Soap

[2] Humans have used soap for millennia; evidence exists for the production of soap-like materials in ancient Babylon around 2800 BC.

In hand washing, as a surfactant, when lathered with a little water, soap kills microorganisms by disorganizing their membrane lipid bilayer and denaturing their proteins.

In ancient times, lubricating greases were made by the addition of lime to olive oil, which would produce calcium soaps.

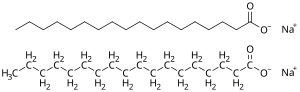

An alkaline solution (often lye or sodium hydroxide) induces saponification whereby the triglyceride fats first hydrolyze into salts of fatty acids.

[10][11] Handmade soap can differ from industrially made soap in that an excess of fat or coconut oil beyond that needed to consume the alkali is used (in a cold-pour process, this excess fat is called "superfatting"), and the glycerol left in acts as a moisturizing agent.

Proto-soaps, which mixed fat and alkali and were used for cleansing, are mentioned in Sumerian, Babylonian and Egyptian texts.

[15][16] The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BC in ancient Babylon.

This was produced by heating a mixture of oil and wood ash, the earliest recorded chemical reaction, and used for washing woolen clothing.

[18] The Ebers papyrus (Egypt, 1550 BC) indicates the ancient Egyptians used a soap-like product as a medicine and created this by combining animal fats or vegetable oils with a soda ash substance called trona.

[15][20] Knowledge of how to produce true soap emerged at some point between early mentions of proto-soaps and the first century AD.

[15] Experiments by Sally Pointer show that the repeated laundering of materials used in perfume-making lead to noticeable amounts of soap forming.

[15] Pliny the Elder, whose writings chronicle life in the first century AD, describes soap as "an invention of the Gauls".

It first appears in Pliny the Elder's account,[24] Historia Naturalis, which discusses the manufacture of soap from tallow and ashes.

There he mentions its use in the treatment of scrofulous sores, as well as among the Gauls as a dye to redden hair which the men in Germania were more likely to use than women.

[30] The 2nd-century AD physician Galen describes soap-making using lye and prescribes washing to carry away impurities from the body and clothes.

[31] In the Southern Levant, the ashes from barilla plants, such as species of Salsola, saltwort (Seidlitzia rosmarinus) and Anabasis, were used to make potash.

[32][33] Traditionally, olive oil was used instead of animal lard throughout the Levant, which was boiled in a copper cauldron for several days.

[34] As the boiling progresses, alkali ashes and smaller quantities of quicklime are added and constantly stirred.

Aromatic herbs were often added to the rendered soap to impart their fragrance, such as yarrow leaves, lavender, germander, etc.

[35] Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was produced in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, when soap-making became an established industry.

By the 13th century, the manufacture of soap in the Middle East had become a major cottage industry, with sources in Nablus, Fes, Damascus, and Aleppo.

[37][43] By the 15th century, the manufacture of soap in Christendom often took place on an industrial scale, with sources in Antwerp, Castile, Marseille, Naples and Venice.

[48][49][50] Industrially manufactured bar soaps became available in the late 18th century, as advertising campaigns in Europe and America promoted popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health.

[51] In modern times, the use of soap has become commonplace in industrialized nations due to a better understanding of the role of hygiene in reducing the population size of pathogenic microorganisms.

In 1780, James Keir established a chemical works at Tipton, for the manufacture of alkali from the sulfates of potash and soda, to which he afterwards added a soap manufactory.

[54] In 1882, Barratt recruited English actress and socialite Lillie Langtry to become the poster-girl for Pears soap, making her the first celebrity to endorse a commercial product.

American manufacturer Benjamin T. Babbitt introduced marketing innovations that included the sale of bar soap and distribution of product samples.

Such products as Pine-Sol and Tide appeared on the market, making the process of cleaning things other than skin, such as clothing, floors, and bathrooms, much easier.