Toledo School of Translators

The first was led by Archbishop Raymond of Toledo in the 12th century, who promoted the translation of philosophical and religious works, mainly from classical Arabic into medieval Latin.

Some of the Arabic literature was also translated into Latin, Hebrew, and Ladino, such as that of Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, Muslim sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun, Carthage citizen Constantine the African, or the Persian Al-Khwarizmi.

[3] Al-Andalus's multi-cultural richness beginning in the era of Umayyad dynasty rule in that land (711-1031) was one of the main reasons why European scholars were traveling to study there as early as the end of the 10th century.

Another reason for Al-Andalus's importance at the time is that some Christian leaders in certain other parts of Europe considered a few scientific and theological subjects studied by the ancients, and further advanced by the Arabic-speaking scientists and philosophers, to be heretical.

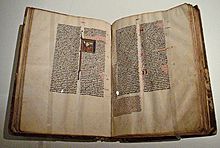

[7] As a result, the library of the cathedral, which had been refitted under Raymond's orders, became a translations center of a scale and importance not matched in the history of western culture.

His translated books include the following: He edited for Latin readers the "Toledan Tables", the most accurate compilation of astronomical/astrological data (ephemeris) ever seen in Europe at the time, which were partly based on the work of al-Zarqali and the works of Jabir ibn Aflah, the Banu Musa brothers, Abu Kamil, Abu al-Qasim, and Ibn al-Haytham (including the Book of Optics).

John of Seville translated Secretum Secretorum, a 10th-century Arabic encyclopedic treatise on a wide range of topics, including statecraft, ethics, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, magic and medicine, which was very influential in Europe during the High Middle Ages.

He translated into Latin the Liber de compositione astrolabii, a major work of Islamic science on the astrolabe, by Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti,[13] which he dedicated to his colleague John of Seville.

Unlike his colleagues, he focused exclusively on philosophy, translating Greek and Arabic works and the commentaries of earlier Muslim philosophers of the peninsula.

[15] He translated Aristotle's works on homocentric spheres, De verificatione motuum coelestium, later used by Roger Bacon, and Historia animalium, 19 books, dated Oct 21, 1220.

Under King Alfonso X of Castile (known as the Wise), Toledo rose even higher in importance as a translation center, as well as for the writing of original scholarly works.

The King also commissioned the translation into Castilian of several "oriental" fables and tales which, although written in Arabic, were originally in Sanskrit, such as the Kalila wa-Dimna (Panchatantra) and the Sendebar.

Previously, a native speaker would verbally communicate the contents of the books to a scholar, who would dictate its Latin equivalent to a scribe, who wrote down the translated text.

[24] Alfonso's nephew Juan Manuel wrote that the King was so impressed with the intellectual level of the Jewish scholars that he commissioned the translation of the Talmud, the law of the Jews, as well as the Kabbalah.

The first known translation of this period, the Lapidario, a book about the medical properties of various rocks and gems, was done by Yehuda ben Moshe Cohen assisted by Garci Pérez, when Alfonso was still infante.

[27] Yehuda ben Moshe also collaborated in the translation of the Libro de las cruces, Libros del saber de Astronomía, and the famous Alfonsine tables, compiled by Isaac ibn Sid, that provided data for computing the position of the Sun, Moon and planets relative to the fixed stars, based on observations of astronomers that Alfonso had gathered in Toledo.

Isaac ibn Sid was another renowned Jewish translator favored by the King; he was highly learned on astronomy, astrology, architecture and mathematics.

King Alfonso wrote a preface to Isaac ibn Sid's translation, Lamina Universal, explaining that the original Arabic work was done in Toledo and from it Arzarquiel made his açafea.

Abraham of Toledo, physician to both Alfonso and his son Sancho, translated several books from Arabic into Spanish (Castilian), such as Al-Heitham's treatise on the construction of the universe, and al-Zarqālī's Astrolabe.

After Alfonso's death, Sancho IV of Castile, his self-appointed successor, dismantled most of the team of translators, and soon most of its members transferred their efforts to other activities under new patronages, many of them leaving the city of Toledo.

Although the works of Aristotle and Arab philosophers were banned at some European learning centers, such as the University of Paris in the early 1200s,[30] the Toledo's translations were accepted, due to their physical and cosmological nature.

Albertus Magnus based his systematization of Aristotelian philosophy, and much of his writings on astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, chemistry, zoology, physiology, and phrenology upon those translations made in Toledo.

Roger Bacon relied on many of the Arabic translations to make important contributions in the fields of optics, astronomy, the natural sciences, chemistry and mathematics.

[33] Nicolaus Copernicus, the first scientist to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology, which placed the sun instead of the earth at the center of the universe, studied the translation of Ptolemy's astronomical Almagest.

[36] Another side effect of this linguistic enterprise was the promotion of a revised version of the Castilian language which, although it incorporated a large amount of scientific and technical vocabulary, had streamlined its syntax in order to be understood by people from all walks of life and to reach the masses, while being made suitable for higher expressions of thought.