Sargon II

He forgave defeated enemies on several occasions and maintained good relations with foreign kings and with the ruling classes of the lands he conquered.

[9] Sargon grew up during the reigns of Ashur-dan III (r. 773–755) and Ashur-nirari V (r. 755–745), when rebellion and plague affected the Neo-Assyrian Empire; the prestige and power of Assyria dramatically declined.

[16][17] Sargon mentioned his origin in just two known inscriptions, where he referred to himself as Tiglath-Pileser's son, and in the Borowski Stele, probably from Hama in Syria, which referenced his "royal fathers".

Another alternative is that Šarru-kīn is a phonetic reproduction of the contracted pronunciation of Šarru-ukīn to Šarrukīn, which means that it should be interpreted as "the king has obtained/established order", possibly referencing disorder either under his predecessor or caused by Sargon's usurpation.

In early 721, Marduk-apla-iddina II, a Chaldean warlord of the Bit-Yakin tribe, captured Babylon, restored Babylonian independence after eight years of Assyrian rule and allied with the eastern realm of Elam.

[41] Though likely emotionally damaging for the resettled populace, the Assyrians valued deportees for their labor and generally treated them well, transporting them in safety and comfort together with their families and belongings.

[45] The revolt threatened to undo the administrative system established in Syria by Sargon's predecessors[38] and the insurgents went on a killing spree, murdering all local Assyrians they could find.

After capturing some other cities on his way, probably including Ekron and Gibbethon, the Assyrians defeated Hanunu, whose army had been bolstered by allies from Egypt, at Rafah.

[49] Though no longer as powerful as it had been in the past, when it at times rivalled Assyria in strength and influence,[50] Urartu still remained an alternative suzerain for many smaller states in the north.

[52] Sargon worried about a possible alliance between Phrygia and Urartu and Midas' use of proxy warfare by encouraging Assyrian vassal states to rebel.

[55] Sargon established a new trading post near the border of Egypt in 716, staffed it with people deported from various conquered lands and placed it under the local Arab ruler Laban, an Assyrian vassal.

Passing through Mannaea, Sargon attacked Media, probably to establish control there and neutralize the region as a potential threat before confronting either Urartu or Elam.

Rejecting the shortest route through the Kel-i-šin pass, Sargon marched his army through the valleys of the Great and Little Zab for three days before halting near Mount Kullar (the location of which remains unidentified).

[65] On their way home, the Assyrians destroyed the Gerdesorah and captured and plundered Musasir[64] after the local governor, king Urzana, refused to welcome Sargon.

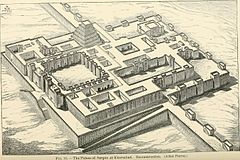

[38] The numerous surviving sources on the construction of the city include inscriptions carved on the walls of its buildings, reliefs depicting the process and over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work.

Sargon took an active personal interest in the progress and frequently intervened in nearly all aspects of the work, from commenting on architectural details to overseeing material transportation and the recruitment of labor.

In 713 Sargon campaigned against Tabal in southern Anatolia again, trying to secure the kingdom's natural resources (mainly silver and wood, required for the construction of Dur-Sharrukin) and to prevent Urartu from establishing control and contacting Phrygia.

[80] Sargon invaded Babylonia by marching alongside the eastern bank of the river Tigris until he reached the city of Dur-Athara, which had been fortified by Marduk-apla-iddina (moving also the entire Gambulu tribe, an Aramean people, into it), but was quickly defeated and renamed Dur-Nabu.

As the siege dragged on, negotiations were started and in 709 it was agreed that the city would surrender and tear down its exterior walls in exchange for Sargon sparing Marduk-apla-iddina's life.

Sargon participated in the annual Babylonian Akitu (New Years) festival and received homage and gifts from rulers of lands as far away from the heartland of his empire as Bahrain and Cyprus.

[85] Sargon engaged himself in various domestic affairs in Babylonia, digging a new canal from Borsippa to Babylon and defeating a people called the Hamaranaeans that had been plundering caravans near Sippar.

Sargon invited "princes of (all) countries, the governors of my land, scribes and superintendents, nobles, officials and elders of Assyria" to a great feast.

He was named crown prince early in Sargon's reign and assisted his father in running the empire;[1] he helped collect and summarize intelligence reports from the Assyrian spy network.

[113] Sargon's epithets present him as if he were an invincible warlord, for example, "mighty hero, clothed with terror, who sends forth his weapon to bring low the foe, brave warrior, since the day of whose (accession) to rulership, there has been no prince equal to him, who has been without conqueror or rival".

Sargon is unlikely to have fought on the frontlines in all campaigns since this would greatly have jeopardized the empire, but it is clear that he was more interested in participating in war than his predecessors and successors and he did eventually die in battle.

[133] Atrocities enacted by Assyrian kings were in most known cases directed only towards soldiers and elites; as of 2016 none of the known inscriptions or reliefs of Sargon mention or show harm being done to civilians.

[30][122] Soon after the news of Sargon's death reached the Assyrian heartland, the influential advisor and scribe Nabu-zuqup-kena copied Tablet XII of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

[85][95] One of his first building projects was restoring a temple dedicated to Nergal, god of the underworld, perhaps intended to pacify a deity possibly involved with Sargon's fate.

[147] Many Assyriological commentators were puzzled by the name's appearance in the Bible and believed that Sargon was merely an alias for one of the better-known kings, typically Shalmaneser, Sennacherib or Esarhaddon.

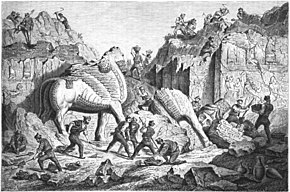

[151] Though much of what was excavated at Dur-Sharrukin was left in situ, reliefs and other artifacts have been exhibited across the world, including the Louvre, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Iraq Museum.