Strangeness and quark–gluon plasma

In high-energy nuclear physics, strangeness production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions is a signature and diagnostic tool of quark–gluon plasma (QGP) formation and properties.

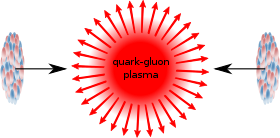

Scientists achieve this using particle collisions at extremely high speeds, where the energy released in the collision can raise the subatomic particles' energies to an exceedingly high level, sufficient for them to briefly form a tiny amount of quark–gluon plasma that can be studied in laboratory experiments for little more than the time light needs to cross the QGP fireball, thus about 10−22 s. After this brief time the hot drop of quark plasma evaporates in a process called hadronization.

[4] Preparatory work, allowing for these discoveries, was carried out at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) at the Bevalac.

Recent work by the ALICE collaboration[7] at CERN has opened a new path to study of QGP and strangeness production in very high energy pp collisions.

Therefore, any strange quarks or antiquarks observed in experiments have been "freshly" made from the kinetic energy of colliding nuclei, with gluons being the catalyst.

[10][11] An early comprehensive review of strangeness as a signature of QGP was presented by Koch, Müller and Rafelski,[12] which was recently updated.

In general, the quark-flavor composition of the plasma varies during its ultra short lifetime as new flavors of quarks such as strangeness are cooked up inside.

The up and down quarks from which normal matter is made are easily produced as quark–antiquark pairs in the hot fireball because they have small masses.

For this reason one expects that the yield of multi-strange antimatter particles produced in the presence of quark matter is enhanced compared to conventional series of reactions.

This makes it relatively easy to detect strange particles through the tracks left by their decay products.

However, considering that the light quarks are also produced in gluon fusion processes, one expects increased production of all hadrons.

The energy at RHIC is 11 times greater in the CM frame of reference compared to the earlier CERN work.

Another remarkable feature of these results, comparing CERN and STAR, is that the enhancement is of similar magnitude for the vastly different collision energies available in the reaction.

The very high precision of (strange) particle spectra and large transverse momentum coverage reported by the ALICE Collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) allows in-depth exploration of lingering challenges, which always accompany new physics, and here in particular the questions surrounding strangeness signature.

Among the most discussed challenges has been the question if the abundance of particles produced is enhanced or if the comparison base line is suppressed.

This argument can be resolved by exploring specific sensitive experimental signatures for example the ratio of double strange particles of different type, such yield of

The ALICE experiment obtained this ratio for several collision systems in a wide range of hadronization volumes as described by the total produced particle multiplicy.

Similar results were already recognized before by Petran et al.[16] Another highly praised ALICE result[7] is the observation of same strangeness enhancement, not only on AA (nucleus–nucleus) but also in pA (proton–nucleus) and pp (proton–proton) collisions when the particle production yields are presented as a function of the multiplicity, which, as noted, corresponds to the available hadronization volume.

This increase is incompatible with the hypothesis that for all reaction volumes QGP is always in chemical (yield) equilibrium of strangeness.

The fact that at extreme LHC energies we cross this boundary also in experiments with the smallest elementary collision systems, such as pp, confirms the unexpected strength of the processes leading to QGP formation.

Beyond strangeness the great advantage offered by LHC energy range is the abundant production of charm and bottom flavor.

[39][40] Looking back to the beginning of the CERN heavy ion program one sees de facto announcements of quark–gluon plasma discoveries.

The peak of emission indicates that the additionally formed antimatter particles do not originate from the colliding nuclei themselves, but from a source that moves at a speed corresponding to one-half of the rapidity of the incident nucleus that is a common center of momentum frame of reference source formed when both nuclei collide, that is, the hot quark–gluon plasma fireball.

One of the most interesting questions is if there is a threshold in reaction energy and/or volume size which needs to be exceeded in order to form a domain in which quarks can move freely.

In view of these results the objective of ongoing NA61/SHINE experiment at CERN SPS and the proposed low energy run at BNL RHIC where in particular the STAR detector can search for the onset of production of quark–gluon plasma as a function of energy in the domain where the horn maximum is seen, in order to improve the understanding of these results, and to record the behavior of other related quark–gluon plasma observables.

The theoretical work in this field today focuses on the interpretation of the overall particle production data and the derivation of the resulting properties of the bulk of quark–gluon plasma at the time of breakup.

In both cases one describes the data within the statistical thermal production model, but considerable differences in detail differentiate the nature of the source of these particles.

At yet higher LHC energies saturation of strangeness yield and binding to heavy flavor open new experimental opportunities.

Scientists studying strangeness as signature of quark gluon plasma present and discuss their results at specialized meetings.

[52][53] A more general venue is the Quark Matter conference, which last time took place from 3–9 September 2023 in Houston, USA, attracting about 800 participants.