Technology during World War II

This included the exfiltration of Niels Bohr from German-occupied Denmark to Britain in 1943; the sabotage of Norwegian heavy water production; and the bombing of Peenemunde.

As in World War I, the French generals expected that armour would mostly serve to help infantry break the static trench lines and storm machine gun nests.

The laboratory of Ludwig Prandtl at University of Göttingen was the world center of aerodynamics and fluid dynamics in general, until its dispersal after the Allied victory.

[5][6][7][8] The origin of the cooperation stemmed from a 1940 visit by the Aeronautical Research Committee chairman Henry Tizard that arranged to transfer U.K. military technology to the U.S. in case of the successful invasion of the U.K. that Hitler was planning as Operation Sea Lion.

Superior German aircraft, aided by ongoing introduction of design and technology innovations, allowed the German armies to overrun Western Europe with great speed in 1940, assisted by lack of Allied aircraft, which in any case lagged in design and technical development during the slump in research investment after the Great Depression.

Subsequently, the Luftwaffe was able to achieve air superiority over France in 1940, giving the German military an immense advantage in terms of reconnaissance and intelligence.

German aircraft rapidly achieved air superiority over France in early 1940, allowing the Luftwaffe to begin a campaign of strategic bombing against British cities.

Utilizing France's airfields near the English Channel the Germans were able to launch raids on London and other cities during the Blitz, with varying degrees of success.

Air warfare of World War II began with the bombing of Shanghai by the Imperial Japanese Navy on January 28, 1932, and August 1937.

The Spanish Civil War had proved that tactical dive-bombing using Stukas was a very efficient way of destroying enemy troops concentrations, and so resources and money had been devoted to the development of smaller bomber craft.

As a result, the Luftwaffe was forced to attack London in 1940 with heavily overloaded Heinkel and Dornier medium bombers, and even with the unsuitable Junkers Ju 87.

As a result, German bombers were shot down in large numbers, and were unable to inflict enough damage on cities and military-industrial targets to force Britain out of the war in 1940 or to prepare for the planned invasion.

British long-range bomber planes such as the Short Stirling had been designed before 1939 for strategic flights and given a large armament, but their technology still suffered from numerous flaws.

However, despite their seeming technological edge, German jets were often hampered by technical problems, such as short engine lives, with the Me 262 having an estimated operating life of just ten hours before failing.

The first and only operational Allied jet fighter of the war, the British Gloster Meteor, saw combat against German V-1 flying bombs[11] but did not significantly distinguish from top-line, late-war piston-driven aircraft.

The Treaty of Versailles had imposed severe restrictions upon Germany constructing vehicles for military purposes, and so throughout the 1920s and 1930s, German arms manufacturers and the Wehrmacht had begun secretly developing tanks.

As these vehicles were produced in secret, their technical specifications and battlefield potentials were largely unknown to the European Allies until the war actually began.

Driven by the desperate necessity of keeping Britain supplied, technologies for the detection and destruction of submarines was advanced at high priority.

Earlier renditions that hinted at this idea were that of the employment of the Browning Automatic Rifle and 1916 Fedorov Avtomat in a walking fire tactic in which men would advance on the enemy position showering it with a hail of lead.

It spurred post-war development on both sides of the upcoming Cold War and is still used by some armies to this day including the German Bundeswehr's MG 3.

[13] In Britain, Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, working under Mark Oliphant at the University of Birmingham, made a breakthrough investigating the critical mass of uranium-235 in June 1939.

[15] A directorate known as Tube Alloys was established in the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research under Wallace Akers to pursue the development of an atomic bomb.

[16] In July 1940, Britain offered to give the United States access to its scientific research,[17] and the Tizard Mission's John Cockcroft briefed American scientists on British developments.

[18] Oliphant flew to the United States in late August 1941 and spoke persuasively to Ernest O. Lawrence and other key American physicists about the feasibility and potential power of an atomic bomb.

Other key figures in the German project included Manfred von Ardenne, Walther Bothe, Kurt Diebner and Otto Hahn.

Germany started the war ahead in some aspects of radar, but lost ground to research and development of the cavity magnetron in Britain and to later work at the "Radiation Laboratory" of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

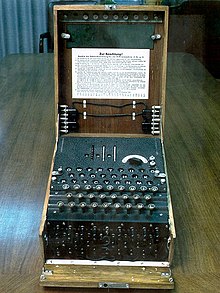

The Germans in turn widely relied on their own variants of the Enigma coding machine for encrypting operations communications, and Lorenz cipher for strategic messages.

The meticulous work of code breakers based at Britain's Bletchley Park played a crucial role in the final defeat of Germany.

The first of the so-called Vergeltungswaffen series designed for terror bombing of London, the V-1 was fired from launch facilities along the French (Pas-de-Calais) and Dutch coasts.

[47][48] Advances in the treatment of burns, including the use of skin grafts, mass immunization for tetanus and improvements in gas masks also took place during the war.