Synapsida

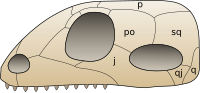

[7] The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period,[1] when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

[12][13][14] Most lineages of pelycosaur-grade synapsids were replaced by the more advanced therapsids, which evolved from sphenacodontoid pelycosaurs, at the end of the Early Permian during the so-called Olson's Extinction.

Synapsids were the largest terrestrial vertebrates in the Permian period (299 to 251 mya), rivalled only by some large pareiasaurian parareptiles such as Scutosaurus.

These therapsids rebounded as disaster taxa during the early Mesozoic, with the dicynodont Lystrosaurus making up as much as 95% of all land species at one time,[15][16] but declined again after the Smithian–Spathian boundary event with their dominant niches largely taken over by the rise of archosaurian sauropsids, first by the pseudosuchians and then by the pterosaurs and dinosaurs.

After the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs, synapsids (as mammals) rose to dominance once again during the Cenozoic.

However, this notion was disproved upon closer inspection of skeletal remains, as synapsids are differentiated from reptiles by their distinctive temporal openings.

Synapsids were subsequently considered to be a later reptilian lineage that became mammals by gradually evolving increasingly mammalian features, hence the name "mammal-like reptiles" (also known as pelycosaurs).

Although Synapsida and Therapsida include modern mammals, in practical usage, those two terms are used almost exclusively when referring to the more basal members that lie outside of Mammaliaformes.

As they evolved in synapsids, these jaw bones were reduced in size and either lost or, in the case of the articular, gradually moved into the ear, forming one of the middle ear bones: while modern mammals possess the malleus, incus and stapes, basal synapsids (like all other tetrapods) possess only a stapes.

Over time, as synapsids became more mammalian and less 'reptilian', they began to develop a secondary palate, separating the mouth and nasal cavity.

In early synapsids, a secondary palate began to form on the sides of the maxilla, still leaving the mouth and nostril connected.

The palate also began to extend back toward the throat, securing the entire mouth and creating a full palatine bone.

[35] It is currently unknown exactly when mammalian characteristics such as body hair and mammary glands first appeared, as the fossils only rarely provide direct evidence for soft tissues.

An exceptionally well-preserved skull of Estemmenosuchus, a therapsid from the Upper Permian, preserves smooth skin with what appear to be glandular depressions,[36] an animal noted as being semi-aquatic.

[37] The oldest known fossil showing unambiguous imprints of hair is the Callovian (late middle Jurassic) Castorocauda and several contemporary haramiyidans, both non-mammalian mammaliaform[38][39] (see below, however).

[40] There is evidence that some other non-mammalian cynodonts more basal than Castorocauda, such as Morganucodon, had Harderian glands, which are associated with the grooming and maintenance of fur.

[40] It is possible that fur and associated features of true warm-bloodedness did not appear until some synapsids became extremely small and nocturnal, necessitating a higher metabolism.

[41] However, Late Permian coprolites from Russia and possibly South Africa showcase that at least some synapsids did already have pre-mammalian hair in this epoch.

[42][43] Early synapsids, as far back as their known evolutionary debut in the Late Carboniferous period,[44] may have laid parchment-shelled (leathery) eggs,[45] which lacked a calcified layer, as most modern reptiles and monotremes do.

[44] According to Oftedal, early synapsids may have buried the eggs into moisture laden soil, hydrating them with contact with the moist skin, or may have carried them in a moist pouch, similar to that of monotremes (echidnas carry their eggs and offspring via a temporary pouch[47][48]), though this would limit the mobility of the parent.

Cynodonts were almost certainly able to produce this, which allowed a progressive decline of yolk mass and thus egg size, resulting in increasingly altricial hatchlings as milk became the primary source of nutrition, which is all evidenced by the small body size, the presence of epipubic bones, and limited tooth replacement in advanced cynodonts, as well as in mammaliaforms.

[44][45] Aerial locomotion first began in non-mammalian haramiyidan cynodonts, with Arboroharamiya, Xianshou, Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon bearing exquisitely preserved, fur-covered wing membranes that stretch across the limbs and tail.

The presence of fibrolamellar, a specialised type of bone that can grow quickly while maintaining a stable structure, shows that Ophiacodon would have used its high internal body temperature to fuel a fast growth comparable to modern endotherms.

Synapsid adaptive radiations have generally occurred after extinction events that depleted the biosphere and left vacant niches open to be filled by newly evolved taxa.

The second were specialised, beaked herbivores known as dicynodonts (such as the Kannemeyeriidae), which contained some members that reached large size (up to a tonne or more).

And finally there were the increasingly mammal-like carnivorous, herbivorous, and insectivorous cynodonts, including the eucynodonts from the Olenekian age, an early representative of which was Cynognathus.

Dicynodonts are generally thought to have become extinct near the end of the Triassic period, but there was evidence this group survived, in the form of six fragments of fossil bone that were found in Cretaceous rocks of Queensland, Australia.

Below is a cladogram of the most commonly accepted phylogeny of synapsids, showing a long stem lineage including Mammalia and successively more basal clades such as Theriodontia, Therapsida and Sphenacodontia:[59][60] †Caseasauria †Varanopidae †Ophiacodontidae †Edaphosauridae †Sphenacodontidae †Biarmosuchia †Dinocephalia †Anomodontia †Gorgonopsia †Therocephalia † Cynognathia Mammalia Most uncertainty in the phylogeny of synapsids lies among the earliest members of the group, including forms traditionally placed within Pelycosauria.

As one of the earliest phylogenetic analyses, Brinkman & Eberth (1983) placed the family Varanopidae with Caseasauria as the most basal offshoot of the synapsid lineage.

Stereophallodon ciscoensis Archaeovenator hamiltonensis Pyozia mesenensis Mycterosaurus longiceps ?Elliotsmithia longiceps (BP/1/5678) Heleosaurus scholtzi Mesenosaurus romeri Varanops brevirostris Watongia meieri Varanodon agilis Ruthiromia elcobriensis Aerosaurus wellesi Aerosaurus greenleorum Eothyris parkeyi Oedaleops campi Oromycter dolesorum Casea broilii Trichasaurus texensis Euromycter rutenus (="Casea" rutena) Ennatosaurus tecton Angelosaurus romeri Cotylorhynchus romeri Cotylorhynchus bransoni Cotylorhynchus hancocki Ianthodon schultzei Ianthasaurus hardestiorum Glaucosaurus megalops Lupeosaurus kayi Edaphosaurus boanerges Edaphosaurus novomexicanus Haptodus garnettensis Pantelosaurus saxonicus Raranimus dashankouensis Biarmosuchus tener Biseridens qilianicus Titanophoneus potens Cutleria wilmarthi Secodontosaurus obtusidens Cryptovenator hirschbergeri Dimetrodon spp.