Molecular scale electronics

Because single molecules constitute the smallest stable structures imaginable[citation needed], this miniaturization is the ultimate goal for shrinking electrical circuits.

Ever since their invention in 1958, the performance and complexity of integrated circuits has undergone exponential growth, a trend named Moore’s law, as feature sizes of the embedded components have shrunk accordingly.

[citation needed] However, the unceasing demand for more computing power, along with the inherent limits of lithographic methods as of 2016[update], make the transition seem unavoidable.

Currently, the focus is on discovering molecules with interesting properties and on finding ways to obtain reliable and reproducible contacts between the molecular components and the bulk material of the electrodes.

The significant amount of energy due to charging must be accounted for when making calculations about the electronic properties of the setup, and is highly sensitive to distances to conducting surfaces nearby.

In the low bias voltage regime, the nonequilibrium nature of the molecular junction can be ignored, and the current-voltage traits of the device can be calculated using the equilibrium electronic structure of the system.

In inelastic tunneling, an elegant formalism based on the non-equilibrium Green's functions of Leo Kadanoff and Gordon Baym, and independently by Leonid Keldysh was advanced by Ned Wingreen and Yigal Meir.

Further, connecting single molecules reliably to a larger scale circuit has proven a great challenge, and constitutes a significant hindrance to commercialization.

Common for molecules used in molecular electronics is that the structures contain many alternating double and single bonds (see also Conjugated system).

Semiconducting carbon nanotubes have also been demonstrated to work as channel material but although molecular, these molecules are sufficiently large to behave almost as bulk semiconductors.

Both groups expect (the designs were experimentally unverified as of June 2005[update]) their respective devices to function at room temperature, and to be controlled by a single electron.

Because the current photolithographic technology is unable to produce electrode gaps small enough to contact both ends of the molecules tested (on the order of nanometers), alternative strategies are applied.

Further, the contact resistance is highly dependent on the precise atomic geometry around the site of anchoring and thereby inherently compromises the reproducibility of the connection.

However, by the close of the twentieth century, chemists were exploring methods to fabricate extremely small graphitic objects that could be considered single molecules.

After studying the interstellar conditions under which carbon is known to form clusters, Richard Smalley's group (Rice University, Texas) set up an experiment in which graphite was vaporized via laser irradiation.

Harry Kroto, an English chemist who assisted in the experiment, suggested a possible geometry for these clusters – atoms covalently bound with the exact symmetry of a soccer ball.

In their treatment of so-called donor-acceptor complexes in the 1940s, Robert Mulliken and Albert Szent-Györgyi advanced the concept of charge transfer in molecules.

The direct measurement of the electronic traits of individual molecules awaited the development of methods for making molecular-scale electrical contacts.

[12] Having both huge commercial and fundamental interest, much effort was put into proving its feasibility, and 16 years later in 1990, the first demonstration of an intrinsic molecular rectifier was realized by Ashwell and coworkers for a thin film of molecules.

This was the conclusion of 10 years of research started at IBM TJ Watson, using the scanning tunnelling microscope tip apex to switch a single molecule as already explored by A. Aviram, C. Joachim and M. Pomerantz at the end of the 1980s (see their seminal Chem.

The trick was to use a UHV Scanning Tunneling microscope to allow the tip apex to gently touch the top of a single C60 molecule adsorbed on an Au(110) surface.

This first experiment was followed by the reported result using a mechanical break junction method to connect two gold electrodes to a sulfur-terminated molecular wire by Mark Reed and James Tour in 1997.

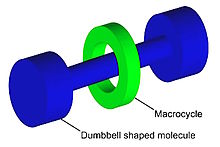

A collaboration of researchers at Hewlett-Packard (HP) and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), led by James Heath, Fraser Stoddart, R. Stanley Williams, and Philip Kuekes, has developed molecular electronics based on rotaxanes and catenanes.

Some specific reports of a field-effect transistor based on molecular self-assembled monolayers were shown to be fraudulent in 2002 as part of the Schön scandal.

For example, Bumm, et al. used STM to analyze a single molecular switch in a self-assembled monolayer to determine how conductive such a molecule can be.

[20] Another problem faced by this field is the difficulty of performing direct characterization since imaging at the molecular scale is often difficult in many experimental devices.