Science and technology of the Song dynasty

Shen Kuo (1031–1095), author of the Dream Pool Essays, is a prime example, an inventor and pioneering figure who introduced many new advances in Chinese astronomy and mathematics, establishing the concept of true north in the first known experiments with the magnetic compass.

Song era antiquarians such as Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) and Shen Kuo dabbled in the nascent field of archaeology and epigraphy, inspecting ancient bronzewares and inscriptions to understand the past.

[7][8] One of Shen's greatest achievements, aided by Wei Pu, was correcting the lunar error by diligently recording and plotting the moon's orbital path three times a night over a period of five years.

[9] Su Song, one of Shen Kuo's political rivals at court, wrote a famous pharmaceutical treatise in 1070 known as the Bencao Tujing, which included related subjects on botany, zoology, metallurgy, and mineralogy.

[18] The cases of these two men display the eagerness of the Song in drafting highly skilled officials who were knowledgeable in the various sciences which could ultimately benefit the administration, the military, the economy, and the people.

Intellectual men of letters like the versatile Shen Kuo dabbled in subjects as diverse as mathematics, geography, geology, economics, engineering, medicine, art criticism, archaeology, military strategy, and diplomacy, among others.

[20][21] On a court mission to inspect a frontier region, Shen Kuo once made a raised-relief map of wood and glue-soaked sawdust to show the mountains, roads, rivers, and passes to other officials.

[20] Shen Kuo is also noted for improving the designs of the inflow clepsydra clock for a more efficient higher-order interpolation, the armillary sphere, the gnomon, and the astronomical sighting tube; increasing its width for better observation of the pole star and other celestial bodies.

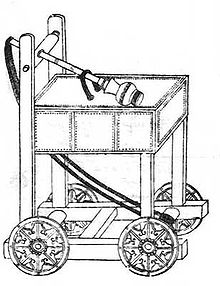

[24] However, the concluding paragraph provides description at the end of how the device ultimately functions: When the middle horizontal wheel has made 1 revolution, the carriage will have gone 1 li and the wooden figure in the lower story will strike the drum.

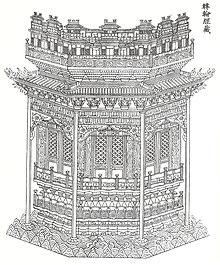

[32] A later Muslim traveler Shah Rukh (son of the Turco-Mongol warlord Timur) came to Ming dynasty China in 1420 during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, and described a revolving repository in Ganzhou of Gansu province that he called a 'kiosque': In another temple there is an octagonal kiosque, having from the top to the bottom fifteen stories.

The flamethrower found its origins in Byzantine-era Greece, employing Greek fire (a chemically complex, highly flammable petrol fluid) in a device with a siphon hose by the 7th century.

[50] The Chinese applied the use of double-piston bellows to pump petrol out of a single cylinder (with an upstroke and downstroke), lit at the end by a slow-burning gunpowder match to fire a continuous stream of flame.

[53] These 'fire-lances' were widespread in use by the early 12th century, featuring hollowed bamboo poles as tubes to fire sand particles (to blind and choke), lead pellets, bits of sharp metal and pottery shards, and finally large gunpowder-propelled arrows and rocket weaponry.

Written later by Jiao Yu in his Huolongjing (mid 14th century), this manuscript recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the 'flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor' (fei yun pi-li pao).

[68] In his day, the Chinese became concerned with a barge traffic problem at the Shanyang Yundao section of the Grand Canal, as ships often became wrecked while passing the double slipways and were robbed of the tax grain by local bandits.

Their cargoes of imperial tax-grain were heavy, and as they were passing over they often came to grief and were damaged or wrecked, with loss of the grain and peculation by a cabal of the workers in league with local bandits hidden nearby.

[70] Shen Kuo wrote that the establishment of pound lock gates at Zhenzhou (presumably Kuozhou along the Yangtze) during the Tian Sheng reign period (1023–1031) freed up the use of five hundred working laborers at the canal each year, amounting to the saving of up to 1,250,000 strings of cash annually.

This is best represented in the Dongpo Zhilin of the governmental official and famous poet Su Shi (1037–1101), who wrote about two decades before Shen Kuo in 1060: Several years ago the government built sluice gates for the silt fertilization method, though many people disagreed with the plan.

In his Dream Pool Essays (1088), Shen Kuo wrote: At the beginning of the dynasty (c. 965) the two Zhe provinces (now Zhejiang and southern Jiangsu) presented (to the throne) two dragon ships each more than (60.00 m/200 ft) in length.

[77] This was a simple iron or steel needle that was heated, cooled, and placed in a bowl of water, producing the effect of weak magnetization, although its use was described only for navigation on land and not at sea.

[78] In addition, Zhu Yu wrote of watertight bulkhead compartments in the hulls of ships to prevent sinking if damaged, the for-and-aft lug, taut mat sails, and the practice of beating-to-windward.

The Commander of such a vessel is a great Emir; when he lands, the archers and the Ethiops (i.e. black slaves, yet in China these men-at-arms would have most likely been Malays) march before him bearing javelins and swords, with drums beating and trumpets blowing.

[88] In 1135 the famous general Yue Fei (1103–1142) ambushed a force of rebels under Yang Yao, entangling their paddle wheel craft by filling a lake with floating weeds and rotting logs, thus allowing them to board their ships and gain a strategic victory.

[95][98] However, by the end of the 11th century the Chinese discovered that using bituminous coke could replace the role of charcoal, hence many acres of forested land and prime timber in northern China were spared by the steel and iron industry with this switch of resources to coal.

For example, the poet and statesman Su Shi wrote a memorial to the throne in 1078 that specified 36 ironwork smelters, each employing a work force of several hundred people, in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture (under his governance while he administered Xuzhou).

[104] In 31, the Han dynasty governmental prefect and engineer Du Shi (d. 38) employed the use of horizontal waterwheels and a complex mechanical gear system to operate the large bellows that heated the blast furnace in smelting cast iron.

European travelers to China in the late 16th century were surprised to find large single-wheel passenger and cargo wheelbarrows not only pulled by mule or horse, but also mounted with ship-like masts and sails to help push them along by the wind.

[117] During the early half of the Song dynasty (960–1279), the study of archaeology developed out of the antiquarian interests of the educated gentry and their desire to revive the use of ancient vessels in state rituals and ceremonies.

If the latter determination was made a prefectural official would investigate, draw up an inquest that included sketches of potential injuries on the deceased body, and have it signed by witnesses for presentation in a court of law.

[125] Details of these efforts are preserved in written accounts such as the Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified by the judge and physician Song Ci (1186–1249), whose work documents various types of death (strangulation, drowning, poison, blows, etc.)