Textual criticism

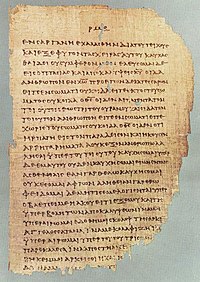

Historically, scribes who were paid to copy documents may have been literate, but many were simply copyists, mimicking the shapes of letters without necessarily understanding what they meant.

Textual criticism was an important aspect of the work of many Renaissance humanists, such as Desiderius Erasmus, who edited the Greek New Testament, creating what developed as the Textus Receptus.

In Italy, scholars such as Petrarch and Poggio Bracciolini collected and edited many Latin manuscripts, while a new spirit of critical enquiry was boosted by the attention to textual states, for example in the work of Lorenzo Valla on the purported Donation of Constantine.

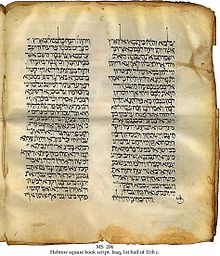

[5][page needed] Interest in applying textual criticism to the Quran has also developed after the discovery of the Sana'a manuscripts in 1972, which possibly date back to the seventh to eighth centuries.

[16] Since the mid-19th century, eclecticism, in which there is no a priori bias to a single manuscript, has been the dominant method of editing the Greek text of the New Testament (currently, the United Bible Society, 5th ed.

show evidence that particular care was taken in their composition, for example, by including alternative readings in their margins, demonstrating that more than one prior copy (exemplar) was consulted in producing the current one.

Stemmatics and copy-text editing – while both eclectic, in that they permit the editor to select readings from multiple sources – sought to reduce subjectivity by establishing one or a few witnesses presumably as being favored by "objective" criteria.

Relations between the lost intermediates are determined by the same process, placing all extant manuscripts in a family tree or stemma codicum descended from a single archetype.

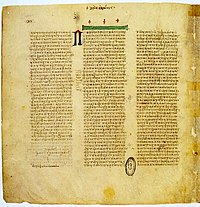

The Westcott and Hort text, which was the basis for the Revised Version of the English bible, also used the copy-text method, using the Codex Vaticanus as the base manuscript.

[44] The bibliographer Ronald B. McKerrow introduced the term copy-text in his 1904 edition of the works of Thomas Nashe, defining it as "the text used in each particular case as the basis of mine".

The French critic Joseph Bédier likewise became disenchanted with the stemmatic method, and concluded that the editor should choose the best available text, and emend it as little as possible.

[45] By 1939, in his Prolegomena for the Oxford Shakespeare, McKerrow had changed his mind about this approach, as he feared that a later edition—even if it contained authorial corrections—would "deviate more widely than the earliest print from the author's original manuscript".

[46] Anglo-American textual criticism in the last half of the 20th century came to be dominated by a landmark 1950 essay by Sir Walter W. Greg, "The Rationale of Copy-Text".

[citation needed] In his 1964 essay, "Some Principles for Scholarly Editions of Nineteenth-Century American Authors", Bowers said that "the theory of copy-text proposed by Sir Walter Greg rules supreme".

[53] Whereas Greg had limited his illustrative examples to English Renaissance drama, where his expertise lay, Bowers argued that the rationale was "the most workable editorial principle yet contrived to produce a critical text that is authoritative in the maximum of its details whether the author be Shakespeare, Dryden, Fielding, Nathaniel Hawthorne, or Stephen Crane.

"[58] Tanselle notes that, "Textual criticism ... has generally been undertaken with a view to reconstructing, as accurately as possible, the text finally intended by the author".

Bowers's approach was to preserve the stylistic and literary changes of 1896, but to revert to the 1893 readings where he believed that Crane was fulfilling the publisher's intention rather than his own.

There were, however, intermediate cases that could reasonably have been attributed to either intention, and some of Bowers's choices came under fire—both as to his judgment, and as to the wisdom of conflating readings from the two different versions of Maggie.

Though the editor may indeed give a rational account of his decision at each point on the basis of the documents, nevertheless to aim to produce the ideal text which Crane would have produced in 1896 if the publisher had left him complete freedom is to my mind just as unhistorical as the question of how the first World War or the history of the United States would have developed if Germany had not caused the USA to enter the war in 1917 by unlimited submarine combat.

"[citation needed] Between 1966 and 1975, the Center allocated more than $1.5 million in funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to various scholarly editing projects, which were required to follow the guidelines (including the structure of editorial apparatus) as Bowers had defined them.

To that latter end, Stanley R. Larson (a Rasmussen graduate student) set about applying modern text critical standards to the manuscripts and early editions of the Book of Mormon as his thesis project—which he completed in 1974.

[citation needed] In 1988, with that preliminary phase of the project completed, Professor Skousen took over as editor and head of the FARMS Critical Text of the Book of Mormon Project and proceeded to gather still scattered fragments of the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon and to have advanced photographic techniques applied to obtain fine readings from otherwise unreadable pages and fragments.

He also closely examined the Printer's Manuscript (owned by the Community of Christ—RLDS Church in Independence, Missouri) for differences in types of ink or pencil, in order to determine when and by whom they were made.

[citation needed] Thus far, Professor Skousen has published complete transcripts of the Original and Printer's Manuscripts,[75] as well as a six-volume analysis of textual variants.

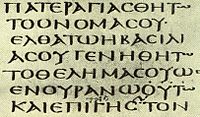

[80][81] As according to Wescott and Hort: With regard to the great bulk of the words of the New Testament, as of most other ancient writings, there is no variation or other ground of doubt, and therefore no room for textual criticism...

However, the sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, chiefly in that it makes stemmatics in many cases impossible, because many copyists used two or more different manuscripts as sources.

Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography.

[89] In an article in the 1999 Atlantic Monthly,[89] Gerd Puin is quoted as saying that: My idea is that the Koran is a kind of cocktail of texts that were not all understood even at the time of Muhammad.

[96] Marijn van Putten, who has published work on idiosyncratic orthography common to all early manuscripts of the Uthmanic text type[97] has stated and demonstrated with examples that due to a number of these same idiosyncratic spellings present in the Birmingham fragment (Mingana 1572a + Arabe 328c), it is "clearly a descendant of the Uthmanic text type" and that it is "impossible" that it is a pre-Uthmanic copy, despite its early radiocarbon dating.

Over the course of the early twenty-first century, image files became much faster and cheaper, and storage space and upload times ceased to be significant issues.