a plant from the fennel family.

[221] The concepts of Kongo Christianity[222] among the Bakongo people was brought to the United States during the transatlantic slave trade and developed into Afro-Christianity among African Americans that is seen in Hoodoo and some Black churches.

These traits included naturopathic medicine, ancestor reverence, counter-clockwise sacred circle dancing, blood sacrifice, divination, supernatural source of malady, water immersion, and spirit possession.

Examples of enslaved and free Black people using the Bible as a tool for liberation were Denmark Vesey's slave revolt in South Carolina in 1822 and Nat Turner's Rebellion in Virginia in 1831.

After the American Civil War, before High John the Conqueror returned to Africa, he told the newly freed slaves that if they ever needed his spirit for freedom, it would reside in a root they could use.

[263] The earliest known reference to Simbi spirits in the United States was recorded in the nineteenth century by Edmund Ruffin, a wealthy enslaver from Virginia who traveled to South Carolina "to keep the slave economic system viable through agricultural reform".

To obtain the powers of the Bisimbi, Bakongo people in Central Africa and African Americans in the Georgia and South Carolina Lowcountry collect rocks and seashells and create minkisi bundles.

To calm the spirits of ancestors, African Americans leave the last objects they used in life on top of their graves, believing them to contain the last essence of the person before they died, as a way of acknowledging them.

The items are placed inside conjure bags or jars and mixed with roots, herbs, and animal parts, sometimes ground into a powder or with graveyard dirt from a murdered victim's grave.

A Spiritual church in New Orleans called the Temple of the Innocent Blood was led by an African American woman, Mother Catherine Seals, who performed Hoodoo to heal her clients.

Hurston noted that Mother Seals incorporated other African Diaspora practices into her Spiritual church and observed her reverence for a Haitian Vodou snake loa spirit, Damballa.

By the end of the book, Milkman learns he comes from a family of African medicine people, gains his ancestral powers, and his soul flies back to Africa after he dies.

In her "Louisiana Hoodoo Blues", Gertrude Ma Rainey sang about a Hoodoo work to keep a man faithful: "Take some of you hair, boil it in a pot, Take some of your clothes, tie them in a knot, Put them in a snuff can, bury them under the step...."[398] Bessie Smith's song "Red Mountain Blues" tells of a fortune teller who recommends that a woman get some snakeroot and a High John the Conqueror root, chew them, place them in her boot and pocket to make her man love her.

[399] The song "Got My Mojo Working", written by Preston "Red" Foster in 1956 and popularized by Muddy Waters throughout his career, addresses a woman who can resist the power of the singer's Hoodoo amulets.

Hoodoo practitioner Aunt Caroline Dye was born enslaved in Spartanburg, South Carolina and sold to Newport, Arkansas as a child, where she became known for soothsaying and divination with playing cards.

[402][403][404] However, the devil figure in Johnson's song, a black man with a cane who haunts crossroads, closely resembles Papa Legba, a spirit associated with Louisiana Voodoo and Haitian Vodou.

[409][410][411] For example, High John the Conqueror in African American folk stories is a Black man from Africa enslaved in the United States whose spirit resides in a root conjured in Hoodoo.

White merchants profited from African American folk magic and placed stereotypical images of Indians onto hoodoo product labels to sell merchandise that appeared mystical, exotic, and powerful.