Silk Road

Aside from generating substantial wealth for emerging mercantile classes, the proliferation of goods such as paper and gunpowder greatly affected the trajectory of political history in several theatres in Eurasia and beyond.

[17] Going as far as to call the whole thing a "myth" of modern academia, Ball argues that there was no coherent overland trade system and no free movement of goods from East Asia to the West until the period of the Mongol Empire.

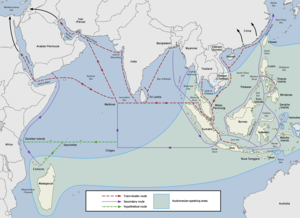

[18] William Dalrymple points out that in pre-modern times, maritime travel cost only a fifth of overland transport,[19] and argues for the pre-13th century primacy of an India-dominated "Golden Road" extending from Rome to Japan.

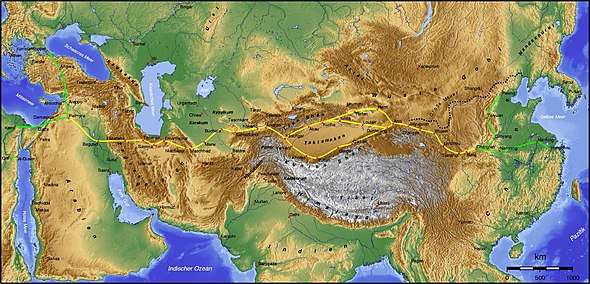

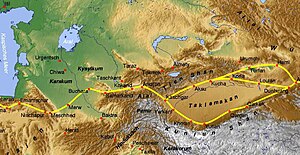

As it extended westwards from the ancient commercial centres of China, the overland, intercontinental Silk Road divided into northern and southern routes bypassing the Taklamakan Desert and Lop Nur.

Another branch road travelled from Herat through Susa to Charax Spasinu at the head of the Persian Gulf and across to Petra and on to Alexandria and other eastern Mediterranean ports from where ships carried the cargoes to Rome.

His comments are interesting as Roman beads and other materials are being found at Wari-Bateshwar ruins, the ancient city with roots from much earlier, before the Bronze Age, presently being slowly excavated beside the Old Brahmaputra in Bangladesh.

Ptolemy's map of the Ganges Delta, a remarkably accurate effort, showed that his informants knew all about the course of the Brahmaputra River, crossing through the Himalayas then bending westward to its source in Tibet.

The emerging evidence of the ancient cities of Bangladesh, in particular Wari-Bateshwar ruins, Mahasthangarh, Bhitagarh, Bikrampur, Egarasindhur, and Sonargaon, are believed to be the international trade centers in this route.

[30] The Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia who sailed large long-distance ocean-going sewn-plank and lashed-lug trade ships.

[29][43] The main route of the western regions of the Maritime Silk Road directly crosses the Indian Ocean from the northern tip of Sumatra (or through the Sunda Strait) to Sri Lanka, southern India and Bangladesh, and the Maldives.

[10] Archeological sites, such as the Berel burial ground in Kazakhstan, confirmed that the nomadic Arimaspians were not only breeding horses for trade but also produced great craftsmen able to propagate exquisite art pieces along the Silk Road.

[49] The expansion of Scythian cultures, stretching from the Hungarian plain and the Carpathian Mountains to the Chinese Gansu Corridor, and linking the Middle East with Northern India and the Punjab, undoubtedly played an important role in the development of the Silk Road.

These nomadic peoples were dependent upon neighbouring settled populations for a number of important technologies, and in addition to raiding vulnerable settlements for these commodities, they also encouraged long-distance merchants as a source of income through the enforced payment of tariffs.

This extension came around 130 BCE, with the embassies of the Han dynasty to Central Asia following the reports of the ambassador Zhang Qian[53] (who was originally sent to obtain an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu).

Zhang Qian visited directly the kingdom of Dayuan in Ferghana, the territories of the Yuezhi in Transoxiana, the Bactrian country of Daxia with its remnants of Greco-Bactrian rule, and Kangju.

[54] Zhang Qian's report suggested the economic reason for Chinese expansion and wall-building westward, and trail-blazed the Silk Road, making it one of the most famous trade routes in history and in the world.

[56] Some say that the Chinese Emperor Wu became interested in developing commercial relationships with the sophisticated urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria, and the Parthian Empire: "The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: Ferghana (Dayuan "Great Ionians") and the possessions of Bactria (Ta-Hsia) and Parthian Empire (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China" (Hou Hanshu, Later Han History).

Thus more embassies were dispatched to Anxi [Parthia], Yancai [who later joined the Alans ], Lijian [Syria under the Greek Seleucids], Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia), and Tianzhu [northwestern India] ... As a rule, rather more than ten such missions went forward in the course of a year, and at the least five or six.

[62] The Chinese campaigned in Central Asia on several occasions, and direct encounters between Han troops and Roman legionaries (probably captured or recruited as mercenaries by the Xiong Nu) are recorded, particularly in the 36 BCE battle of Sogdiana (Joseph Needham, Sidney Shapiro).

Han general Ban Chao led an army of 70,000 mounted infantry and light cavalry troops in the 1st century CE to secure the trade routes, reaching far west to the Tarim Basin.

[71][72] Soon after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, regular communications and trade between China, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe blossomed on an unprecedented scale.

[96][97][68] Although the Silk Road was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141–87 BCE), it was reopened by the Tang Empire in 639 when Hou Junji conquered the Western Regions, and remained open for almost four decades.

It was closed after the Tibetans captured it in 678, but in 699, during Empress Wu's period, the Silk Road reopened when the Tang reconquered the Four Garrisons of Anxi originally installed in 640,[98] once again connecting China directly to the West for land-based trade.

The Tang dynasty established a second Pax Sinica, and the Silk Road reached its golden age, whereby Persian and Sogdian merchants benefited from the commerce between East and West.

[106] Under its strong integrating dynamics on the one hand and the impacts of change it transmitted on the other, tribal societies previously living in isolation along the Silk Road, and pastoralists who were of barbarian cultural development, were drawn to the riches and opportunities of the civilisations connected by the routes, taking on the trades of marauders or mercenaries.

The Turko-Mongol ruler Timur forcefully moved artisans and intellectuals from across Asia to Samarkand, making it one of the most important trade centers and cultural entrepôts of the Islamic world.

The Mongol rulers wanted to establish their capital on the Central Asian steppe, so to accomplish this goal, after every conquest they enlisted local people (traders, scholars, artisans) to help them construct and manage their empire.

Eventually, the Mongols in the Ilkhanate, after they had destroyed the Abbasid and Ayyubid dynasties, converted to Islam and signed the 1323 Treaty of Aleppo with the surviving Muslim power, the Egyptian Mamluks.

[125] Richard Foltz, Xinru Liu, and others have described how trading activities along the Silk Road over many centuries facilitated the transmission not just of goods but also ideas and culture, notably in the area of religions.

[141] Knowledge among people on the silk roads also increased when Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya dynasty (268–239 BCE) converted to Buddhism and raised the religion to official status in his northern Indian empire.